-

Gabrielle Earnshaw "The Prodigal & the Pandemic" | Episode Transcript

Karen Pascal: Hello, I’m Karen Pascal. I’m the Executive Director of the Henri Nouwen Society. Welcome to a new episode of Henri Nouwen: Now and Then. Our goal at the Nouwen Society is to extend the rich, spiritual legacy of Henri to audiences around the world. Each week we endeavor to bring you a new interview with someone who’s been deeply influenced by the writings of Henri, or perhaps even a recording of Henri himself. We invite you to share the daily meditations and these podcasts with your friends and family. Through them we can continue to reach our spiritually thirsty world with Henri’s writings, his encouragement and of course, his reminder that each of us is a beloved child of God.

Now, let me take a moment to introduce today’s guest. Gabrielle Earnshaw was Henri Nouwen’s archivist for 16 years at the University of St. Michael’s College. Today she’s the Henri Nouwen Legacy Trust archivist and consultant. Gabrielle co-edited the book Turning the Wheel: Henri Nouwen and Our Search for God. She also is the editor of many very important books drawn from Henri Nouwen’s writings. Gabrielle assembled Love Henri, the first book of Nouwen’s letters. Then she edited You are the Beloved: Daily Meditations for Spiritual Living. And most recently she was the editor of the book Following Jesus: Finding our Way Home in an Age of Anxiety.

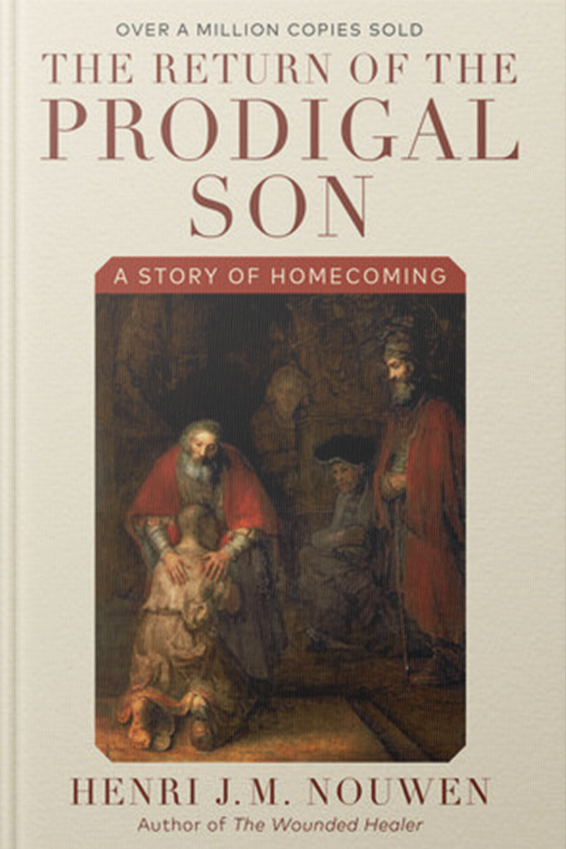

Recently, I read a beautiful article Gabrielle had written addressing the question of what has Henri Nouwen to offer to us in the midst of this pandemic. She delved into Nouwen’s classic The Return of the Prodigal Son to see if there were things Henri discovered and shared in this book that would serve us well in this crisis we’re embroiled in. Gabrielle what did you discover? What did you find that was helpful for us today in Henri’s Return of the Prodigal Son?

Gabrielle Earnshaw: Well, you know, it was an interesting exercise to go back to a book that I have read very carefully over the years, a book that I feel like I know very well. But to read it again through the lens of the pandemic, it brought certain themes more to the forefront and I was able to draw connections between what I’m living right now, what we’re living right now, and what Henri was living all those years ago. You might remember that his book actually starts in 1983 so it’s a long time ago from here in 2020. But in 1983 he sees a poster of Rembrandt’s painting of The Return of the Prodigal Son, Jesus’ parable the return of the prodigal son. And then he enters into a nine-year, what he calls, spiritual adventure with this painting. And the book outlines some of the ways that the painting was able to transform the way he lived his life, the way he lived his life from a very sort of nervous, restless, self-rejecting person into somebody who dared to say, I would like to become not just a returning child to God, which is what the parable is about, but also to actually be like the father in the parable and in the painting, which meant being a very loving person. And I think that’s the primary thing it underscored for me is that this pandemic is asking us to really look inwards and say what is a priority for me right now? What is it that I’m being called to right now? And I think a lot of us are hearing that we’re being called to love and love meaning being kind, being patient, being generous, being forgiving. Our society, our world is in a lot of pain right now. And the more of us that can claim that love and be love, I think the more we can transform this pandemic into something that possibly might be healing for the world.

Karen: What do you find that as we look out and we see, in a sense the fear that’s there and we see the reality of being forced into isolation. What do you find people in a sense naturally doing, in a sense busying themselves with, or whatever, because yes, this might be the deeper journey? But what do we tend to do that may be something we have to identify and then make some other choices?

Gabrielle: Exactly, exactly. I think that, myself included, some of the ideas are to distract ourselves from the pain that we’re actually part of here in this world. I mean, the world was aching before the pandemic started. We were already in a climate emergency and today is Earth Day. And I think that we’ve already been in a way in a mourning period, in a grieving period for the world– that is the earth– that is in so much jeopardy. And now we add in the pandemic, which is adding a lot of suffering on a very, very real visceral level for a lot of people. And I think it’s human nature to try to distract ourselves, to try to find things that are funny or to connect with people. And all of that is very good. I think Henri might caution us with distracting ourselves too much. And in fact, he talks about homecoming and we can use homecoming as a nice metaphor, but I mean homecoming can mean coming home to ourselves. And maybe at times during our days, instead of choosing to distract ourselves we might choose to just spend some time in stillness. Stillness might also include silence. And when we’re choosing stillness and silence we might then sort of turn our attention from our thoughts and from our worries and our anxiety and turn towards what Henri calls Presence. And for Henri, Presence was in us and all around us. And we can be attuned to Presence at all times, but it does help to be still and to be quiet and to carve out some time in our days for Presence, for listening to God. There’s lots of words for God and one of them is Love, so listening to Love. One thing that Henri’s book The Return of the Prodigal Son whenever I read it I always had to remind myself that yes, the parable is about us returning to home, returning to our home base, our home plate of love, but it’s also about receiving love. Henri,as a lot of people who know him and read him understood, was a person who had a propensity for self-rejection. He often felt like he wasn’t good enough or that he had to kind of make himself, I don’t know, more successful or more followers than he had. He had at his core this self-understanding that often felt like it was not worthy.

And the nine-year spiritual adventure that he outlines in the Prodigal Son is really about him claiming his goodness, claiming his worthiness and that involved him, like the younger son in the parable, of receiving God’s love. And in the painting and in the parable the son is kneeling at his father’s feet- with his head on his father’s chest. And there’s a kind of way that we too need to stop running around and looking for things and actually just come back and receive God’s love. Henri’s got this wonderful way of saying, for most of my life I’ve been out there looking for God when all the time God was looking for me and that’s about homecoming, right? That’s about coming back to ourselves. And I think that this pandemic as anxiety producing as it is with real concrete worries for people we can also make that a discipline, make that a practice of spending time with God and receiving God’s love.

Karen: I love your phrase there about carving out time or empty space for God. But it’s interesting in that image, if we just focus on that first image of the, if people see the picture,- by the way, we will have that on our website, that you can go and see that picture if you’re not familiar with the picture that inspired Henri, it’s important for you to see this image. There is this beautiful, beautiful Rembrandt image and the son is just kneeling in, I think the word that occurs to me is exhaustion. And I think there’s a certain level of exhaustion right now that we’re all facing with the pandemic. There’s a kind of flurry within us because we don’t even know where we’re headed and we’re weary of everything that it’s demanding of us. And yet it’s demanding more and you’ve got this figure collapsed in a way, and just receiving the fact that the father loves that child, that child that ran away, that child that left and rejected and said, ‘I don’t want any part of you.’ Apparently, when you ask for your inheritance before the father dies, you’re really basically saying, “I wish you were dead, dad.” So, I mean, there he is, this kid is coming back and just wants to be a servant in that household because he knows his father treats the servants better than he’s been treated. But there we are. That is a profound image.

Is there more that you want to explore in that, or can you also help us understand some of the other images that you think speak to what we’re going through right now?

Gabrielle: Well, I guess there’s one thing about the younger son, if we want to stay with him a little bit longer. I mean, he had essentially followed his passion, right? He had, yeah, he had said to his father, “I want my money now, give it to me now,” which is akin to saying that he didn’t mind if his father died. He wanted the money now. He went out and he followed his passion and for a while he had a really good time. But then eventually the money runs out and he has to think about how is he going to live from now on? And that could be a parallel to what we’re living as well, in terms of as a society, have we been squandering the resources that we’ve been given? And I am referring specifically to the Earth’s plenitude. And have we been as a society, as humanity, have we been taking it for granted and exploiting it too long and is this moment, this pandemic moment, the time that we’re sort of stopped in our tracks, and can we look beyond the fear, move beyond the fear and ask is this a moment that I can come to my senses? Like the younger son, he has come to his senses. And when he does, he starts that journey back home. And I think that that’s where we might think about how could I begin my journey back, home, my journey, back home to goodness, and to being conscious of how all of our actions impact the interconnected web of life.

Karen: That’s good. That’s really good. I love that image, that it’s important for us to realize that the father longs for the child to come home. There is no, “where have you been, what have you been up to, give me an account of what you did.” There’s none of that. “I’m so glad you’re back.” And I think that was what I found so rich in Henri when I had the opportunity to interview him about this. It was just that, “I’m so glad you’re back. I’m so glad you’re back,” and that God doesn’t meet us with judgment and “What have you been up to?” but he meets us with a welcome that says, “You are my beloved, you’re my child and I want you back.”

Tell me about the older brother. Did you get anything from that that serves us at all?

Gabrielle: Oh, the older brother,- for a book I wrote about the Return of the Prodigal Son I read through a lot of letters that Henri Nouwen received from readers. And I didn’t do an exact poll, but most of the people who are writing to him were saying, “I really relate to the older son.” Some people related to the younger son, but most people related to the older son, because he’s the one who’s dutiful. He’s the one who followed the rules, did everything right and stuck by his father when the younger son abandoned him, rejected him. And yet as Henri Nouwen and Rembrandt – I love the way that you suggested that people look at the factual painting, because the way that it’s painted the older son is outside the main pool of light. The younger son is kneeling with his head on the chest of his father and the older son is looking on with his hands clasped in front of him kind of like a shield and he is no closer to being home than the younger son. He is actually imprisoned by his own resentment and his bitterness at his younger brother. And I just wonder if, like I know within myself, I consider myself quite a dutiful person, I’ve done all the right things, I feel like anyway. But at some point the way that Henri writes about this painting in the parable it asks me to ask where have I become judgmental and bitter around other people. And where is that holding me in a kind of a vice grip? And because the way that Rembrandt has painted him, he’s very stiff. He really can’t celebrate that his brother is back, this is not good news for him. And that means that his heart has become constricted. And I think as people who are trying to live you know, in Jesus, following Jesus’ example, our hearts are meant to be open. And if there’s any part of ourselves that can identify where we’re constricted and then work towards opening it, I think that that’s going to add to the love in the world. And I think that that’s what Jesus’ parable is asking us to consider; where are our hearts constricted and making it impossible to love people, to forgive people, to step over our wounds. How do we live our wounds? Sue Mosteller once said to me that–or I heard her say that– Jesus was wounded in life and he left life whole, he left life loving. And I think that that’s what we’re called to as well. So the older son or he could be the older daughter is really calling us to step over our wounds so that we can join this sort of rush of love for humanity, for animals, for nature. It’s returning back to our loving nature I think.

Karen: It’s interesting because I think one of the things that inhibits us in that is being right, you know, so convinced we’re right. And it’s interesting because what that image really releases is the power of forgiveness. Forgiveness starts everything back at the beginning and all of us long for all sorts of parts of our life to have been erased so we could start with a clean slate, a really clean slate. And the father offers a clean slate to the son that ran away. But I think there’s clean slate for the one who got so caught up in being right and became so rigid that there was no room for anything else. It’s quite powerful.

Tell me about the father in the image, because I think it’s interesting that ultimately Henri gets called to be the father and that is profound for all of us because we can’t even envision that our gift is to welcome others home.

Gabrielle: Yeah. I think that that’s the great challenge of the book as well. I mean, and I think that all of us right now are called into that in a very direct way because I think a lot of us are being called to step into spiritual adulthood. So to stop being the children as important as that is. I mean Henri does say this in the book that it’s very important that we claim our sonship and our daughtership meaning we claim our identity as sons and daughters of God and that we claim our belovedness that’s very important. But then there is this next challenge that did take Henri Nouwen a very long time to get to. So I don’t want to put too much pressure on any of us, but it is to become the mother/father, to become in a way, — What is a mother? What is a father? What is God? God is a generative, creative, loving, forgiving presence. And that’s what we’re called to. And Henri specifically spoke about blessing, being a source of blessing. And by that he meant that we lift other people up and he goes so far to say, and to not expect anything in return. So that’s why in the last quarter of the book when he is speaking about being the father, a lot of that chapter is about how difficult this is because there’s a kind of reciprocity that we expect from, you know, I give you something and you give me something back. And really there’s a transactional quality to human love and Henri is being called and he accepts the call. And then he asks us to accept the call of being more in a kind of God’s way of loving, which is to bless people without expecting anything in return.

And I think the pandemic that it’s very important. I think you know, that Henri Nouwen suggests three ways of being able to claim this call to being mother/father and to be that source of compassion. And he has three ways: one way is to have a discipline of grieving, which I think is really applicable to today. I think that we acknowledge and we spend time in lamentation, our prayers can contain lamentation, the psalms. I find myself turning to the psalms because there’s this, ‘Why, God? Why, God?’ And I think that we can give time over to grieving.

And then the second of the three is that we be forgiving and you’ve mentioned that, is that we have a practice of forgiveness. Forgiveness is very, very difficult. And of course Henri wouldn’t be saying, except any kind of physical or psychological harm. He’s not talking about that. But he is saying that there are places in our lives that we can forgive. I mean, when in the story in his book which was a very pivotal moment is when he forgave his father for not being the father he wanted. And he had spent pretty much his entire adult life wishing that his father loved him in the way that he needed to be loved. And after a very severe accident in which he was in a precarious sort of life or death state, he came out of the accident with this real desire to forgive his father. And when he did, that’s when he was able to really consider being the father in the parable, to being the compassionate mother/father.

And then the third aspect that Henri says helps us is to be become compassionate people; people who can really feel the suffering of the world and enter into it, is to be generous. And it means generous with our time, with our gifts and of course, with our resources and generosity, kindness, warmth, this is what will generate transformation in our world. And I think that maybe those would help all of us who see the value and the importance of stepping into our spiritual maturity, into our adulthood to do that.

Karen: I wonder if another ingredient in that is actually gratitude, and it’s hard right now to be grateful. It’s like it’s a fresh beginning in our lives. It was easy to be grateful for all we have. There are people right now facing losses beyond what I can even imagine and my heart just goes out to them. We’re all trying to find our footing on ground that seems to be shifting underneath us. But I do think there’s an incredible power in a gratitude for the smallest of things. And then being great resources of love to other people and resources that are, if we can be resources in physical ways wonderful. If we’re limited because we’re not allowed outside our doors certainly we can be so supportive of all those who are making life go on for us right now in such an amazing way, whether they’re the people that are across from us when we go and buy groceries, or they’re the person that’s caring for someone we love in a hospital setting right now. There aren’t really words that make this time make a lot of sense, but we are all in there together that we know.

I was curious about something that I wanted to ask you about. And that was what part did reading the Bible have in Henri’s life and how did he read it? And are there any lessons in that for us that we might find useful right now? I’m thinking about – there’s a word Lectio Divina, but I don’t know if everybody knows what that means, but how did Henri read the Bible? Like, I think he did it daily, but what did he do with a passage? How did he approach it?

Gabrielle: Well, yes you’re right. I think that he used Lectio Divina, which is taking scripture or passages from the Bible and reading them very slowly, repetitively. And then allowing the words, the meaning of the words to descend from the head to the heart. So it’s a kind of meditation, it’s a kind of sort of rolling those words around in your heart and seeing which ones have resonance. I think Henri did that with scripture. So he entered into the scripture as though he was walking around in the passage with the people who were there. And a book that I recently edited of Henri’s – a talk that he gave called Following Jesus, and in that he does a lot of this where he gives us really good examples of how to enter into a scriptural passage. So he’ll say, get in there, be each person in the passage. So the book The Return of the Prodigal Son is actually Lectio Divina and Visio Divina, because Visio Divina is when you take an image and you do the same type of thing. You don’t look at it and analyze it so much as gaze at it and internalize it and kind of ask questions, like, ‘How does this relate to my own experience?’ And in fact, The Return of the Prodigal Son is a master class in how to do this with both the written parable, but then also how Rembrandt painted it and how then Henri is able to see it.

So it really is with the parable, he becomes each of the people. We didn’t talk about the, you know, he talks about the observers. Rembrandt painted a few people sort of lurking in the background, and they’re watching this reunion, this return home and Henri places himself as each of these observers. And what are they seeing and what’s happening inside their own hearts and souls? So I think Henri had both, he used his imagination a lot. I think he would encourage us all to use our imagination to try to enter as much as we can our whole person into a scriptural passage. I liked what he said once that often that the word that really resonated with him in his morning prayer, he would take it and kind of place it in an inner chamber of his heart. I kind of think of it like an inner library or an inner reading room and the word would be there. And he said that then throughout his day, that word would somehow have meaning for other people. He would meet people and that word would be so on his heart that somehow he found that the people coming to see him or asking him for spiritual direction would be fed by that word as well. So there’s a kind of way that the word can kind of incubate in us. I think that’s some of how he read. He also was a scholar and did a lot of reading himself, but in terms of his morning prayer and his evening prayer, I think that’s how he used scripture for his own spiritual development.

Karen: There was another idea that I think you might help me understand, and that’s the idea of spending useless time, or a uselessness of our time. How did Henri… tell me a little bit about that? I don’t quite understand it.

Gabrielle: Yeah. I love that about how he would say this to a classroom full of Harvard Divinity school students, and people, I would say, and I put myself in this same group – I mean, we’ve been told that we need to be successful. We need to be productive. We need to have a to-do list in the morning. And then at the end of it we can see that we’ve checked off all of our things on our to-do list. We’re very task oriented, step oriented, you know, five steps to losing weight and all of that. So when Henri says that we should be useless in front of God and with God, I mean he is so countercultural and he knows exactly what he’s saying.

He himself was a person who strove to be relevant. He strove to have his book on the New York Times bestseller list. I mean he absolutely was a driven person, but what he came to understand was that God and Jesus are calling us to something very different, very different. And one step in that is to get off of the productivity train and just step off of it and be completely still, I think it does have to do with stillness. I think it has to do with solitude. So there’s this idea that we spend time alone with God. Henri also talks about hiddenness, the hidden life of Jesus and the hidden life that we can also adopt. This is not something that we do to look good in other people’s eyes. This is where we’re literally just resting. You mentioned resting at the beginning and I think that it’s very, very important for us to think about that rest as a priority and that we rest in the hands of God. Richard Rohr once said that for him, prayer and meditation is climbing into the lap of God. And I just love that image because again, you know, babies especially, and even little children, when they’re sitting in their caregiver’s lap they’re resting and they’re just being, and it’s a beautiful state to witness. And we love being around toddlers and babies because of that. Animals tend to do it as well. And I think Henri is encouraging us to just rest, be useless. And he is using that word useless with a lot of consciousness, knowing that our society is telling us at all times to be useful and that if we haven’t contributed to society that day what were we doing?

I think it relates to his the concept of fruitfulness which when he talks about aging and consciously aging, he’s talking about thinking about our lives as being fruitful in that after we’ve died, after we’re completely useless, after we’re completely hidden, will our lives bear fruit. How will the love we shared, how will the forgiveness we offered, how will the blessings we gave, bear fruit for future humanity. I think that that’s all tied into that idea of being useless.

Karen: Well, it’s funny, some of us are experiencing a sense of uselessness imposed upon us. We can’t go to work, or we can’t go out our door. We can’t visit with the people we want to visit with in person. I’ve been experiencing something personally that has been very powerful for me. The start of my career was as an artist and I had a studio and for the first 10 years of my becoming, the story of my becoming, that studio was the place where I created, but it was also in the midst of that, the place where I really met God in a very, very intimate way. It was profound for me and it became an intimacy that I cherished. Then I went into the world of producing, of all things. I went from black and white. I went into producing a daily live 90-minute broadcast, if you can believe it. I mean, I dropped into the deep end of the pool. And I remember after getting into the buzz of all of that, I remember at some point coming back to my studio and just weeping because I missed the intimacy with God, I missed the quiet. And somehow for the first time in the last few days, that came back to me that there is blessing in this slowdown. There is something. Now I’m not somebody who has little kids who need to be entertained. And I can’t even compare my life. I mean, I have this maybe good fortune, bad fortune of having that kind of quiet. But it’s interesting because I think there is the possibility of a reset, but I think the reset is not going back to something it’s not going back to my studio, but is entering into what God is offering me now. And it is obviously a profound moment to decide, will I seek the face of God? Will I seek intimacy with God? And recognizing what you have shared and what Henri found that that father, that God image is so welcoming and so willing to take us home. And ultimately we have the power to become that to the world that is counting on hearing from us.

Gabrielle: Yes, but I’m sharing some of that. I too don’t have young children who are needing all of my attention. And I think that the word loneliness – a lot of people are feeling lonely and isolated and Henri has a book called Reaching Out – a very early book. And one of the chapters is the movement from loneliness to solitude. And I think that some of the wisdom in that book is applicable here too. I mean, we can see our lives that have become much smaller than they usually are. We have a lot more alone time, a lot more time to fill. Some people are finding it hard even to fill all of the hours of the day. But can we convert that, can we see this as a moment of conversion from loneliness to solitude? So solitude is where we are. I think in Henri’s way of understanding it, we are in the presence of God like you’ve just said. And that we’re not alone and lonely, but we are alone and in the presence of God. And that we can in time and perhaps when this pandemic is over… And in fact I’m already anticipating a little bit of how hard this might be for me because I have so much time now to be in the presence of God, carving out the time, will my life fill up again and will I then again start to just being busy and distracted? And I think that in a way, this pandemic is asking us that question. When it’s over, how will we be? And we’re being asked that individually, as well as a society, as a world. What do we want the world to be like when this is over? How do I want, what do I want to be like when this is over? And I think one way of being creative with this time, and you know, we’ve got a lot more time to be attentive to the people in our lives. We’ve got a lot more time to be attentive to the beauty all around us and appreciation for the beauty of the earth. And I hope that some of those things will be what we’ll be able to carry forward.

Karen: Thank you, Gabrielle, I always love interviewing you. You are so full of ideas and you bring a depth of insight into the writings and teachings of Henri Nouwen. But beyond that, I really love your honesty.

Gabrielle: One thing that I wanted to make sure I spoke about because I think it’s a really important part of the book and I think it applies to us. You’ve already mentioned gratitude, the discipline of the practice of gratitude and how important that is in order to be loving people, we need to be grateful people. And another thing that I think you’ll appreciate too, as a way to end this is the way that Henri speaks about the importance of celebration. And the reason why I think it’s so important to mention is because a lot of us would think that this is the very last moment that we need to be celebrating. You know, we’ll celebrate when it’s over, we’ll celebrate when we’ve got a vaccine. But Henri is saying the exact opposite. And I wondered if I could just read a passage from the book that I think might be a source of hope and possibly inspiration for people. Would that be okay?

Karen: Please, please do it. Yes.

Gabrielle: So it’s on page 108. He says, I don’t have to wait until all is well, but I can celebrate every little hint of the Kingdom that is at hand. This is a real discipline. It requires choosing for the light, even when there is much darkness to frighten me; choosing for life, even when the forces of death are so visible and choosing for the truth even when I am surrounded with lies. I am tempted to be so impressed by the obvious sadness of the human condition that I no longer claim the joy manifesting itself in many small but very real ways. The reward of choosing joy is joy itself. Living among people with mental disabilities has convinced me of that. There is so much rejection, pain, and woundedness among us, but once you choose to claim the joy hidden in the midst of all suffering, life becomes celebration. Joy never denies the sadness, but transforms it to a fertile soil for more joy.

Karen: Oh, that’s beautiful. Thank you, Gabrielle. This has been so interesting.

Gabrielle: You’re welcome.

Karen: In the weeks to come, I look forward to interviewing Gabrielle again because she has a new book coming out called Return of the Prodigal Son: The Making of a Spiritual Classic. This book gives us wonderful biographical insights into Henri Nouwen insights that I’ve never been aware of before. The book will be launched on May 12th so watch for it. And be sure and join us when we do a podcast exploring the contents of this great new book by Gabrielle Earnshaw.

Thank you for listening to today’s podcast. For more resources related to today’s program, click on the links on the podcast page of our website. You can find additional content and book selections. Thanks for listening, until next time.

In the words of our podcast listeners

Sign Up for Our FREE Daily Meditations & Newsletter!

Help share Nouwen’s spiritual vision

When you give to the Henri Nouwen Society, you join us in offering inspiration, comfort, and hope to people around the world. Thank you for your generosity and partnership!