-

James Martin "Jesus, A Pilgrimage" | Episode Transcript

Karen Pascal: Hello, I’m Karen Pascal. I’m the executive director of the Henri Nouwen Society. Welcome to a new episode of Henri Nouwen, Now and Then. Our goal at the society is to extend the rich, spiritual legacy of Henri Nouwen to audiences around the world. We invite you to share these podcasts with your friends and family. Because we are new to the world of podcasts, taking time to give us a review or a thumbs-up will mean a great deal to us and will help us reach more people.

This week, I have a wonderful guest with me, Father James Martin. Father Martin is a Jesuit priest, editor-at-large for America magazine, and author of several bestselling, award-winning books, including The Abbey, The Jesuit Guide to (Almost) Everything, Between Heaven and Mirth, Building a Bridge, and Jesus: A Pilgrimage. Father Martin frequently provides commentary in such places as the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal, and on all the major television and radio networks.

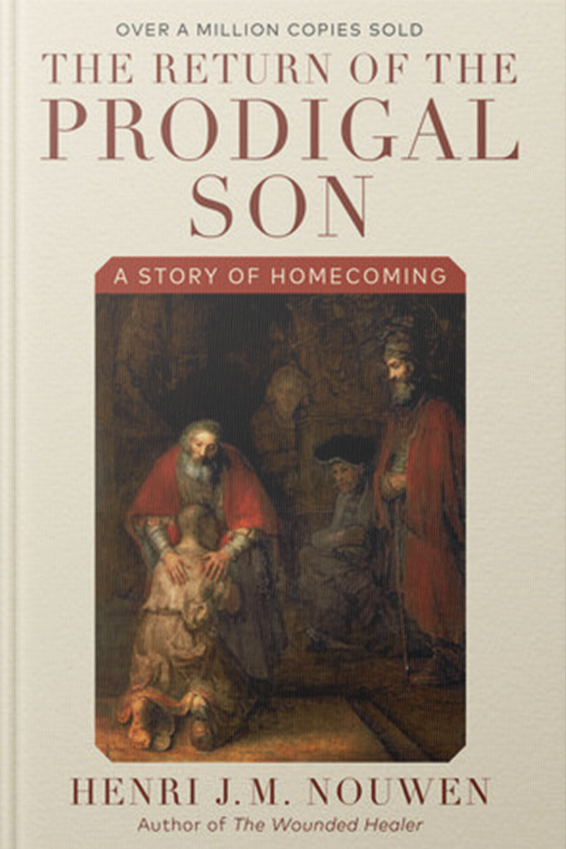

Jim, it’s so good to have you with us today. You wrote the foreword to the anniversary edition of The Return of the Prodigal Son. In this, you say, “The most arresting feature of this book is for me, the author’s near-total candor.” Tell me a little bit about what that book did for you.

James Martin: Well, I think it’s one of the greatest exegeses, or opening up of scripture, that I’ve ever read. I think that his ability to take that one story and dive deep into it and open it up for us, and also be honest about, as he is in all of his writings, as you know better than anyone, his own struggles, his own failings, his own neediness at times – I think really cements his relationship with the reader. And frankly, when I write, he’s one of my models – him and Thomas Merton, but especially Nouwen – in his openness. And I think that just draws you in and it makes you want to trust this person and also go along with this person. But frankly, I think that the message of that book, I think whenever I preach on the prodigal son, I always use and I always quote Nouwen’s insight, which is that we act like the younger son, we feel like the older son, but we should be living like the father. That’s for me, that’s the book in a sentence, but I think it’s just a brilliant book, frankly.

And I’m writing my own book on Lazarus and I’m using his book as a model, right now. What he did for the prodigal son, I’m trying to do for Lazarus.

Karen Pascal: Oh, that’s fantastic. I mean, I am loving your books and loving your social media posts as well. So, it’s neat to hear you talk about that and about how Henri has influenced your writing. Did you ever meet Henri, by the way, or have you just got to know him like most of us got to know him – through his writing?

James Martin: Through his writings. You know, I know a lot of people who knew him. I entered the Society of Jesus in 1988. And that’s when I first got interested in his writings and I really can’t pick a favorite book. I think for me, The Genesee Diary was the one that opened me up to him. And again, as you know, he’s so honest in that book about wanting to, in a sense, get away from the hustle and bustle of his life and then finding himself in the monastery and then feeling lonely and, you know, do people need me? And that’s really hard to talk about. In fact, even my mother. . . it’s funny: I’ve spoken enough about Nouwen, and when I go on retreat, she’ll sometimes say, “Well, are you’re going to be lonely like Henri Nouwen was?” So, that honesty even penetrated our relationship, you know, with my mom, that in other words, that insight that he had really made a profound effect on her.

Karen Pascal: It’s funny, because I think The Genesee Diary was the one that really broke through to me, too. It was quite profound. And you mentioned something which I loved in your foreword to The Return of the Prodigal Son. You mentioned that he actually, within the book, says that he wants to be remembered after he’s dead. And it’s interesting, because I think probably that book more than any other is probably what he will be remembered for. But there’s this big body of work, and it has been so life-giving for all of us. We kind of live in the wake of Henri and that daring honesty and kind of bared-soul reality, that we all go, “Oh, that’s me, too. That’s me, too.”

James Martin: Well, that’s right. And as I say, I pattern, consciously, my writing style on his, because I don’t think, I’d really never read a spiritual writer who – I mean, I’m sure there are others, obviously, all the way back to St. Augustine – but who shares some of the embarrassing things, too. His relationship with – who just died, I think, Dom John Eudes Bamberger – who is his spiritual director in The Genesee Diary. You know, where he wonders, “Is he mad at me? Does he like me?” That kind of need to be liked, I think, is something that runs through Nouwen’s books, which I think everyone can kind of connect to. And he has encouraged me, through his writings, to be honest in the spiritual life, even about the embarrassing things, because most spiritual writers say, “Well, I had this problem and I triumphed over it,” right? And, “Aren’t I holy and aren’t I spiritual?”

And that’s not the sense you get from his writing. He’s still, for example, even at the end of The Genesee Diary, kind of struggling with those feelings of worthiness, likability. So really, very, very universal things for people to look at.

Karen Pascal: Now, one of the things that I’ve been catching from you in the last weeks has been your take on the pandemic. Life got turned upside-down for so many of us and for everybody, for the world. We’re united with the world in this. There you are in the middle of Manhattan; how’s it going? What’s working for you? What kind of spiritual practices are working for you, or just, how are you doing life right now?

James Martin: Well, you know, I’m luckier than most people; I’m not sick and my mom, who’s 88, is not sick, and our Jesuit community has not been sick. But there’s been a lot of Jesuits that have been affected and have died. I know, for example, in Pickering in Ontario, there were many Jesuits who died. In the infirmary at St Joe’s University in Philadelphia, we had six Jesuits die. I live around the block from and as I’m speaking, I can see the windows of, Mount Sinai Hospital in New York, where there are people dying and sick. And so, while I’m quarantined at home, obviously, and working from home, I’m healthy so far. But I find that just taking it day by day is the most important thing. I don’t think you can sort of get into the what-ifs. I mean, we all have to take precautions, obviously, and be careful about not spreading the disease. But what if this continues for the next year, or two? I think just taking it day by day is very important, and just being centered and grounded in the present.

Karen Pascal: It’s interesting, because I think sometimes people take on this agenda in their head, like, “I’ve got to accomplish so much, I’ve got a different availability,” but there is something that really. . . I’ve found myself saying it’s like a malaise. It’s sometimes hard to lift the cloud. And I can’t help but wonder what is going to be different after this. Do you have thoughts about and longings for what might be in the future after this?

James Martin: You know, that’s interesting. I hope something is different. But you know, human nature is such that we tend to want to forget these things. I remember reading an article recently about the Spanish flu – and I don’t know if you can call it that – the flu in 1918, where there was very little written about it and people were consumed with the war, World War I, and they wanted to just get on with things. And so, if you think about it, there’s very little in our culture that talks about the flu from 1918. You know, I hope that people learn, as Pope Francis said, it’s not God’s judgment on us, it’s our judgment on what’s important: family, friends, life. I do think it is exposing the inequalities. You know, the people who are. . . beyond the doctors and nurses and healthcare workers, you have people like grocery clerks and transit workers who are kind of forced to go to work, to make things continue. And it’s kind of a disparity between the rich who can stay at home and the poor who cannot.

But truly, I hope we do remember these things, because I think we tend to just move on, and it’s difficult for us to contemplate not only these difficult questions of inequality in healthcare, but also difficult questions of powerlessness. I think that, in the West, we’re very reluctant to say this is something that we are. I mean, we hope that there will be a vaccine, but we are currently powerless over this. The German – I think he’s German – film director, Werner Herzog talked about nature’s “monumental indifference.” And I think that’s something we’re uncomfortable with.

Karen Pascal: I would agree with you. I mean, it has underlined the inequities and it does give us pause to really think, how do we want it to be different? Because we have to be part of the wanting it to be different. It won’t just automatically happen. We have to kind of lift up the banners of what we believe in, and move them forward.

James Martin: Well, that’s right. And also, you know, I remember 911. I was here in New York City in 2001, and people said then, I remember it, “Everything will change. Everything will change in the city, everything.” And you know, not a whole lot did. I mean, the area around Ground Zero changed, of course, and we went to war – that changed, but I didn’t see a huge shift in the culture in New York City, where people became more kind and friendly. You know, Gore Vidal, the American writer, talked about the United States of Amnesia. We tend to want to just forget, and move on. So, I really hope that we do take these things seriously. But, you know, like in every person’s life, if a tragedy comes, some people may reflect on it and learn from it and take some sort of meaning from it and see God in it, and some people won’t, right? So, it depends.

Karen Pascal: Now, I’d love to talk about a couple of your books, because I’ve just really been enjoying them. The first one being Building a Bridge, which I think is a great book and obviously must have ruffled feathers, but must have also delighted some people. I know you originally wrote this for the LGBT Catholics and for church officials. Tell me a little bit about the response and tell me a bit about who really has embraced what you’re saying here and just take us there with – it’s a wonderful book.

James Martin: Sure. Thanks. So, it’s about the church reaching out to the LGBT community. And it came in the wake of the Pulse nightclub massacre in 2016, where I felt that the church really barely expressed their sympathy. You know, when 49 people were killed in this gay nightclub (or largely gay nightclub). And the book was initially, well, it was supposed to be very modest and it initially was a very small book. There was a second edition that came out and I was shocked at the reaction, both positive and negative. The positive reaction, you know, far outweighed the negative reaction, but huge crowds, 700, 800 people in packed parishes, standing ovations, people hugging me, crying. And I thought, well, this is really surprising, because the book is pretty modest. It doesn’t challenge any church teaching. It just basically invites people to treat LGBT people with respect, compassion, and sensitivity.

But I think that the conversation apparently needed to happen. And then, the backlash happened, which was a lot of personal vilification, you know, attacks on me personally, online mainly, protests and name-calling. And I’ve been called every name in the book, truly. It was like you felt like you were on a junior high school playground. And then what I would call the pushback to the pushback. Then I had people like Cardinal Cupich, Archbishop Gregory inviting me to speak. You know, I got invited to the World Meeting of Families, and then last September, Pope Francis invited me to a private audience in the apostolic palace. And so, that was kind of the ultimate, the ultimate pushback to the pushback, you know, which left me completely inspired. And, you know, he was very supportive. I’ll just leave it at that.

Karen Pascal: Oh, that’s so good to hear. I’m just delighted to hear that. You know, you conclude that the book is about dialogue and prayer. Do you think it’s helping and what do you think, are you going to write another book? Are you going to take it farther? I’m curious: Where are you going to go with this?

James Martin: Well, you know, I think I said my piece in that book. And it is about dialogue, both – I don’t like to call them sides, but there’s the LGBT community and the church, because LGBT Catholics are part of the church – I think it is helping. I think the Pope’s invitation to an audience, that word got all over the world; there were photos sent out. And I think that gave a great boost to LGBT people. Look, I’m not saying this is as a result of the book, but two years ago, even using the word LGBT in some circles was considered too much.

So, there’s two things that are going on, not definitely related to the book. Number one, Pope Francis is simply putting in more and more cardinals, archbishops, and bishops who are open to that community. And number two, more and more people are coming out. And as they come out, they bring those desires and joys and struggles into their families and then into their parishes. And that affects dioceses, and that affects the church. So, even if the first trend stops, if Pope Francis, God forbid, if he dies tomorrow and he stops appointing people, the second trend, which is more and more openness in society, is not going to stop.

Karen Pascal: Absolutely. It’s really interesting. I loved where you began it, when you talked about when you’ve been received in baptism, you’re a member of the church. Period. End of story. And I love that.

James Martin: Thanks. Yeah. I always say to people who feel that they’re being in a sense pushed out of the church, LGBT people: “Look, you’re baptized. You are as much a part of the church as me, as your local pastor, as your local bishop or Pope Francis. Period. I mean, you’re a baptized Catholic.” The End.

Karen Pascal: Well, let me ask you the question. Now, the book didn’t go anywhere near some of the really rough topics right now, like the clergy sexual abuse. You didn’t go there. Why not?

James Martin: Well, mainly because the book wasn’t about it, that topic. It was about the LGBT community. And I certainly didn’t want to bring it up, because that equates, in people’s minds, homosexuality with pedophilia, which we know is false. You know, because you’re gay, you’re not a sex abuser. I mean, I talk about it a little in the book, but I also didn’t want to bring it up, because I think any sort of introduction to that very complex topic, the causes are so complex, right, about those crimes. I think to bring it up and just mention it, or bring it up in a sort of incomplete way, would’ve been almost insulting to people.

And it just wasn’t about that. But, really, again, there’s this false equation. A lot of people who are homophobic say, well, you know, if you’re gay or if you’re a gay priest, even if you’re celibate and chaste, as you know, gay priests are supposed to be, like straight priests, then therefore you’re a child abuser. Which is baloney. So, I bring it up in that sort of vein, but to go into this sex abuse crisis, which I’ve written about elsewhere, I thought was kind of not part of that book’s scope; it’s a very short book, too.

Karen Pascal: I take it that it started out of a talk and then it was just such a hit that it needed to be out there. It really needed to be out there, which I’m glad you did it. I’m really glad that you did it.

Now the fun for me, because I said, “Well, what are we going to talk about?” And you said, “Well, what about Jesus: A Pilgrimage?” Which is just a fabulous book. I have to tell you, though, given the COVID shutdown of everything, I went after getting the book right away. I should have done it as an audio book and I would’ve been able to download it or download it on Kindle, but instead I sent for it. It arrived at four o’clock yesterday afternoon. And it’s close to 540 pages. So, I can’t tell you I’ve read the whole book, but my gosh, I really enjoyed what I got into. And I was even reading in the middle of the night. I was really enjoying it. I love what people write about it. They say, it’s an infectious travelogue, spirituality, theological reflection, combined with wit and human insight. That’s from the Tablet.

And it’s funny, you really surprised me with the book, because in a way, you got me from the beginning, I had the same, unique experience. About eight years ago, I went to Israel and did a four-part documentary series called Journey to Christmas. And it was profound for me. We had a wonderful spiritual guide who took us into the story behind everything. So, last night as I got into your early chapters, which are about Mary’s “yes,” and then Bethlehem, and then Nazareth. I’ve been there, and it just was so alive to me. But I found it just such an insightful, interesting book. I really can imagine you’re not the same after having had that trip.

James Martin: Oh, absolutely. I’ve led five or six pilgrimages since then. And I always tell the pilgrims, this is going to change your life, because at the very least, you’re never going to read the gospel stories the same way again. You know, names like Capernaum, where people think, oh, whatever. Then when you’re there and you see where it is and what it was like and how long Jesus spent there and how many miracles he did there, you think, “Oh, my gosh.” And so, when you hear the word Capernaum again, you’re sort of brought back there, and it really sort of grounds the gospels in a way that’s hard to describe. But I just had fun. Now, I think, people who are listening, they say, “Oh my gosh, because of time, health, money, fear, I’ll never go there.” And that’s one of the reasons I wrote the book: to give you this experience of being there and being on pilgrimage and finding new things about the gospels. You know, I just love learning about the daily life of Jesus. It’s fascinating to me, endlessly fascinating.

Karen Pascal: Well, the book had to me a really special charm, because I just constantly felt your sense of, “Wow, Jesus walked here. Wow, this happened here.” And I’ve felt exactly the same thing. And you know, what a privilege that we both had that experience, and it’s wonderful that you’ve been able to share it with others. It’s interesting, because my Journey to Christmas brought together four people that we took with us. One was an atheist; one was a Jewish fellow; and two of them were at different stages of Christian faith. So those four people were kind of taking a look at this and trying to figure out what’s here for us. And there were some wonderful discussions in it. But out of it, I thought, okay, I want to do Journey to Easter. And I never got to do that. But nevertheless, I mean, I come back and I think there’s something about understanding that the story is real. The story is real.

James Martin: Well. Yeah. I’m sorry. Did I interrupt You? Sorry.

Karen Pascal: No, no, you didn’t. No, no, no. Just that, it connects Jesus to a land, to a place to a . . . yeah. And I was going to say, I love what Harvey Cox, the professor at Harvard said. He said, “Do we really need yet another book about Jesus? If the book is this one, the answer is yes.”

James Martin: Well, and you’re right. And you know, when people go there, when I accompany pilgrims there, they almost, someone almost always says, “I’ve always believed in Jesus.” You know, these are very faithful Catholics. “I knew that there was such a thing as the Sea of Galilee, but I always thought, part of me always thought it was almost like semi-mythical.” And then you see it and you say, this is clearly . . . There are a few places you can stand, and one of them is on the Sea of Galilee. And you can say, without a doubt, Jesus saw this. Jesus himself saw this view. And it’s amazing. I’m getting goosebumps right now, just thinking about it. It’s amazing to think that, and again, it makes him real for people. A friend of mine, before I left, said that it was also like visiting a friend’s home and family. You might think you know your friend really well, but if you go to the friend’s home and you see where they grew up, it just opens things up for you in a brand-new way.

Karen Pascal: Yeah. You get the context of this is where they were shaped and formed. I followed you as far as I got into the book into the middle of the night. I followed you and went, “Oh, I know I’m going to finish this,” because it’s just quite delicious. But I do feel kind of like a companion to you on the trip, because as you get really into the details of the place you’re looking at, it brings back to my memory some very moving moments. I just found it was like a pivot point for me, as well. It was quite special.

James Martin: Yeah. Well, most people, they’re not the same after that. As you know, that’s one of the reasons they call the Holy Land, the fifth gospel. It’s coming and having an encounter with, in a sense, the story told, in a different way. And so, for example, when you see even just the distances, so you see, well, Jesus went from Nazareth to the Sea of Galilee, and in your mind, you say, “Well, that’s nice.” Then when you see how long it takes through a valley that’s very rocky and over mountains and cliffs, and you say, “Oh! Okay.” Or when Jesus’ family, in Mark, chapter three, come to restrain him, because they’re so worried about him and they think he’s crazy. You see, well, Mary and his extended family walked that way just to – how frustrated and upset must they have been with him, right? It just deepens it for me, and it deepens it for anyone who’s been there. And that’s what I try to do with the book: to really deepen that experience for the reader.

Karen Pascal: I found that it was so accessible. You had the guides telling us about the locations, you had great theological insights, but then there’s this very personal revelation from your own heart. It really, truly is a pilgrimage, and you really, truly are giving us, too, what you got in that moment. And there’s an immediacy to that. And I would just recommend the book for everybody. I just think you’ll so enjoy it. I mean, it’s really a good book.

James Martin: Well, I’ll bring it back to the beginning of our conversation. A lot of that comes from Henri Nouwen. And so, I think had I not read people like — other ones, of course, Henri Nouwen, Thomas Merton, I would point to also Kathleen Norris, who’s a big favorite of mine. If I had not read spiritual writers like that, but especially Nouwen, the book would’ve been just theology and travelogue, right? But the third part, which is spirituality and my own experiences on that trip, that’s Nouwen. I mean, that’s where that comes from. So, it’s like the prodigal son: He could have easily written a book about. . . or Genesee Diary. He could have easily written a very dry book about what it is like to be in a monastery, or what this parable of Jesus’s says to us today. And that would’ve been fine. You know, he could have talked about theology and, in the case of the prodigal son, he could have talked about theology and scripture, but it’s the added part of his own life. And then, in The Genesee Diary, it’s not just: Here’s what it is like to live in a monastery. It’s: Here’s my experience and my struggles. And that frankly is the most, I think that’s the most important part of both books.

Karen Pascal: Ron Rolheiser has been really a leading expert on Henri. And it’s interesting, because one of the things he talks about is that really, Henri gave us the language of spirituality. I think that’s really interesting. He talks about, there was a time when that didn’t exist in quite the same way. I find that fascinating to think that that may be one of his big contributions.

James Martin: I think that’s really interesting to hear you say that, because I am not a scholar of spirituality, and so I trust people like Ron Rolheiser. I think that’s why, I’ve always had that intuition that it was him, you know, because it is true. I mean, before, if you read, obviously, Thérèse of Lisieux talks very openly about her struggles and Dorothy Day does, but there’s a kind of . . . again, I think it’s stuff that he reveals, which is kind of embarrassing things, right. I mean, Dorothy Day in her diaries does that, but not in the books that she had published before she died. And I think that’s accurate and I think that’s the kind of spirituality or spiritual writing today that attracts people. Now, some people don’t like it; some people hate it. Oh, it’s all about you or it’s too solipsistic or too egotistical. But I find it really draws people in, it just does. Now, I think you have to strike a balance, because it can’t all be me, me, me. But it’s not, in his books. It’s always this kind of narrative theology. It’s for a purpose; it’s to help the reader.

Karen Pascal: Yeah. Tell me, what are the projects you are working on now, by the way? What have you got on the go?

James Martin: Yeah, well, I just finished a book, we’re looking at the covers now, called Learning to Pray, which will be out, God willing, next year. It’s called Learning to Pray: A Guide for Everyone. It really is a guide to prayer from soup to nuts. And I always say, I like to think about giving these books to people who know nothing about, for example, Jesus or Ignatian spirituality or prayer, in this case. And then I’m writing this book on Lazarus, the raising of Lazarus. And really, my model is The Return of the Prodigal Son, which is to take a part of scripture that is rich and that appeals to me, and really open it up. I’m doing a little bit more scripture analysis than he would’ve done in the prodigal son, which takes off, as you know, from the painting and the story itself. But that’s my idea. As he did it for the prodigal son, I’m going to try to do it in my own way – not sort of comparing myself to him – with the raising of Lazarus, which is, I think, my favorite gospel story.

Karen Pascal: It’s interesting. Somebody shared something with me that just really struck a note with me about that story. And it was: Why was Lazarus at home with his sisters, wondering about whether he might have been perhaps developmentally delayed. He might have needed those sisters to care for him. And I was so touched by that. That to me was really significant. I don’t know where you’re going to go with it, but I know for me, I thought he loved Lazarus and that meant a lot. You know, who was this person that he loved?

James Martin: Yeah. And especially, you think about Henri Nouwen’s book, Adam, right, and his relationship with the L’Arche community. But I had heard that, I could talk about that for an hour now. But Lazarus, as you said, he’s with his sisters, first of all. And also, it’s called the house of Martha and Mary. It’s, “Jesus went to Martha’s house,” not Lazarus’s house and not their father’s house. And also, Lazarus has no lines. Lazarus says nothing in the gospels. Why is that? And that, as you say, one of the thoughts is that he may have been in some way disabled.

The other insight, which is fascinating and which sort of blew my mind, and I hope blows your mind, is that many scholars today believe that Lazarus is the mysterious “beloved disciple” in John’s gospel, who is the sort of origin of the story that we find in John’s gospel. And it is not so out-there, if you think about it. He is called “he whom you love.” The beloved disciple is the one whom Jesus loves, and there are many little clues at the very end of John’s gospel, which I find fascinating. You remember in John 21, when Jesus meets Peter by the seashore, and he says, “Do you love me? Do you love me? Do you love me? Feed my sheep, feed my sheep.”

At the very, very end, there’s this very strange passage where Peter turns to Jesus and says, “What about him? Is he going to die?” about the beloved disciple. And most people say, “Oh, that’s interesting.” Well, who would they say that about? Why would they expect some fishermen from their group or a tax collector to never die? They would probably say that about Lazarus. Is he going to die again?

Yeah, exactly. And so, there’s lots of little clues like that. So, Lazarus: Yes, he may have been disabled or may have been the beloved disciple or may have been a leper. That’s the other thought: that Mary and Martha and Lazarus were all lepers. They had leprosy, Hansen’s disease. So anyway, I’m trying to do what Henri did for the prodigal son. If I get halfway there, if it’s halfway as good as that book, I’ll be very happy.

Karen Pascal: Well, I find it delightful to see, like, who would’ve thought Jesus: A Pilgrimage would be on the bestseller list of the New York Times? But you write in such an accessible and such an engaging way. And I’m sure that the next one will be very much the same. I do need to ask you one thing. There’s another part of your writing life, you’re editor-at-large for America magazine, and that’s such an important magazine. Tell me just a little bit about what does it mean to be editor-at-large in that context?

James Martin: Well, my joke is, I can write whatever I want to write. So, because I took a vow of poverty as a Jesuit, as a member of the Society of Jesus, all of my earnings, whatever, everything goes to the Jesuits. So, for example, when I get a paycheck from America, it goes to my community. But the royalties from my books all go to the magazine. And so, that’s kind of my work, which is to write books and also bring in money and give talks and things like that. So, I’m an editor, like every other editor. I don’t edit articles anymore, I can say, thank God. But I’m in the office every day, or at least I was, and I write articles, work with the staff, and I love it. I hope I never leave. I really love writing, love it, love it, love it, just really love it. And so, there’s this prayer book and then the Lazarus book.

Karen Pascal: There are good things coming.

James Martin: There’s a lot of things coming, yes. I have a lot of plans. Hopefully I’ll be able to accomplish some of them.

Karen Pascal: Well, I kind of know there’s good things coming, too, because every so often, I send out an invite to you and say, would you come for this or would you come for that? And then, you’re careful with your time; you are making good decisions about your time. And I think that’s an interesting thing to note, too: what to say yes to; what to say no to. But it’s interesting to hear much how much you love writing. It shows on the page. It really does show.

James Martin: Yeah. Thanks. And part of it is also, I know that if I travel, I can’t write. And of course, who knows what travel’s going to be for the next year or so. But I have a little carpal tunnel, so I have to be careful about how much I write, physically. But frankly, if I could write all day, truly, I’d be happy. I mean, I realize some people hate it, but I love it. I just love It.

Karen Pascal: I fear the blank page, but I’m glad to know somebody out there loves it. I am so glad to hear that.

James Martin: Oh, no. Look, I always say, my advice to people is always to say to yourself, “What do I want to say?” That’s all. And then just say it. And the other thing is, if you’re worried about saying the best thing or writing the best way, someone said to me, “The greatest cure for writer’s block is this: Immediately lower your standards.”

Karen Pascal: That’s perfect. That will help me. That will help me. I find that the whole business is just, “put something on the page,” and I always think it’s awful. But the next day I look at it and I go, “That wasn’t too bad. We’re going somewhere with this.” I think I find that helpful.

Can I ask you something, sort of in a closing question? You have said some wonderful things about Henri Nouwen, but one of the things that I, in a sense, in this role as the executive director of the Nouwen Society, we long to share what Henri has to offer with the next generation. But really there is a question: Is Henri needed at this time? Are there things that you feel Henri has to say that don’t come from anywhere else? Or, just let me hear a little bit from you on that.

James Martin: Oh, yeah. I still think what Rolheiser said is important, which is that he is the, I would say, the groundbreaking voice in Catholic spirituality, after Merton and Dorothy Day, who didn’t write in his style. I mean, they simply didn’t. Thomas Merton in his diaries, he’s open, but not as transparent. And I think young people really crave that sense of authenticity and honesty.

And I also think his emphasis on people who are forgotten in society, right? I mean, Adam, for example and some of the insights he has from his work in L’Arche is really helpful. I find that voice so appealing. So, for example I used to run a book club at the Church of St. Ignatius Loyola, the Jesuit church in New York City. And we would read Thomas Merton, The Seven-Storey Mountain, and we would read The Long Loneliness by Dorothy Day, two of my heroes. And Dorothy Day’s on her way to sainthood, and should be.

And I’ll tell you: Some of the young people didn’t like them. They didn’t like Merton, because he could be pretty full of himself, right, especially at that time in his life. Dorothy Day, they found the book too long and she’s extremely cerebral. And you know, Nouwen was very bright, too. They all loved The Genesee Diary. They loved it; so, there’s something about that voice that I think speaks to young people, especially today. It’s honest.

I think people trust him, in a sense. He’s not as sort of forbidding, I would say also, as Dorothy Day and Thomas Merton.

Karen Pascal: I think probably one of the things that I found so, in a way, endearing, is he keeps taking us down another level inside of himself. And he does it within us, as well. And it is that issue of self-loathing, which I went, “Oh my goodness. Somebody just talked to some very deep places in my secret being.” The self-loathing issues and things like that, that he had words for. And you go, “Oh yeah. Oh yeah, that’s me.”

James Martin: Well, and he is also a psychologist. And so, you trust him in that sense, too. It’s not simply someone flailing around and throwing out insights that may or may not be helpful. I mean, this is someone who has a very deep, psychological background and psychological training and also spiritual training, so you trust him, too. Right? I mean, not everyone has to have a degree to be trustworthy, obviously, but I trust him when it comes to the psychological stuff. And also, I also knew people who knew him. Did you know him yourself?

Karen Pascal: Yes, I did. I did. I did. I actually have a story where, in essence, I pursued him. Once somebody gave me his books, I pursued him. I was doing a program at the time called Cross Currents, which was kind of a round-table forum. And eventually I got to bring him to the program, where we went to him. And then ultimately, he died a year later. And then I realized I had some of the best material on Henri. And that’s when I started doing the documentary, Journey of the Heart: The Life of Henri Nowen. But I really, in a way, got to know him through his friends, as opposed to . . .

James Martin: Now, I’m curious. I’m sorry; go ahead.

Karen Pascal: Yeah, no, I was just going to say, I got to know him through his friends, his family, his colleagues, in a sense. Sometimes you do a documentary and you are telling the story you believe you know. But in this instance, I felt like I was framing a story that they knew. They had loved and lived with him and got the good and bad of him. And so, Journey of the Heart really brings together that account. We have that on our website, and anybody can download it if they want to know, in a sense, Henri’s story. It’s there.

James Martin: Now, how would you describe him, if you were to describe him to someone who didn’t know him? What would you say? What was he like in person?

Karen Pascal: I think he was a very intelligent, energetic, needy, wonderful . . .

James Martin: I’ve heard that word. I’ve heard that word a couple times about him from friends.

Karen Pascal: Yeah. Needy. Wonderful. One of the things that I saw in Henri as I kind of pursued him, was how he was always learning, how there was always something new. And I kind of hear that in you. I mean, you’re writing something new. There’s always something you’re pursuing. You’re not sitting back. I mean, anybody who writes 39 books or 40 books has . . . Sometimes I’ve said, “Did he write the same book over and over again?” But he didn’t, really. He was growing, he was moving forward in his life, I think. And he was in the process of solving all the things that had held him back.

It’s funny, because some people say, “Should he be sainted?” And then I hear other friends of his say, “The people to get sainted are the ones who drove with him,” because he wasn’t, you know, if you survived that. . .!

James Martin: In the Jesuits, we have an expression: the saints and the martyrs; the martyrs are the ones that have to live with the saints.

Karen Pascal: I think so. He could receive from others, and you captured that, I think, just in your foreword to The Return of the Prodigal Son. Clearly, Sue Mosteller was a person who, in her letters and in her presence in his life, pushed him forward to understand God was calling him to be the father. He could be the prodigal son. He could be the brother. But eventually, that call that calls to all of us that we might welcome people home. And I remember one of my most precious memories, it’s just engraved in me, was him talking, saying, from the father’s perspective, “I’m so glad you’re back. I’m so glad you’re back.” And the fact that the father doesn’t say, “Where have you been? What were you up to?” It’s just, “I’m just so glad you’re back.” And that kind of a welcome is, I think, what probably we hope that young people who are looking for something will hear: “I’m so glad you’re back.”

James Martin: That’s a great insight. I think everybody needs to hear that. True. Exactly. It’s beautiful.

Karen Pascal: The other thing I would say, I’m going to encourage everybody: go out and buy some of these wonderful books. If you haven’t read James Martin, check out his social media podcasts, they’re great. But I’d also really encourage you – I mean, who would’ve thought Jesus: A Pilgrimage would be a bestseller on the New York Times bestseller list. But it’s really because it’s such a delicious book and it’s funny and it’s honest. And I just would encourage them.

Thank you, James, for giving me the time today. It’s really been a pleasure to talk with you. You’re one of the people I enjoy and watch and listen for. So, I thank you for being such a rich gift to us at the Henri Nouwen Society.

James Martin: Thank you. It’s been my pleasure and delight to talk with you, and thanks for all the great work you do there.

Karen Pascal: Oh, thank you. Good. Have a great day. Have a great rest of the day.

James Martin: All right. Take care. God bless. Bye-bye.

Karen Pascal: I hope you come away from this interview with Father James Martin as inspired and moved as I was. I look forward to finishing his book, Jesus: A Pilgrimage, and I’d encourage you to get this as well.

If you enjoyed today’s podcast, we’d be so grateful if you take time to give it to a stellar review or a thumbs-up, or even share it with your friends and family. As well, you’ll find links in the show notes for our website and any content resources or books discussed in this episode. There’s even a link to books to get you started, case you’re new to the writings of Henri Nouwen.

Thanks for listening. Until next time.

Sign Up for Our FREE Daily Meditations & Newsletter!

Help share Nouwen’s spiritual vision

When you give to the Henri Nouwen Society, you join us in offering inspiration, comfort, and hope to people around the world. Thank you for your generosity and partnership!