-

Parker J. Palmer "On the Brink of Everything" | Episode Transcript

Karen Pascal: Hello, I’m Karen Pascal, the executive director of the Henri Nouwen Society, and I want to welcome you to a new episode of Henri Nouwen, Now and Then. Today, I’m delighted to introduce you to a man who was a good friend of Henri Nouwen’s, Parker Palmer. Krista Tippett, host of On Being on NPR, says of Parker Palmer: “He has the spirit of a poet and the stature of a prophet.” Parker Palmer is a well-known writer, teacher and activist, founder and Senior Partner Emeritus of the Center for Courage and Renewal. Parker has also authored 10 books, including Let Your Life Speak, The Courage to Teach and Healing the Heart of Democracy.

Parker Palmer, it’s a delight to have the opportunity to talk with you today on Now and Then. I want to tell you, I just loved your book. It was just a treasure. Thank you, thank you, thank you for sending it. And as I read, I got three chapters in and I was suddenly ordering copies for all the friends that I wanted to have it. You’re a beautiful writer.

Parker Palmer: Thank you.

Karen Pascal: Well, you’re welcome. Yeah, it was a lovely, lovely treat, and a joy for me today to talk with you about it, because I think it’s something that our Nouwen audience will thoroughly enjoy. To be quite honest with you, I think it’s a treasure. Now, what led you . . . let’s go back a little bit, so that the audience has some feeling of what’s this about. What led you to write On the Brink of Everything?

Parker Palmer: Well, thanks, Karen. Great question. I’ve been thinking about mortality, I think probably since I was 18 years old. Not in a morbid way, but I remember in my twenties reading the Rule of Benedict, where St. Benedict says, “Daily, keep your death before your eyes.” I think a lot of 20-year-olds would regard that as morbid advice, but I pretty quickly saw if you could do that, it would be very life-giving advice, because you would appreciate each and every gift of life. So, the topic is kind of second nature to me. And as I got into my late sixties, early seventies – I’m now 81 – I started writing about it. Not self-consciously, not as a topic that I sort of took on intentionally, but just because my writing has always come from what’s going on inside of me.

And I was writing at [the] time for Krista Tippett’s program, On Being, which has a wonderful website on the public radio website. And I did a column a week for about five years, and a number of those columns were about aging. So, I was talking with my editor one day, when I was in my late seventies. And she said, “You know, Parker, I know you don’t feel you have the energy for another marathon book, but you might want to pull some of your short essays together and make a book out of them.” And I said, “Well, that’s a keen idea, but a book has to be about something. And I’m not clear that I’ve been writing about something.” And she paused; I remember there was a little silence on the phone. And she said, “Do you ever read your own writing?”

And I said, “No, why should I? I have to write it; why should I read it?” And she said, “Well, let me clue you in: You have been writing about something and that something is aging. And I think it would make a wonderful book.”

So, I took her advice. She’s a trustworthy editor of many years, Cheryl Fullerton, and pulled together some of those On Being pieces and other things that I had written, and started looking at how they might be woven together and how I might write some new material to fill in the gaps. And that’s how On the Brink of Everything came into being.

Karen Pascal: You know, what I found charming was you mentioned the editor, but you also, in your book, mentioned that you run your books by your wife. And she asks the question, “Was it said beautifully?” And that was one of the things that really struck me about the book. It was said beautifully on every page. And I also found . . . Let’s face it: There’s a lot of reality-checking when you look at age; there’s a lot of weight to it. And I found the book sprinkled with wit, which makes it easier for the truth to go down. And you need laughter to open you up to receive truth. So, I find your writing has that kind of a neat balance between those elements. It’s beautiful. The poetry is beautiful. That was a big surprise for me. Not that I was surprised that your poetry was beautiful, but just how much it’s a part of your life. And I felt like the book reflected the way you got to where you are today. I mean, clearly nature has played a very important role in your life.

Parker Palmer: Yes, absolutely. And thank you for those kind words. Yes. Nature, actually, I think as an important factor in my life, came along in midlife – probably I was in my forties. I grew up in the Chicago suburbs and I really did not grow up immersed in nature. But in my mid-forties, my wife, who’s very immersed in nature, started dragging me out into the woods and the wilderness and the mountains and the deserts. And I just loved it. I loved it very much, and started taking 10-day, silent, solitary retreats in the deserts of New Mexico, for example. We started spending anywhere from two to four weeks, every late summer, early fall in the Boundary Waters of northern Minnesota, which of course is right on the Canadian border.

And on the other side of the border is Quetico, these amazing millions and millions of acres of wilderness with no motors allowed in big sections of it. And so, nature became a source of inspiration, a source of encouragement, a source of renewal for me. And I think, especially with age and the kind of ruination that’s always going on in our world that seems to have accelerated in recent times, nature carries some very important lessons about what I’d call resurrection. In the Boundary Waters, for example, we have been up there before and after immense blowdowns – derechos, they call them – that take down just millions of trees at a time. Or fires that then come, because there’s so much tinder out there waiting to burn. And as you keep returning to that place, you see the way nature reclaims itself after those times of devastation. And the times of devastation actually turn out to be seed beds, fertilizer, humus for the regrowth of new species, new flowers, new trees, and so forth. So, I get so much from nature that it’s really hard to wrap my words around it.

Karen Pascal: When you speak of that devastating wind that just changes the whole surface of a beautiful forest, it reminds me of what we’re living with right now. We’ve seen something so change our world so instantly it’s incredible, isn’t it? Will it be the seed bed for something new? Obviously, I guess it will – we hope it will.

Parker Palmer: Yeah, we certainly hope it will. And of course, the realization of that hope depends on us. I have a feeling in this country, since 2016 and we elected a new president who is a very distressing presence and set of policies and practices, distressing policies and practices for many of us, obviously not for all of us, I think many who simply find him and his ideas and the way he does his work unacceptable. We have been saying to ourselves for the past three to four years, “This is an opportunity for transformation.” And many of us have been reminding ourselves, if we’re of a religious bent, as I certainly am, that the word “apocalypse” in its original Greek root means “revelation” – to uncover, to reveal. And if these feel like apocalyptic times, the hope is that something is being revealed. And what’s being revealed has to do with the fact that we’ve not only built on sand, we’ve built on quicksand. And in the United States of America, at least, that involves almost every aspect of our country and our culture.

I mean, our economy, for example, is rooted in the horrific, inhumane, evil practice of enslaving human beings and getting them to do your work for free and not letting them profit from their own labors. And a lot of folks are thinking very hard about the fact that the racism that we deal with in every generation is part of the DNA of this society, and will probably never leave us. But it has to be mitigated. And I think strenuous efforts are going on in that direction. I think it’s a fair analogy with the genetic makeup of a human being, to say that the genetic makeup of the nation needs some gene-splicing, or some gene therapy. The underlying condition may persist, but its manifestations can be considerably and must be considerably dialed down.

So, I’m one who continues to hope that revelations will also emerge from the coronavirus epidemic. If nothing else, in this country, we have another chance to realize that America First is an utterly nonsensical and dare I say, a stupid way of looking at governing this nation or looking at being a citizen in this world, where everything is so profoundly interconnected with everything else. I wrote a piece the other day in which I said, “Are we getting the lesson about global interconnection?” I said financial markets have gotten that lesson. Even viruses know this is the case. How about us waking up and smelling the coffee?

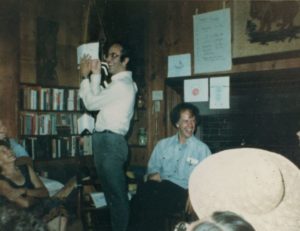

Karen Pascal: Absolutely. Well, one of the things I’ve loved about discovering you through this book was really the fact that your activism and your faith come together in a really special way. I’m going to go back a little bit to where I first met you. You weren’t there, but you were there in a picture. I was doing a documentary on Henri Nouwen and I was finding the pictures that could piece together the story of his life. And clearly, because I didn’t know Henri other than having met him to do a little bit of television with him, I didn’t know him the way his friends and his colleagues and his family knew him. So, as I went through pictures, I came across this one picture that just glowed with life. And it’s you and Henri, and it looked like a place I wanted to be. There was laughter in it; there was, I don’t know, there was this energy in that picture that made me ask, “Who is this person and how does he relate to Henri Nouwen?” Tell me, how did you relate to Henri Nouwen? I think it’s back in your, maybe your thirties? Is that where you are? I’m not quite sure, but I just saw an energy in this relationship and I’m curious, what was it and how has Henri Nouwen kind of been an impact or an influence to you?

Parker Palmer: Well, thank you. What a lovely story. And if you ever have a chance to copy that picture and send it to me, I’d love to see it. I’m not sure which one it is. But so, yes, it was in my late thirties, as best I can reconstruct it. And I was living in an intentional Quaker community called Pendle Hill, which is near Philadelphia, and has been there since 1930 as a place where Quaker faith and practice is put into action, and what, at the time, was an intentional community and adult study center of about 80 people. It was a kind of Quaker ashram or monastery or kibbutz or commune. But unlike a monastery, we had married people and children and families, the whole nine yards. And after a year there as an adult student who thought he was just taking a break from my work as a community organizer in Washington, DC, I found myself quite by surprise becoming Dean of Studies, and I stayed on there for another 10 years.

Henri and I met during the second half of my thirties – I was maybe 38 or 39 or so – because the Lilly endowment, a big foundation in this country, had gotten into the business of making grants for projects on spirituality, which was a relatively new field at the time, especially in seminaries, which were a little leery of spirituality. And they brought together a group of, I’m going to say eight or 10 people, at a hotel in New York City to help them evaluate the proposals that were pouring in for these spirituality grants. They had a lot of money to give away and they wanted to give it away well. Henri was one of those people, I was one of those people, and we found ourselves, I think, sitting next to each other at a table where we were all reading proposals. We struck up a friendship just talking about these things, and that friendship carried on well after the three days – I think it was three days – that we spent sort of cloistered in New York, working on this Lilly endowment assignment.

Henri, of course, was intrigued with Pendle Hill. He was at Yale Divinity School at the time. And he loved the idea of communal living that was rooted in Quaker worship every morning. It was very different from the worship style that he was accustomed to, of course, but it’s very interesting that historically, Quakers and Catholics have more in common than either has with mainline Protestants, because in both forms of worship, both the Eucharist and the Quaker silent meeting, the theological belief is that the living Christ is present.

And while he and I didn’t talk about that a lot, I think there was a sort of shared sensibility about some of the deep roots that wouldn’t be normally be evident to folks, because Catholicism, of course, is very hierarchical and Quakerism don’t even have priests or pastors or clergy; it’s a profoundly communal form of Christianity. But Henri would visit my family and me at Pendle Hill. He was great with kids. I have some favorite memories of Henri at the dinner table. I have a son named Todd who at the time was maybe eight years old. And he wanted to be a writer, too. And he was fascinated with all the books Henri had already written. And one night at the dinner table, Todd piped up and said, “Henri, I’ve figured out how you write so many books.”

And Henri said, “Oh, really? Tell me.”

And of course, I was intrigued, too. What’s going to come out of this kid’s mouth, because he often took me by surprise. And Todd said, “Well, the way you write so many books is large print, wide margins and a lot of pictures.”

And there’s some truth to that, you know? So, Henri laughed so hard, and we did a lot of laughing in our time together. I wouldn’t know what to do without laughter in my life. I mean, I once wrote something like, “the spiritual bread of life gives you a belly ache, if it isn’t leavened with humor.” It’s just possible, I think it’s too often the case that religious people are or become grim people, and you know, Henri wasn’t that way at all. So, I think a really remarkable piece of our journey together was in the fact that we decided at one point that, for two years, during the academic year, Henri would come down from Yale Divinity School, where he had a lot more freedom than I did, as a member of an intentional community.

He’d come down to Pendle Hill from Yale. We would spend a whole day working together, talking together first, about education, community, and spirituality, because those were things that I was very engaged with and Henri was, too. Sometimes, he brought with him – very often, he brought with him John Mogabgab, who was his assistant at Yale, and who became a wonderful friend of mine as well. Sadly, the late John Mogabgab. But we would spend a whole day together talking and then we would commit to meeting again two weeks later. And before we met again, we would have written a three- or four-page paper reflecting what we got out of the previous conversation. We’d mail those to each other. This is in the days before email, boys and girls, and we’d use that as the springboard for our next conversation. So, it was a really remarkable kind of colleagueship. And I think at one point we may have entertained the idea of writing a book together, but we never did that. Instead, those notes became sort of the compost for writing that each one of us did in our own way and under our own names over the next several years. So, I’ve always treasured that experience.

Karen Pascal: What a great kind of friendship! I didn’t know that’s how it worked, but I’d love to go into the archives and see if I could find those actual letters that went back and forth between you. One of the things we’ve been very grateful for with the Henri Nouwen archives, a lot of people have given back their letters because it was an era of letter writing. And Henri was a good letter writer. He was somebody who was very committed to that as part of his ministry. It’s interesting, Parker, as I read your book, I found myself poring over the pages, looking for hints of Henri. I confess that’s kind of weak on my part, but you know, what I found was I found at some point you said, “to share the journey toward broken wholeness.”

Broken wholeness: That’s a language Henri understood. Broken wholeness. There are so many good things in this book. Oh, as I said, I just love it. And I have loads of questions I want to ask you about it. But I want to encourage people: If you’re listening to this conversation, I’m so delighted to finally have a chance to talk with Parker, but I also really want to encourage you. Parker’s written 10 books and they’re wonderful books. I met him before in his books, but this latest one, I want to encourage everyone that’s listening: On the Brink of Everything is worth having. And it’s not just for seniors, honestly, it’s not. It’s just a wealth of thoughtful things about how to do life, I think.

One of the things that I came across here was you distinguish between work and vocation. And I’d like to ask you, Parker, what was your calling? What was your vocation? You say, “jobs by which we make our living, the callings or vocations by which we make meaning.” And I was curious if you could just tell us your calling.

Parker Palmer: That’s been an important distinction for me, because I’ve had a very irregular career as measured by conventional standards. I went to all the trouble of getting a PhD at Berkeley when I was in my twenties, a PhD in sociology, thinking I would go into academic life. And by the time I got it, I was both weary of academic life and also felt compelled and called by what was going on in the country at the time, which was leaders being assassinated, Vietnam rising, cities burning because of racism. So, I went to Washington DC and became a community organizer. And that would take longer than we have to lay out the whole occupational journey, which has taken me through many zigs and zags over my 81 years.

But I couldn’t possibly, you know, if I just listed the job titles or descriptions, I couldn’t really find a red thread in there. But vocation for me is the red thread. And I think while it took me a long time to figure it out, I think my fundamental vocation in life has been, my calling in life has been to be a learner and a teacher, which are two words that I think necessarily go together. I remember, for example, I mean, my first clue to this was that when I left Berkeley with PhD in hand and became a community organizer, for several months, I grieved what I saw as the loss of my opportunity to teach, because I had teaching very narrowly defined as something one does in a classroom with students who are enrolled for a degree.

And of course, what I learned eventually, pretty obvious, except when you’re in the midst of your own confusion or sense of loss. What I learned was that as a community organizer, I was still a teacher and that teaching was basically what I did. Teaching rooted in learning about the community and listening to people and trying to see the needs of the world as manifested in this particular place and trying to respond to them as best I knew how. And very often, the best response I could make was to teach what I was learning and then, you know, learn what I was teaching, because people needed to understand in order to move ahead with the problems that vexed that community at that time. So, I think whatever I’ve done partakes in that vocation of learning/teaching or teaching/learning. Certainly, writing a book is that way for me.

So, that’s a case in which you don’t know who you’re standing up in front of and speaking. And that in itself leads to some really interesting, I think, insights into what teaching is all about. And I’ll just share one, of what I think good teaching is all about. With each of the 10 books I’ve published, the first people you talk to at the publisher, once the manuscript is approved, are the promotional people, the sales people. And their first question, really, their only question back in the day, was, “So who’s this book for?” And my answer has been very consistent over the years. From my first book at age 40 to my most recent book at age 80, my answer has been, “Well, it’s for whoever buys it.” And the promo people have always looked at me unhappily and said, “Well, that really doesn’t help us. Parker. I mean, come on. What we mean is, is it for clergy? Is it for faculty? You know, is it for dog catchers? Who’s it for? We’ve got to aim it at somebody.”

And I’ve always said, “Look, I really, really cannot tell you who it’s for. Because with every book I’ve written, I’ve been surprised, totally surprised by the lines it has crossed. And by the people who’ve been drawn to it, who are people that I could not have imagined being interested in in this.”

I mean, you know, I recently had a visit from a peacemaker who regularly goes into South Sudan, which is a place of ongoing genocide. And he visited me because his work was partly inspired by one of my books. Well, I don’t have the courage to go into South Sudan. I have no idea where a person of his goodwill and conviction, commitment and courage comes from, but somehow, the magic happened and the book turned out to be for him.

So, I’ve said to the promo people at the publisher, “I can’t possibly tell you who the book is for. What I can tell you, however, is where the book comes from.” And what I try to do is to write from the deepest part of myself that I have access to, around whatever subject it is that I’ve tackled, whether it’s democracy or teaching or aging or religious community in general. And knowing that if I do that, I mean, I’m now totally confident that if I do that, the book will reach a similar deep spot in whoever happens across it. And there’s no way in the world that a promotional campaign can be aimed at the human soul. Just get it out there, see what happens, scatter your seeds. And you know, sometimes they fall on rocky soil, but I’ve been lucky in that many of them have many of those seeds have fallen on fertile, fertile ground. So, that’s my vocation, I think.

Karen Pascal: Oh, that’s neat. It’s funny, because for me, I found Henri Nouwen because at the time I was doing a television program and I would ask people who inspired me, “Who inspires you? Who are you reading?” And Henri’s name kept coming up. And then I think that’s how I found you, Parker. I think I found you because you find the ones that are kindred spirits, that you go, “I like what they’re talking about.” And in a way, my defenses don’t go up when I’m reading them; they open me up to receive from them. So, I feel honored to be able to talk with you today.

And at the same time, I sort of want to say to people, you know, the spiritual conversations of the day, the current conversations of the day are vital, because the circumstances of our lives are so vital right now. We’re all trying to find our footing in the midst of it. And I encourage you to read the kind of voices, the kind of things that I see coming through from you in this book. It’s really full. And one of the things that I discovered, I felt as I read it, it’s everyone that I know that’s a writer needs to read this book, because you’re very honest about that process in your life, about the struggle and the reality. You call yourself “the accidental author,” is that it? And you claim you were “born baffled.” I don’t know what else, you know, I just love it. But I find in it that level of truth in it that just of resonates at a place where you speak to hearts. And in honesty, I really, really needed to hear what you could say about what happened to America in 2016, because the face of America changed so dramatically in terms of being this, to me, a leader on certain fronts, and suddenly being a leader in a different sort of a way.

And then we kind of discovered, well, wait a second, the whole world is kind of in a spin that’s going around that says disruption, et cetera, is okay. I found what you had to say about that very, very helpful.

Parker Palmer: Well, thank you. Thank you, Karen. Those words mean a lot to me. And let me just say a couple things about that, one of which links to back to Henri. You know, Henri was a few years older than I am. I’m not exactly sure how many, but probably five or six, something of that order. And as almost an age mate, he really became a mentor and sponsor for me. So, the first book I ever did, The Promise of Paradox, in 1979 or 80, somewhere in there, was this accidental book. I tell the story in On the Brink of Everything, about why it was an accidental book. It truly was. And I told Henri about it as it was taking shape. And he said, “Well, let me take a look at it.”

He did. And he very graciously said, “I want to write a foreword for this book.”

And I was a totally unknown quantity at the time, but Henri’s writing was already pretty well established and he was gaining a big audience. And so having his name on the cover, on the jacket and having his foreword – a very generous foreword – in the book really made a huge difference in terms of launching my writing career. And I think the deeper things that I got from Henri, one of them had to do with being vulnerable about your life experience in writing. I’m not sure everybody who reads Henri realizes that, oh, the prayers that he writes or the human struggles that he writes about aren’t just platonic forms or archetypes that he made up, or that he saw as part of the human condition. They were his struggles and his fears and his hopes.

And I was inclined in that direction, because I don’t like being in the world dishonestly, but you know, one of the things you get with a graduate education or a higher education of any sort is a sort of tendency to cover up, to hide out behind ideas. And Henri’s mentoring around that, we never talked about it, but he mentored just by being who he was and writing as he did; it was very important to me.

And then I just, secondly, want to say that there’s so many dimensions to what happened in this country in 2016 and, as you say, what’s going on around the world. But obviously, I think, for thoughtful people, one of the big dimensions is so many people are being conquered by their fears. When you lead with fear in a world like ours, it just never has a good outcome. In fact, one of its major outcomes, historically, has been fascism, and I’m not one who’s shy about using that word, even though I take some flak for it. But eight months before the 2016 election and before the surprise happened here and we elected this new president, I wrote an article for that On Being website that was titled, Will Fascism Trump Democracy? because some of us could already see that the candidate who became president was drawing on the fascist playbook, or at the very least, on an authoritarian playbook – at least in one key regard. And that is identifying a problem that vexes a lot of people, like economic inequality in this country. Secondly, blaming that problem on a scapegoat, who actually has nothing to do with the problem. In our case, of course, it was people coming across the border, either as immigrants from Mexico or as asylum-seekers from Central America, and persuading a lot of people that this was all their fault, you know, that they’re taking jobs, which frankly no American wants, and doing it cheap.

And if we could just keep them out of the country, and I’m quoting him now, this is not the truth, but all the crime and blah, blah, blah that they bring with them, then that problem would be solved. And then the third step in the fascist playbook, having identified the problem and blamed it on a scapegoat, is to promise folks that you’ll eliminate the scapegoat, one way or another. That was Hitler’s playbook with the rise of the Third Reich. And that’s been the playbook in this country, and it’s the playbook around the world.

Yes, there are legitimate problems with immigration. We need better immigration policies, but we do not need the draconian, murderous measures that make us less than human in dealing with these problems. And the challenge for all of us now alive and for the next generation is going to be, in my country, to practice resuscitation on the Statue of Liberty and to bring this country back to its deepest heritage of humanitarianism, generosity and open, welcome arms to the diversity that enriches all of us.

Karen Pascal: Well said! Well, well said! We are at a critical point. And I look forward to seeing how, I guess, in a way it sounds terrible to say, but I look forward to seeing how this is going to play itself out in the next months, the next year. I trust that all of us will be able to do our part in what that takes.

There was one last thing I’m going to ask you about: you’re “one mean Quaker.” And I thought it was, I love the phrase. I just love the phrase. Obviously, you’re passionate about the things that you’re passionate about, but you’re also committed to peacemaking. And the question that seems naturally to flow out of that is, does anger have a role to play in the life of someone who aspires to nonviolence?

Parker Palmer: Yeah. And as you know, Karen, it’s a question I pursue in the book, and my answer, of course, is yes. You know, I’m troubled by versions of Christianity that seem to say that if you’re a Christian, you can never get mad. I think that’s really in stark contrast to the biblical roots of Christianity and Judaism, where we have, for example, the Psalms that make no bones about the anger of the Psalmist. I remember being a little shocked years ago when I first heard a psalm read that contained the line, “Smash their teeth, O Lord, smash the teeth of my enemies.”

And I think I even used that in the book by saying, well, you know, I’m not going to do that personally. I don’t think any of us should smash anyone’s teeth, but I’d be glad for God to do it, because then it would be harder for some of these people to talk and we might get free dental insurance out of it, you know, which we don’t have in the United States.

But I think the question about anger is not whether it’s okay; it’s definitely okay to be angry. The question is, do I have ways of treating it as an energy or holding it as an energy that can be ridden toward good destinations rather than bad destinations? And I think that, you know, such ways and means are available. I think there’s a lot of examples in history of anger motivating positive, life-giving, constructive action. And I think it’s what anyone who’s angry about these fundamental violations of human identity and integrity, and indeed human sacredness, needs to be looking for today. So, to me, it’s an ongoing spiritual quest, an ongoing spiritual discipline.

And I’ll just end this little walk around your question with another phrase that, as you know, is in the book. And that is: “Violence is what happens when we don’t know what else to do with our suffering.” Violence is what happens when we don’t know what else to do with our suffering. So much human suffering, whether real or imagined, ends up manifesting in violence, because people don’t know what else to do with their suffering.

Of course, what’s pretty obvious, when you think about the work of someone like Henri Nouwen or some of the work that I’ve tried to do, or many other writers and thinkers who are rooted in one or another version of the Christian tradition: Christianity is very fundamentally about other answers to what we do with our suffering. You know, Henri was very much, of course, onto that as a very Christ-centered Christian and one who helped us understand the way in which the Christ-life is about absorbing and transforming the suffering, rather than handing it along to other people.

You know, we have a person in the White House right now who obviously suffered as a child. And his wounds are now on display for the whole world to see. I’m not saying that we should feel sorry for him in a way that trumps our radical critique of his policies and practices, but he’s a classic example. And there are many others who suffer and then work it out by making the people who are under them suffer.

I noticed that often in academic life – it was one of the reasons I left academic life – that a lot of faculty who endured graduate school suffered as graduate students. And then they spent the next 40 years working it out by making their students suffer. And I just felt this is not a fit way for a grownup to live. And I know there are many exceptions to that, but I was at the time, in my late twenties, I was reacting to things that I had experienced in graduate school and simply didn’t want to swim in those waters any longer. It’s true of clergy, too. It’s true of parents sometimes. And on and on it goes, so this whole question of how we transform suffering and anger, all of those shadow-side experiences that we have, into energy that aims at being life-giving rather than death-dealing, I think is a really fundamental spiritual question. And I hope that a lot of folks in spiritual communities of many sorts will devote themselves to that question in the years ahead.

Karen Pascal: Oh, that’s good. Parker, it’s been a delight to talk with you today. I’m so grateful you could give me this time. And as I have said throughout, and I say it again to the audience listening, I want to encourage you to get this book, On the Brink of Everything: Grace, Gravity, and Getting Old, by Parker J. Palmer. You won’t be disappointed. It is a real treasure.

I wondered if by chance – and I’m kind of springing this on you out of the blue – is there any chance you’d read us one of the poems in the book? There are so many good ones. I was trying to figure out which one did I want you to read. And I thought, well, maybe there’s something in here that’s a favorite for you. And maybe you don’t even have the book near you, so can’t say whether you could read or not.

Parker Palmer: Oh, I’d be glad to. And for reasons that I won’t trouble you with, one comes quickly to mind. I think partly because my wife and I were talking about it last night, and maybe it’s even appropriate to this particular conversation that we’ve just had. It’s a poem called Harrowing. So just a quick word: I was actually on retreat at a Roman Catholic retreat center down in Kentucky in the middle of one of my three deep dives into clinical depression, which I write about in the book. And I was walking, feeling quite bereft, walking down this country road. And I passed a farm field that had been harrowed. And for the urbanites who don’t know what that is, the farmer drags a big machine over it that has many discs that cut into the ground. And it tosses up the earth. It’s after the winter freeze and sort of chops and dices, it’s kind of “Cuisinarting” the field, I guess, that tosses things up in a kind of preliminary plowing, before you do the finer plowing and then plant. And so, the look of this field became a metaphor for me. And of course, the word harrowing has a double meaning. You harrow a field, but you also get harrowed and feel harrowed. And so, this poem came out of it.

Harrowing

The plow has savaged this sweet field

Misshapen clods of earth kicked up

Rocks and twisted roots exposed to view

Last year’s growth demolished by the blade.

I have plowed my life this way

Turned over a whole history

Looking for the roots of what went wrong

Until my face is ravaged, furrowed, scarred.

Enough. The job is done.

Whatever’s been uprooted, let it be

Seedbed for the growing that’s to come.

I plowed to unearth last year’s reasons –

The farmer plows to plant a greening season.

And I’ll just say that maybe it’s obvious why that poem feels appropriate right now. We’re in the middle of a harrowing period of history. Harrowing isn’t something that happens just to individuals in depression. It happens to whole societies, to a whole planet, as it feels like we’re sort of back in the plague. And we can plow a lot – and doubtless will – to unearth last year’s reasons. There’s a role for that kind of work, because there are mistakes that we need to not make again. But ultimately, our job is the farmer’s job, and that is to plant a greening season. And the question of meaning that we can all be keeping in mind right now is, what are we planting right now that might grow from this harrowed earth in the years and decades ahead?

Karen Pascal: Thank you so much, Parker. I’m grateful for so many parts of what you’ve shared even today. We didn’t even begin to dip into the great and honest way you have been able to share about the depressions that you have lived through that have shaped your life, and then have been probably that harrowing time that became the greening that could even be a resource for others. Not just for you, but for others. I’m grateful for the way the kind of writing you’ve done has served so well the needs of others who are battling with pain and with uncertainty. And I was particularly grateful that you and I could get to talk today, because we are in a time where it does feel so much like it is total upheaval and we need voices of faith and courage.

Parker Palmer: It really does. And once again, as we end up here, a deep bow to Henri, to Henri’s memory and presence in our lives, because he was really the first person to help me understand at depth what it meant to be a wounded healer. And I remember, as I learned from him about that idea, I thought, “Yeah, that’s what I want to be when I grow up.”

Karen Pascal: Well, you grew up in that, Parker. I will witness to that.

Thank you so much for joining me today. This has been just such fun for me. I have enjoyed listening to you so much and treasure you as a friend to the Henri Nouwen Society, too. You have often jumped in at the deep end of the pool when I’m trying to figure out what do I do here, or what do I do there? And you’re so kind to give a call, or I think a word of encouragement. But again, I just say, thank you for this lovely book. And I encourage our readers: Go to our website; you’ll get the details about the book. I’ll find that picture of Henri and Parker, and share that with you as well. And we’d certainly invite you to come back again. Thank you very much for joining us today. Until next time.

Parker Palmer: Thanks, Karen. I’d be delighted to come back. Take good care. Blessings to all.

Karen Pascal: If you did enjoy this podcast, we’d be so grateful if you’d take time to give it a stellar review or a thumbs-up, or even share it with your friends and family. As well, you’ll find links in the show notes for our website and any content resources or books discussed in this interview.

Thank you again for listening. Until next time.

In the words of our podcast listeners

Sign Up for Our FREE Daily Meditations & Newsletter!

Help share Nouwen’s spiritual vision

When you give to the Henri Nouwen Society, you join us in offering inspiration, comfort, and hope to people around the world. Thank you for your generosity and partnership!