-

Joyce Rupp "Praying Our Goodbyes" | Episode Transcript

Karen Pascal: Now, let me take a moment to introduce today’s guest. Joyce Rupp is wellknown for her work as a writer, an international retreat leader, and a conference speaker. She’s the author of numerous best-selling books, including Praying our Goodbyes, Open the Door, and Fragments of Your Ancient Name. Fly While You Still Have Wings is among her publications earning an award in the spiritual books category from the Catholic Press Association. Joyce is a nun, a member of the Servants of Mary religious community. She’s a gifted poet and Joyce reminds me of Henri Nouwen in that she is a very prolific author with more than 28 books that reached deep into the hearts of her readers and fans. Joyce, you’ve been called a spiritual midwife. What does that mean?

Joyce Rupp: Well, I started thinking about that aspect of my spirituality, sharing my spirituality with others you know, and one thing I was so influenced by Karl Rahner’s theology and one of the things he said about it that has always stayed with me. He said that religious education or theology isn’t pouring something into someone, it’s drawing it forth. And that got me thinking about how I am with other people when I’m sharing spirituality or they’re sharing their journey with me. And I was so taken with that whole, not just image, but the reality of what a medical midwife is like. You know, she has to know a lot about her profession and be very in tune and in touch with the woman who’s about to give birth. She can cheer the woman on, she can have all of the information there, but she can’t do the birthing for that person.

And I really love that because I think it’s a very humbling position and it keeps me from trying to control how something’s going to evolve for another person. And also from being arrogant and thinking that I know how it ought to go. And so I’ve been so comfortable with that approach for many years now and I feel like it has served me well. And also with those that I’ve journeyed with personally, that I’ve companioned, but also with the groups I’ve been with. I love to listen to those who have come to my retreats and conferences. I have learned so much from them about how they have gone through their own spiritual growth process and how they experience life in the light of their own beliefs and values. So that’s a long response to that, Karen, but that’s basically how that all that has come about because it sounds a little strange to some people, I guess.

Karen: Well I sensed it in the books that I have read. One of the books I thought I’d like to focus on was Praying our Goodbyes: a Spiritual Companion through Life’s Losses and Sorrows. I mean, you’ve been through an awful lot yourself and you used the stuff of your wounds to bring understanding and comforting and healing to others. This book is uniquely about hellos, goodbyes and hellos. Can you explain what you had in that metaphor – hellos, goodbyes, and hellos?

Joyce: Well it really is a process of life, death and rebirth. I’ve just given it different names. But it’s that whole process of transformation, that there’s that middle, that bridge part of it, which is the part that I don’t think anyone really wants to walk across or walk through. And those are the painful experiences, the unfinished, the limitations, the harsh events that come into our lives. And yet it’s by entering into them that we move to something greater, deeper, stronger, freer in our life. You know the rebirthing or the new hello. The greeting something that’s new in our life or fresh for us, or that has been restored in a larger light, I guess. And I don’t know if I could have written that book if I had not read some of Henri’s work before I wrote that.

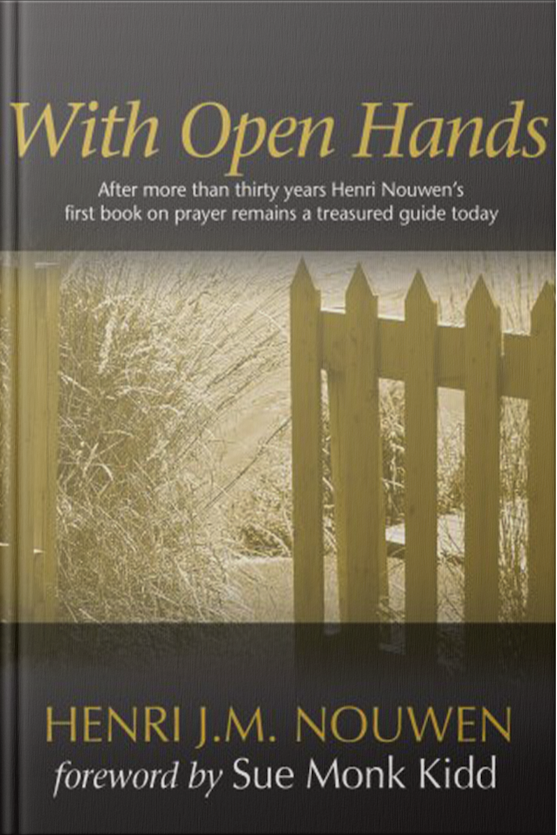

And here’s the reason why. I grew up in a farm family in Northwest Iowa and I was raised a Roman Catholic. And my family – of course when you’re a child you just think this is how everybody grows up or how everyone responds to life events — but in my family, we never talked about how we felt about anything. We were very closed about our own thoughts and emotions when it came to what was happening on the inside of ourselves. We were okay externally talking about things, but we just didn’t. And when I went to my first year in college, I remember so well that one of my professors called me in and she wanted to talk with me. And actually I was astounded. She saw in me something I didn’t see in myself. She asked me if I’d ever thought about joining a religious community and I about fell over. My response was – I’m just so uncomfortable when someone can see into me. I mean, that’s such a big statement, and, you know I gradually learned how important it is to be open and to be vulnerable. And Henri’s first book started that for me, which really was more about prayer than it was about his own vulnerableness at that time, but it was With Open Hands. And I love that book. I still go back to that book and what it did for me. That first image he has of a woman who’s holding that coin tightly in her hand and how she has to open up her hand and let that coin be there and perhaps let it go. And I have just so treasured that image of open hands, and that began to open me up emotionally, mentally, in my prayer.

In fact, just recently I was companioning with someone and I encouraged her to pray with open hands to hold what she is really struggling with and just release it, have it there, and just release it as well as she can. And so, that foundation, or that basis has been there with me through so much. And so when I came to writing Praying Our Goodbyes – I have always found loss difficult. I still do although I think I pretty much know how to go through it now, but I still find farewells and loss difficult.

And anyway, so I was writing this book because I believe people go through so many kinds of losses and until the time I wrote that book, people just kind of slid over them and thought only physical death was the goodbye that we really mourn. So I started writing that book and in the introduction, I just very briefly made a comment, a couple of lines about my brother Dave who had drowned at age 23, and I was 25 at the time. And that was just a really horrific experience for me emotionally and spiritually. So I had written the manuscript and I sent it around to a few people to read it over and see what they thought. And one of the people I sent it to was a chaplain out in northwest United States. I didn’t know him real, real well, but I respected him. So he read my manuscript and then he wrote back to me and he said, “I think that you ought to write a lot more about your brother’s death and how you felt about it, how it affected you”. And I was really upset with that because I thought, well, I can’t just bare my soul to the public. You know, I can’t just let them know that pain and hurt and how I had to work through that. But after about a week or so of settling down, I did write about it. And that was such an eye-opener for me because when that book came out, one of the things that people talked about the most when they wrote to me about it, was how much they appreciated what I had written about my brother and how they identified with it and how it had helped them to realize that they could go through their own suffering. And that really strengthened me so much in being willing to be vulnerable.

And I think of anything in Henri Nouwen’s writings, what I admire most about him, his writing and the way that he wrote, is that he was able to share his vulnerability in a way that didn’t, my phrase for it is, he didn’t bleed on the pages. You know, he named what happened, but then he took it to the next step, which was to connect it with his readers. And that’s how I became so fond of his writing, because I could find myself there and I could find encouragement there. So after that, my writing became much more open and honest and I’ve had people say to me, it’s like you wrote that just for me. Or people would say, it’s like you’re in my kitchen and listening to me.

I think that’s how I felt about Henri’s writing. I thought, how could he have the courage to write that? And yet I sure can identify when he’s talking about something that he’s struggling with or limitations that he was dealing with. So, that’s really so significant in terms of my writing, Praying Our Goodbyes.

Karen: I felt it in the book. I loved the honesty that I found there. I felt that you truly understand grief. Grief isn’t just, as you said, losing maybe- the death of somebody, but you understood the losses that are often completely unsettling our lives. Maybe it’s a job. Maybe it’s a marriage. There’s so many things that we kind of go, will I ever see beyond this moment? Will I ever get beyond this pain? And I felt I wanted to compliment you on the honesty that was there and I wanted to say to others, this book, sometimes you look for, what can I put into someone’s hands who’s going through something very hard and it doesn’t go quickly. It doesn’t go as quickly as you want. It’s one thing to say goodbye to a loved one. It’s another thing to realize the grief that you’re carrying and what do you do with that grief. But I did feel this book is just wonderful. Now you talk about existential ache in the book. What do you mean, “ the loneliness paradoxically joins us with others in their aloneness”? Tell me about existential ache.

Joyce: You know, that’s another piece, I think, of Henri’s work and I’ve experienced it for myself and it’s the kind of, uncomfortable isn’t the right word. It’s a sense of incompleteness. I would put it that way. Not necessarily for another person to be in my life, but just that there’s something missing. And I think it’s part of everyone’s life at different times. I think it’s there in the best of marriages. I think it’s there in the best of people who are dedicated to public service or people whose lives generally move along well. But I truly believe that for myself and from what others have told me that there’s just moments in our lives when we know that there’s something more and that we haven’t found it yet.

You know, Saint Augustine said, ”our hearts are restless until they rest in thee”. I think that’s certainly a big piece of it. It’s that mystery of the divine that we certainly can’t fully fathom. But I think it’s something more than that. I think it’s, especially as I’ve grown older, I think it’s a sense of wanting to really feel that oneness, kinship that I have with all of life. And that is so hard to get to, especially now I think when there’s so many differences that are emphasized whether it’s politically or religiously or any other way. But I think there are times when that rises up in us and it’s existential in the sense that it’s part of human existence. It’s just there. And not to blame ourselves for that. Gosh, if there’s something I’m not doing right, or should I be doing more or that, but I think the best thing is to befriend it and to say, ”Oh, there you are again. How did you happen to arise now? And how would you like me to be with you in this?” And for me, one of the best ways is I find so much comfort in nature. And so when I’m finding just this restlessness in me or this sense of incompleteness, if I go for a long walk and I just let my head stuff, put it away for a while and just simply tune into the walking and nature, it all kind of settles in me again. And it’s like, it’s all right, this is just a part of who you are. So I don’t know if you’ve experienced that in your life, but I found it to be there and in other people besides myself, and I’ve certainly found it in Henri’s work.

Karen: I confess I have found it in my life as well. And that’s why I wanted to have you talk about it because I think sometimes, I mean, we run fast to cover it up. We dance fast to cover it. We do all those kinds of things, but I think in some ways, there’s that moment of this incredible sense of aloneness, this incredible sense of a longing for connection that would comfort that. And in a way, at the same time, knowing that that aloneness is probably our most human connection with all other human beings, we all experience that. It is an amazing thing. Also, your book does bring forward an important question, and that is what causes suffering? Does God send it? I mean, that’s sometimes we kind of find ourselves going, “Why did you do this to me God?” So what’s your answer? What causes suffering, Joyce?

Joyce: Yes. You know, I think that for me personally, that’s one of the most important pieces of the book. And it has been the most comforting for a lot of people who have used the book. Because even people who have what I would consider a really healthy relationship with God, when something really terrible happens to them, whether it’s a sudden death of someone they love, or they go to the doctor and they find that they have cancer or something. It’s like that question comes, “Why me?” and “Where are you in this God? I thought you were for me. I thought I was a good person.” All that kind of thing. And so I really tried to develop in that particular section of the book, how suffering happens because of our human condition.

People become ill for a lot of reasons. It could be genetic, it could be something in the environment. It could be maybe they haven’t taken good care of themselves. Whatever it might be that has caused that illness. But God didn’t cause that, and I’ve looked at just a variety of things. Another big one – and I’ve had people say this to me. I remember a woman, she was in her, probably her eighties. I was speaking at a church in a rural area and this woman came up to me right before I was going to speak. And she said, “I’m in terrible pain. I have this illness. I’m sure that God is punishing me for what happened when I was 14 years old”. I mean, this woman is in her eighties. And she said, “I had a child out of wedlock. And I think that God is punishing me for this”. And, oh my goodness, my heart just broke for her. And I didn’t have a lot of time with her, but I just really tried to help her see that God certainly didn’t hold that against her. And could she forgive herself because I think that was at the heart of it. And I felt I saw some sense of relief on her face when we finished. That’s the kind of thing that I think is still there for people: “God is testing me, punishing me, causing this, trying to teach me a lesson”. And that is so ingrained in us from past religious teachings, as well as hearing it from others, reading it in some old theology and it’s very hard sometimes for people to move beyond that. But it is the most wonderful thing to see what happens when people do experience that.

Just recently I’ve been journeying with a woman, not in spiritual guidance so I can talk about this because I think it’s not confidential. But you know she’s nearing death. She’s a beautiful, beautiful woman, early fifties. And in one of our conversations, I just said, “How do you feel about your relationship with God?” And she said, “I’m really peaceful about my death. I’m just not sure, did I do enough? Was I good enough?” And I think that’s a natural thing that comes up. And so we had a conversation about that. And again, kind of based on Praying our Goodbyes, which she, without my realizing it was just beginning to read as one of her children had brought it for her. And so I just talked about, I said, “You know you are worthy in God’s eyes. Can you accept that you’re worthy in your own eyes?”

And that yes, you did make some mistakes and yes, you didn’t always choose properly perhaps, but at this moment in time your whole focus is going to be in coming home into those loving, tender, welcoming arms of the Holy One. And the next time I was with her, she said, “You know, I’m at a new place with that. And I’ve really come to peace with it”. It was wonderful. It’s wonderful to see those kinds of things that can be transforming and bring people to such deep peace. But all those old messages are there and oh my goodness, they can just haunt people for a long time, as they did with this one woman who thought God was blaming her, punishing her for having that child.

Karen: You know, it’s funny. I want to say that this book is for everyone. I’m just going to say that. In reading it for the first time, Praying our Goodbyes: A Spiritual Companion to Life’s Losses and Sorrows – it isn’t just about end of life issues, but there are losses all the way along and often we play out in our mind that sense God is punishing us, or we failed. And I found this just rich with understanding and godly wisdom. I just found it something that would be a great refresher when you go down the wrong road and you have to come back and find the way. I think this is a good book for finding the way. And I compliment you on that.

You talk about creative suffering. What do you mean by “creative suffering”? None of us kind of welcomes that, but I think there’s some great truth to that. And often we can look backwards over our lives and some bend in the road turned into something. Tell us about creative suffering.

Joyce: You know, I’ve been mocked for that phrase. And probably if I had to rewrite the book, I might not have used that. But what I really meant by it was that, depending on how we move through our suffering, it can be creative in the sense that it can lead us to something new. Just an example from my life and again, I go back to Henri and, and his writing. One of the first books I ever read on compassion was that beautiful book of his, he coauthored with McNeill and Morrison, and it’s just called Compassion. I think I read that shortly after it came out. I think it came out in the mid-eighties and I was so taken with it. First of all, because in my religious community, our devotion is to Mary standing at the foot of the cross. And so our central devotion is to be with people who are suffering in a compassionate way. And I thought, oh my goodness, this book has just this most beautiful quote – in fact I have it with me because I wanted to mention it to you and to those who are listening. And it has helped me so much. And this does tie into creative suffering. It just is the most beautiful image of how God is with us in our suffering. And this is what they wrote, and Henri wrote, “Compassion, asks us to go where it hurts, to enter places of pain, to share in brokenness, fear, confusion, and anguish. Compassion, challenges us to cry out with those in misery, to mourn with those who are lonely, to weep with those in tears. Compassion requires us to be weak with the weak, vulnerable with the vulnerable and powerless with the powerless. Compassion means full immersion in the condition of being human.”

You see how I go through my suffering– if I resist it, if I deny it, if I shove it aside, if I get angry and resentful about it — and I never go deeper to let it accompany me and teach me, I can’t do these beautiful kinds of things that are here. To share in other people’s brokenness and fear and confusion and anguish and to be with those who are lonely without trying to fix them. I think it’s that same section where the ending part of it is — and I’ve always loved this — that God goes to the most forgotten corners of the world and will not stop until all the tears of the world have ceased.

And I just think that is so gorgeous. Think of this comforting, compassionate, divine being going to all the corners of the world, who goes with all people who are suffering. So going back to creative suffering, here’s one of the central ways that what I have experienced in my life has really helped me to be a person with empathy and compassion. It was about 2009 I had this graced moment in prayer when I just felt called to learn and teach compassion. And I started a program with Margaret Stratman in my community called Boundless Compassion. And it has grown and blossomed and matured. I wrote a book about our program, finally a couple of years ago. We started training other people to teach the basic foundational concepts of that book. Right now we have about a hundred trained facilitators, and 10 of them are in Canada. And we have 25 more that we’ll train at the end of June. And then in October, we’ll have about 30 more. And it is wonderful to see how they’re carrying on this in their own professions and with their own gifts and talents. And honestly, I never could have done that without understanding what it’s like to not just to experience as you said, physical death, but rejection, the loss of friendship, failure in a job that I had. There’s just been different kinds of ways that once I got done fighting what was happening, and I really entered into that suffering in the sense of, I need to be present to this, I need to listen to how my body, mind and spirit are responding and be self-compassionate, and I need to take it into prayer every day– it’s just growing me tremendously. And I know I still have a long ways to go.

Christina Feldman- I love this line in our book on compassion- she said, “We’re always beginners in the art of compassion”. And I feel that’s so true. I think Henri would agree with that. He was always learning more about how to be compassionate in everything that he experienced. And he certainly did keep growing in that. So that’s really what I mean by that creative part, that it creates something; something that we didn’t anticipate in ourselves or in the way that we live or the way we relate to other people.

Karen: I must admit, I saw some of the conferences and events you have planned. And I want to encourage everyone go to Joyce Rupp’s website and sign up. I love what you’re saying. I mean, I really think that’s a very valuable place to enter in, a door to go through into that world of compassion. And you’re right, it was very important to Henri. It was central to him. It was that ongoing lesson that he was working on. One of the things you say in your book, you say there’s a time to move on to let new melodies break forth in our hearts.

I want to just do a little change here and say, was writing the memoir about your mother, which is, Fly While You still have Wings, a way of letting go for you?

Joyce: It was a big one. You are very perceptive, Karen. My mother and I had a wonderful friendship. She lived 14 years after my dad. My dad died at 70 instantly of a heart attack. And my mother went on. My mother was a very resilient woman and I admired her greatly. And after my father died I would invite my mother to go with me when I was traveling around the country to different places to speak or give retreats. And she loved that because she didn’t get to do a lot of that before my father died. And we had wonderful talks. And then as she was in her late seventies, she had a lot of physical health issues and I saw how she was really failing in health. And I so admired her because she talked freely about her death. In fact, she was so amazing. One time I came –she lived about, it was six to seven hour round trip for me to go and visit my mother. But whenever I would visit her, we’d have these great kitchen table conversations. And one day when I was there to visit, she said to me, “You know, I went down to Greenwood’s funeral home last week and I just made all the arrangements for my funeral. I ordered my casket, I did the prayer card.” And she went through all this and I was like, just aghast, you know. I was like, how can you be talking about that. I don’t want you to die. Let’s not talk about it. But at the same time, I knew from my experience of working with grief and loss that I needed to let her talk about it. So I did.

But from then on – I think that was maybe when she was just 80 or 81, she died at 84, – I started being really attentive to things that she said and how she was with her aging. And I would write them down in my journal. So I had a lot of memories later on. So then my mother died and she died actually rather quickly. She went into the hospital and three hours later, she died. And I thought initially that I was okay. I knew that she was comfortable with her death, but wow. I mean about a month or so after I just, I mean, every day I really missed her, but all of a sudden I was filled with these regrets. Oh my gosh, they just bombarded me. And they were crazy little things. It was nothing major because we never, ever had a fight. We never had a separation. But they were things that I so wished I would have done that I didn’t do. That I didn’t understand about what it was like to age. And they were just like – one of the things that I never realized until I went back in my journal and I started reading what I had written. When it was her 83rd birthday, I had made a point, I was going to go home and I was going to help her out because she was pretty much confined to being in a chair. She had a walker, but she couldn’t do a whole lot. And my mother had always been an immaculate housekeeper, but the last couple of years, she just couldn’t do that. She had someone come in to help. But anyway, so I said to her, “mom for your birthday, I’m going to clean your kitchen cupboards”. And so she’s sitting in the living room and I’m out there and I’m just working away thinking, “I’m so great about doing this for her.” And all of a sudden she called me into the living room and ,I can’t remember our exact conversation right now, I know I’ve written some of it in the book, but basically what she said to me was she didn’t care at all about my cleaning the cupboards, what she wanted me to do was sit and talk with her and be with her. She didn’t say that directly because my mother had a hard time with that. But when looking back on that, I mean I had this conversation, I sat next to her for a while, then went back to cleaning cupboards again, instead of spending that precious time with her.

And, I so regretted what I had done. I didn’t ask her how she felt. Did she want me to just to be there and be present with her instead of cleaning those stupid cupboards, you know? And there were other situations like that. I just missed with her. I just simply missed it with her. One other time that I really regretted, this was just a few months before she died, and I was in her bedroom. I was helping her to make her bed. And I noticed her mattress wasn’t the best. I said to her, “You know, mom, we need to get you a new mattress.” And she said to me, “Oh no, that mattress is just fine”. I said, ”no, no”, I said, “we need to get you a new one”.

And she says, “You know, I don’t think I’m going to be around for very long.” And you know what? I wouldn’t let her talk about it. I said, “Oh no, you’re going to be around for a long time yet”. And I just dismissed the whole thing. And I thought afterwards, I so regretted it. It would have been such a precious moment to say, ”What’s it like for you to feel that you’re so close to death? How do you know that in your body and your mind and your spirit?” But I never asked her. So I had all these regrets and I wanted so much to write a book about my mother’s aging, because I thought it would help other people to not make the same mistakes that I had made. But I couldn’t write that book.

My mother died in 2000 and it took me 10 years before I could finally go back to my journals and start culling them and find out what I had written about my time in her later years. And even then I was dragging my feet about that whole thing. And finally, I went for a week to a… it’s called Mallard Island, a beautiful island on Rainy Lake that writers go to for special time away. And I was still beating myself up about the regrets, but dragging myself to try and write this book. And one morning when I was there, I went to a place called the Japanese house, and it sits on the end of the peninsula of the island. And it’s a beautiful, oh, just a gorgeous spot, this tiny house. And it looks out onto the water and two other islands nearby.

I just sat there and I just prayed I could let go of those regrets. And the most amazing thing happened to me. I’d go early, like about five in the morning and be there for a couple of hours usually. And towards the end of my time there, I looked out on the water and all of a sudden I remembered how I had read this story of the River Styx and how the Egyptians had placed their deceased ones in their boats and put lanterns in the boats and sent them out on the water and let them go. And in that moment, the most grace came to me and I thought it is time to let my mother go. And it is time for me to let my regrets go. And honestly, I have never had those regrets since then. I came back, I wrote the book. I felt good about what I wrote. And that all changed for me. Again, I go back to Henri’s writings and I think, you know, he wrote that beautiful book In Memoriam about his mother and his grief over his mother’s death. And that really gave me the strength again, I think, to walk into my own grief with my mother’s death. Because writing the book was hard because I had remembered all the good things about her and what I missed about her. And then it was that chapter I wrote – the chapter, I just named A Book of Regrets. I asked a friend one time. I said, “Did you ever have regrets after your mother died”? And she said to me, “I was a book of regrets”. And I thought, oh I’m not alone.

Karen: It certainly comes alive to me. I think about my own mother’s passing. And I think about how I was afraid to even go there. I danced so fast after she died, just because a part of me was afraid of all the anguish that was there. My father had died when I was six years old. So I knew what it was like. I had kind of a childhood fear of losing my mother. And in that childhood fear of losing my mother I was afraid to go there and even feel the sorrow that I would feel. I just danced fast until I finally settled back and could cherish that I had had such a wonderful mother and that I could enter in. But I find what you wrote was so good because I think that book of regrets, all of us think we could have done more.

What could we have said, what should we have said – the should haves and would haves of our lives? And I found that very valuable that you wrote so honestly about that. It’s interesting because I find that as I’m reading this, I kind of came away going, “Are you teaching yourself how to age?” Because you were very raw and honest with the process that your mother went through. She was a person who had been so independent and the loss of mobility and the loss of productivity obviously was a tremendous loss to her. She wasn’t comfortable having other people do for her. But in that process I find the book quite useful because it doesn’t matter what age you are. There are going to be points in our life where we have losses and in those losses, are we able to receive from others is a big issue, I think. And are we able to be comfortable in those stages? But I found myself feeling that you were maybe writing the book for yourself because, you too. We all come to the end of our lives. We all come there. How will we cope with not being able to do things, being dependent?

Joyce: So you just named that so well, Karen, and you’re so right. You know I’m going to be 78 pretty soon. I’m almost at the place where my mother died. I’m in very good health, much better health than my mother ever was at this age. But you’re right. I did write that book for myself and, you know, a piece of it that I really wrote for myself was naming how independent I am. And I got that from my mother and it’s hard to lean on other people. Again, I think Henri learned how to do that. I mean he overcame that for himself. And I think that is so important at any stage in our life to learn how to be interdependent; to lean on others when we need to, not overly, but to go there when we need to. I think it was after the book came out –my mother’s motto was “fly while you still have wings”. I mean that’s how she was. But anyway, I decided I needed to start really receiving from others. So, my hair by then was starting to turn white and I was still traveling a lot to give talks and conferences and I’d get on the plane with my little light carry on and I could easily put it up. I’m pretty strong, and so I could put it up above. But some guy would come along and say, oh, here, let me help you with this. And I so want to say, hey, look, I might look old, but I can put that up there by myself.

But instead I learned how to say, “Oh, thank you so much. That’s really a big help,” and then sit down and swallow my pride. And just little things like that. One time I was with my young cousin I dearly love, and we were crossing the street and Katie took my elbow to cross the street and I wanted to just shrug it off and say, “I’m not an old lady. I can cross the street by myself.” But I didn’t. I thought, she sees me as an old person and it’s just an act of love and so receive it instead of fighting it. Right now I meet with a group in my community. All four of them are in their nineties and they’re mentally still very alert but physically not in such great shape. Anyway, I learned so much from them as they tell me how they have moved into letting go of this strong desire to take care of oneself completely and value and appreciate and be grateful for the assistance that they receive in a variety of ways.

There’s so much to learn. I’m hoping someday to really write a book just about elderhood. I keep learning so much from it.

Karen: You’ve obviously been accompanying a lot of people in this process because you’ve been involved in the Boundless Compassion program. You’ve known what it is to accompany people. And that’s quite important. I loved your poetry in this book. Is there a chance I could get you to read a few of the poems? What became central obviously, almost in the middle of the book, is Fly While You Still Have Wings and the poem is Fly. I see this image of flight and then it evolves. I don’t know if you have a book in front of you, if you don’t…

Joyce: I do have it with me, Karen. I didn’t know you were going to ask me to read something, but I’d love to read something.

Karen: I have a few that I’ve marked that I just go, oh, I just love these poems, but let’s start with that one simply because that was kind of the heart of your mom’s message for herself. It was like, keep going while you can.

Joyce: You know, I love to write poetry. Not everyone gets poetry, but anyway, I love to read this whole. Here we go. Okay. This is from the chapter Fly While You Still Have Wings and the introduction to that chapter.

Fly. Fly, while you still have wings

Fly with buoyancy

Do not falter in fervor or waiver in eagerness.

Lift off with a zestful spirit

Enter fully what remains of the fleeting, diminishing years of life

Do not wait to follow what the heart truly desires.

Fly now.

Take yourself out the door into fresh freedom.

Celebrate what awaits

Spend yourself like there’s no tomorrow

Because there may be no tomorrow.

Open your heart to receive latent possibilities of joy and loving, lasting memories.

Fly, fly, fly while you still have wings.

Karen: You’re a beautiful poet. Spend yourself like there’s no tomorrow. It’s beautiful. It’s beautiful. I think you inherited some of that incredible resilience of your mom. And it was quite beautiful. I have another favorite. It’s on page 153, Soul Contractions. Would you read that one as well?

Joyce: The sun porch one. That was such a wonderful experience for my mother on that sun porch. So the title of this poem is Soul Contractions.

My mother ages all too quickly now.

The latest illness claiming more chunks of her vitality each day.

This beloved woman whose womb held my body,

I now hold in the chalice of my vigilance.

Sadness and sorrow pulse inside my spirit.

A kindred, soul contraction resonating with her spiritual gestation,

as she prepares during these final years for her birth into eternity.

Dear mother, I who burst forth from your womb on a sunny morning in June,

embrace you now with gratitude, praying to let you go freely

to encourage your spirit to wing forward peacefully

into the mystery of the One Great Womb,

where there is space enough to embrace us all.

Karen: Wow. That is truly lovely. Joyce, I just thank you so much for who you are and what you bring to us. And clearly, God’s gifted you with wonderful insights and the ability to really communicate and encourage at a very deep level. That’s what I found in your books. That’s what reminds me most of Henri, this deep honesty, this fresh honesty that you bring and that sense of intimacy, understanding the human heart and understanding the heart of God. I just see those two meeting beautifully in your writing and in your teaching.

Joyce: You speak like a poet. Karen, are you a poet?

Karen: I’m not, but my heart lights up with poetry. So it was a thrill to discover you were a poet. I mean, it was really woven through your writings, obviously. And I’m getting to know you through your poetry as well. I appreciate that very much.

Joyce: I have one book of poetry and I actually had two; one’s out of print. My soul feels lean and it’s really in two parts. And the first part is about the difficulty, the darkness, the depressions and everything people face. And the second part of it is all the poems are about hope and newness and freshness and springtime and that. Anyway, I was so grateful to be able to publish that book of poetry because not all publishers want to publish poetry, unless you’re really a well-known poet. I love poetry because you can say so much in really small space if you keep working at it and you can say it in a way that it really catches the heart and it connects. I loved your phrase ‘the intimacy of the heart’. I think that that’s what poetry is, at least for me, what I really appreciate about it. So thank you for mentioning that.

Karen: Well you are welcome. You have fed my spirit. I’m grateful and I encourage others – do get Joyce Rupp’s books. You’re going to be in for a treat. I think I would especially say, this, Praying our Goodbyes is vital. It blessed me so much. I have another one here that is just wonderful is Essential Writings, which I really enjoyed. The Modern Spiritual Masters series. That gives a good tasting of many things. And of course, the book that you have written in a way as a tribute to your mom and as a guidebook through the goodbyes and hellos and hellos and goodbyes of life. I just think it’s a beautiful book: Fly While You Still Have Wings. Thank you so much Joyce for being with us. And I will encourage all of those listeners to be sure and follow up and find these good treasures. I’m sure they’ll enjoy them.

Joyce: Well Karen, thank you so much. I’m just so delighted that we had this conversation. Because it just takes me back into, how did I get to be where I am today? And that’s always a good thing. I think life leads to gratitude and kind of wonderment. So thanks a lot. And I so appreciate your affirmation and your interest and I wish you well on your journey.

Karen: And I appreciate how much Henri Nouwen has impacted you. You’ve told that part of the story so well, and I’m always looking for those people where I can say, are we kindred spirits on that level too? So that was a delight to sort of hear the way in which Henri has woven his understanding of life into yours. Thanks so much, Joyce. Blessings

Joyce: You’re welcome. Take good care. Bye now.

Praise from our podcast listeners

Sign Up for Our FREE Daily Meditations & Newsletter!

Help share Nouwen’s spiritual vision

When you give to the Henri Nouwen Society, you join us in offering inspiration, comfort, and hope to people around the world. Thank you for your generosity and partnership!