-

Steve Bell "Songs, Stories & Sacred Traditions" | Episode Transcript

Karen Pascal: Hello, I’m Karen Pascal. I’m the executive director of the Henri Nouwen Society. Welcome to a new episode of Henri Nouwen, Now and Then. Our goal at the Henri Nouwen Society is to extend the rich, spiritual legacy of Henri to audiences around the world. Each week, we endeavor to bring you an interview with someone who has much to share from their own spiritual life and work, and who has been deeply influenced by the writings of Henri Nouwen. We invite you to share the daily meditations and these podcasts with your friends and family. Through them, we can continue to introduce new audiences to the writings and teachings of Henri Nouwen, and remind each listener that they are a beloved child of God.

Now, let me take a moment to introduce today’s guest. Today on this podcast, I am joined by my good friend, Steve Bell. Steve is a songwriter, storyteller and troubadour for the challenging times we’re living in. Since 1989, Steve has produced more than 21 solo CDs, received numerous awards and acknowledgement for the excellence of his work, and he’s performed with full symphony orchestras on nine occasions. Home base for Steve is Winnipeg, Canada, but Steve has performed in over 2,000 concerts, to more than half a million people in 15 different countries of the world. Steve can well be described as a purveyor of truth and beauty and a champion of kindness. Through his writing, he aims to encourage Christian faith and thoughtful living inspired by his music.

Steve, you’re one of my very favorite singer-songwriters. And in these last few days, as I’ve been preparing to talk with you, I have been immersed in your writing. You’re a deep soul with a wealth of thoughtful and profound insights.

Listeners, you’re in for a treat. This man has so much to share with us.

Welcome, Steve Bell, to Henri Nouwen, Now and Then.

Steve Bell: Thanks, Karen. It’s such an honor. I really appreciate it. This is fun for me.

Karen Pascal: Well, it’s fun for me, too. It’s a lot of fun, because I know that you’ve got so much to share. We’re hopefully coming to the end of the isolation caused by the pandemic, but how did you as an artist navigate this forced shutdown that COVID brought on us?

Steve Bell: Well, part of it is nice, in that the artist sort of needs that quiet and that remove to sort of dig into their soul, and try to unearth what wants to come out. So, part of it is, we get so committed to so many things, and you find yourself so busy that you’re not doing your most essential work. And so, for I think a lot of artists, besides the anxiety that comes along with that pandemic, there was something nice about, you know what? I don’t have to say “no” to anything, because there’s nothing on the table. And so, you can just sort of be quiet and you can be still and you can sit by a river forever, because there’s no work to do. And so, something about that has been really nice.

But the other part is – and you know, I’m a performance artist, so I write songs that I want to sing in front of people – and so that part has been hard, because I get a lot of energy by being in front of people. So, you do all this work of unearthing what it is you want to get out, and then there’s no one to share it with live. And so, that’s been really hard. And we’ve sort of geared up and we do all kinds of video work and we’ve learned how to be online, but that’s a one-way investment. There’s no energy coming back. You’re emoting to a camera and you’re getting zero back. So, all the energy just goes one way. And so, I’ve had to figure out: Then how do I refuel?

Karen Pascal: I found it quite fascinating, in a sense, recognizing the kind of artist you are, because you’re a storyteller and a singer-songwriter, and they meld so wonderfully together. And for example, in going into the books that I’ve been reading, like the most recent one, Wouldn’t You Love to Know, which kind of surrounds the album that you’ve created. It’s so full of your storytelling. It’s so full of your encasing what you do in a story. And you’re right, as you describe to me how you feed off an audience, audiences feed off of you, because you tell us stories. Because you position your work within a story.

Maybe take us back a bit and tell me, how did you get to be what you’re doing today? How did you get to be a singer-songwriter? Did you always know that’s where you were going?

Steve Bell: Oh, no, no. Growing up, it never occurred to me once. I mean, I played trumpet. I thought I was going to work as a trumpeter a little bit and then be a high-school band teacher. That was my goal. It never even occurred to me. I mean, I didn’t write very much music at the time; in my teen years, I might have written one or two songs. So, I didn’t even think of myself as a songwriter. I was very shy. I didn’t think of myself as a storyteller or a performer. I could imagine maybe teaching some high-school students’ band. I mean, that was about as much as it was.

Karen Pascal: Well, how did this break out in you? Because 21 albums later, my gosh!

Steve Bell: I tell too long of a story, but what happened was, I was supposed to go to Brandon University for music education as a trumpet player. In high school, they had a great music program there for education, and at the end of high school, looking back, I realized I had a bit of a nervous breakdown of some sort or some kind of an emotional collapse. And I just couldn’t go straight out of high school into university. And so, I decided to take a year off after high school, just to chill and bum around and just try to catch my breath before diving into something new.

And I ended up that winter joining a little folk trio band that played the nightclubs, and it took off. It was a little group called Elias, Schritt, and Bell. And it was kind of like a Crosby, Stills, and Nash clone band. And within a very short period of time, it was one of the most popular bands in Winnipeg. And I basically ended up never going to school like I was going to. I eventually sold my trumpet, and I bought a guitar that I liked.

And then, I started what ended up being 10 years in the nightclub scene, trying to make it in the folk/pop world. And I had a really good run at it. I was never the lead guy, and I was very shy. I would never speak on stage. So, I was always a secondary person in every band I was in, and never thought of myself as an upfront person – more of a support musician.

But I mean, there’s no money in it. And 10 years later, I’m married with kids and making no money and gone six nights a week – and in not really healthy environments. And I ended up, again, quite depressed, burnt out. And then one night, I had a very profound experience with the presence of God, in my room one night. My wife was asleep next to me, and all of a sudden, the room was filled with God – Spirit, Jesus – I’m not sure. And this voice said to me, “This time of your life is over. There’s something else I have for you to do.”

And that was the extent of it. I believed it; I believed I had been spoken to, and I thought I was being asked to put my guitar aside, that I was done. And so, I basically quit music, started looking for work. Now I’m 30. I have no employable skills. And my wife went back to teaching full-time and I stayed home with the kids. And that was the winter that all the songs that I’m known for now started happening to me.

And that’s really how I would describe it. Like, I had no vision for what I do. I couldn’t have believed for a moment that a Winnipeg folkie could make a career out of singing Christian music, or devotional. . . But not just Christian music; not the Nashville, but more the devotional, the kind of the stuff that I’m known for.

But the music started just coming and coming. Every time I picked up scriptures, I’d hear a melody. Like, it was insane. And all of a sudden, I went from writing one or two songs a decade to writing dozens of songs a year. And they more happened to me, than I made them happen.

And out of the blue, an old family friend showed up and said, “I think you should do an album.” And he pulled out his checkbook and said, “How much would it cost?” And I just pulled a number out of my hat. I said, “I don’t know, 10 grand.” And he wrote me a check for 10 grand. And that was my first album.

Karen Pascal: Oh, wow. Isn’t that lovely!

Steve Bell: Now, what happened out of that, so, that album came out, and I had no vision for that. Like, I made 200 copies just on cassettes and I hoped to sell a hundred. And then I was going to keep a hundred to give away to cousins and uncles and aunties, and, you know, people. But it started making its rounds. And I started getting calls from people saying, “Can you just come and sing at my church?” And I’d say no. I’m not a minister, I feel I’m a failed bar musician. And so, I said no for about six months, while I’m still trying to figure out what I’m supposed to do with my life, looking for work. And finally, this one pastor just would not leave me alone. And he said, “Please come sing three songs next Sunday night. You don’t have to minister. You don’t have to preach. You don’t have to do an altar call. Nothing needs to happen.” He says, “Sing three songs and walk off the stage and I’ll pay you 200 bucks.” That’s what he said. And I really needed the money.

And so, then, I showed up that Sunday night, and I was terrified. I mean, I’ve been playing bars. I’m not used to people being quiet and listening intently. You know, in the bars, you’re always looking for one or two tables that are listening to you and you play to them all night. But to have, like, 200 people staring at you? And of course, in a Mennonite church, they didn’t even clap at the end of the song. So, it’s just really awkward. But something happened to me that night, and having, like I said, never spoken between songs in the clubs, ever. But involuntarily – and I mean that literally, like it was beyond my control – I started telling stories. It was unplanned. My mouth opened and stories started coming out.

And then, after about five minutes, I’d kind of go, “Oh, I know where this is heading,” and I’d play a song, right? And then I’d open my mouth and the story would come out. And after about five minutes, I’d think, “Oh, I know where this is heading,” and I’d play a song. And it was almost like an out-of-body experience, like my own faculties were taken from me for that 45-minute set, and something happened that I never could have imagined or even hoped for. And I remember crying all the way home. I didn’t know what had really happened to me other than I knew that the God that had used my grandparents as missionaries in China and my father as a prison chaplain had used me for something that was beyond me. And that was basically the dawning of what I do now.

Karen Pascal: Isn’t that wonderful! I’m so glad you told me that story. It’s amazing, because I know you as the person that I’ve gone to so many concerts where half the joy of it isn’t just your music, it’s your storytelling, to be quite honest. It’s your contextualizing. And you know, you’re a funny guy, you’re a charming guy, but you’re deep as they come. It’s always just a rich feast, it really is. And it was interesting for me, because I haven’t done as much reading around your work as I’ve been doing over the last, I would say, week, as I was kind of preparing for today. And I was so touched by the person’s thinking behind what’s going on, and you realize God has his hand on you, Steve.

And then, I also would share with our audience, there’s a generosity in you. You have opened doors for many others. You now have a music studio and label. You’re based in Winnipeg, but I mean, you’re impacting the world, really, with the talent that you are working with. But you have always had kind of open doors for talents. I guess, you know, that person who put $10,000 down on the line to start you, my sense is you’ve started a lot of other people. You’ve welcomed a lot of people into the arena, you know, and I respect that.

Steve Bell: Well, you know what? For me, I’m not doing what I’m doing now because I saw it and went after it. Other people saw it in me, and other people said, “Not only do I see it, but here’s $10,000.” I could probably spend the whole rest of this conversation telling you those stories of people that came along and said, “I believe you can do this, this or this, and here are the resources to back it up,” whether it be money, resources or connections, or whatever. There are so many currencies out there that people have to offer.

And so, I think I learned very early, for one, that this isn’t about me, that I’m participating in something bigger than me, in something that has in, some ways, unlimited resources. So, therefore, I don’t need to hoard them. Like, I have a studio here. I don’t need to keep it to myself. I offer it – every day, there’s somebody else in there that’s using my studio. To me, it’s just an abundant cosmos and it’s an abundant life and it’s not a zero-sum game. And there’s nothing I give away that takes away anything from me. It’s just a river that flows from the throne of God. And there’s no reason to hoard it, you know? And I find that . . . it’s not virtue. This is just my experience. I find that when you are generous, it’s not like you get more stuff; it’s just that you realize it’s a river. It’s not like a superstore with limited shelf stocking.

Karen Pascal: You know, what I found that I love as well is, in the midst of what I would say is all this humility that you’re offering up right now, you’re not the least bit afraid of talent. And you bring to the stage people that you feel are much more talented than you. And I love that. I mean, it’s one of the great things that we learn, if we work in media, is we learn: Hire the best people you can find. Hire the people that will make you look better than you could possibly ever look, or be better than you could possibly ever be. You do that. You really bring forward on the stage people that just are fantastic talent.

Steve Bell: Oh, for sure. Like, even when I put together bands, I always want to make sure that I’m the weakest link in the band. And I don’t mean that in a false humility sense. I mean, the players like Mike Janzen or Gilles Fournier or, you know, Joey Landreth or Murray Pulver, or any of these people, are schooled way deeper. They’ve got way more capacity with their instruments. They’re deep, rich musicians. But what I’ve learned is it takes nothing away from me. Again, this isn’t a zero-sum game. What ends up happening is I play better. I’m elevated by their work. I become a better player. I become a more nuanced musician and communicator. And what I also find a great joy of it, is that as much as I’ve written songs that I hope delight you, I’ve got these friends that play great, and I hope they delight you, too.

And so, when you let Mike Janzen take a 32-bar solo and he just rips it up, and I’m looking out at an audience that’s never seen anybody ever play like that, and their world just got rocked. They don’t live in the same universe they lived in 20 minutes ago. And I’m so energized by those moments, symphony work, doing symphony concerts. And so many of my fans have never been to a symphony orchestra and they come out and here are 70 people on a stage. Half of them were playing, you know, $250,000 instruments. This music, in a sense, is like any one of these could do a solo concert and be brilliant, but they all submit to a common score, to a common event that’s, in some ways, beneath them, so that a greater thing can happen.

And then to me, that speaks of Trinity; that speaks of dynamic dynamism; of mutuality that belongs to the heart of God in whose image we’ve been made. And you sort of realize when you put 70 people on the stage with that kind of commitment to something beyond them, I mean, that’s gospel witness, that’s a foretaste of the kingdom, that reflects who God is, in whose image we’ve been made in. And even if you don’t, you know, drink the Kool-Aid of Christianity, you know it’s true. Something true just happened. Something deeply, deeply true – capital-T true. Not fact true, but spiritually, eternally true just happened. And you watch people swell and grow and flourish under that experience. Boy, that’s, that’s worth it for me. That’s just wonderful.

Karen Pascal: And when we talked a little while ago, and thought, “What would we look at?”, because you’ve so much good work to look at. And you had suggested, “Well, why don’t we talk a little bit about Pilgrim Year?” And I was looking at that and I thought that’s kind of interesting. It’s an amazing kind of marriage of word and music and experience.

Tell us a little bit, what was in your mind in creating – this, by the way, is a seven-book series – but just tell me about Pilgrim Year, because it’s not what I expected to find from what I thought was probably a little evangelical singer-songwriter.

Steve Bell: Right. Okay. So, this is true. I mean, I come out of what I would probably say is a fairly kindly, fundamentalist, evangelical background. Like, really good. Like my dad is a Baptist preacher. I mean, this is just the spiritual culture we grew up in. And I wouldn’t put myself in that camp anymore, but it’s the mother that birthed me and gave me my faith. And I have deep respect for it and the people that are even still in it, to some degree.

My mother had a terrible, horrible, debilitating nervous breakdown when I was about eight years old, and ended up in a mental institution for almost a year. And the mom I knew before them never came back. I lost my mom that year and this other lady came back that I adore, but it was a deep loss for me, without any ability to account for it. And all of a sudden, the pat answers out of the tradition I grew up with didn’t work. Like, you couldn’t just lob a Bible verse and make the pain go away. And I tried my best, and I couldn’t save my mom. I couldn’t heal her. God either couldn’t or didn’t or wouldn’t, you know. And at eight years old, I couldn’t figure that out, because we were good people. We don’t sin very much. We don’t smoke, you know, we don’t drink, you know, all your childish views of what it is that would make God do your bidding. Which is, in a sense, what’s happening a lot of times in those scenarios.

But I could either go one way: I could reject the God who rejected us, or I could reject the idea in total. Or I could think that maybe something else deeper is going on here. And somehow, I don’t know why, I opted for Door Number Three.

And I started paying attention to some of the richer traditions. My Dad always, as a prison chaplain, he worked a lot with the Catholic priests. I was often in Catholic worship services. And I started noticing things and I started feeling the depth of the traditions and that these weren’t a bunch of little, holy hand grenades to launch at problems. This was being steeped in a kind of truth that had nothing to do with belief or had nothing to do with facts. It was deeper than that, and I could feel it in the liturgy.

And then I started noticing in the church, the Catholic tradition, this thing called the liturgical year, that they followed a different sense of time that organized their thoughts and their lives. And it started to matter to me. And I just started paying attention, but without really much help. When I got out of high school, I found myself more drawn to Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions than the tradition I grew up in. But it wasn’t until my thirties that I actually started going to a church. It was a little, folkie Protestant church, but they did follow the church calendar year as sort of a way of organizing our faith life together, and it started to come together for me. I started to see the beauty of it, the richness of it.

So, a few years ago, I realized that for a lot of my friends, this was foreign territory. And I decided that I wanted to write a book series on the church calendar year: Advent, Christmas, Epiphany, Lent, Holy Week, Easter and ordinary time, and the beauty and the, I want to say magic, but let’s say enchantment of it. And the sort of sacramental view of time that offers you the ability to, in a sense, transcend some of the lesser questions about pain and suffering. I don’t mean to diminish them, but that they belong as something deep to something deeper.

And so, and discovering the lives of the saints and starting to feel that I keep company with Francis and Clare and with John of the Cross and with Julian of Norwich and realizing that not only is this a tradition I belong to, these are the people I’m hanging with. These are my people; they’re available to me.

And I wouldn’t want to articulate a very specific theology of that; I just sort of feel it in my bones more than anything. And I just sort of realized that I needed to somehow find language and music to pass this on to people. And so, I ended up starting to write this little series that started off just as a bunch of blogs. And then someone said to me one time, “You know, if you string a bunch of blogs together, you can call it a book.”

And I just started to realize that I had been doing this for quite a long time already. And then the right kind of people came around and said, “Yeah, we could see this happening.” And then I started actually writing this thing and I was just going to put it up sort of as an internet book. And then I got a call from Novalis, the Catholic book company. And they said, “We hear you’re doing this. Would you do it with us? Can we publish this?” And I said, “You know, I’m not a Catholic.” And they said, “Well, you’re more Catholic than most of our writers, so let’s do it.”

Karen Pascal: Well, that’s great.

Steve Bell: And they’re just such lovely people. These are not sort of high-powered business folks. These are just people that really care, love their work, and whenever they see something good, they just want to be part of it. And so, it was the easiest intro into the book world that I could ever ask for.

Karen Pascal: But there’s some sort of marriage in it, isn’t there, in terms of the music you actually . . . do you go online to sort of participate in the music? How are the two married, or is an album alongside? Tell me how you’ve put those two together.

Steve Bell: Oh, well, when I started writing the different chapters, I realized that over the years I had written songs that would go with them. And then how do you then . . .? Communicating through the written word is different than communicating through the sung word. You know, there’s things you can sing-say that you can’t say-say. Like music itself is a language that is not translatable to English or German or French or Italian. It’s its own language that doesn’t have direct equivalents in other languages. Like, you see this when scholars write and they want to quote — they’re English writers, but they want to quote a German-speaking person. And they say, “You can’t translate this. You have to know the language.”

And music is kind of like that. Music knows things that no other language can articulate or know. And I realized that a long time ago. And so, I thought, “How do we put the music with the written word here to sort of just deepen the experience?” And so, we put out CDs that would go along with the books, but of course, nobody’s buying CDs anymore. So, we just put them all up on a website. So, as you read the book, at the end of a chapter there’ll be a link to a song I wrote, or someone else wrote, and you can go to the website and you can listen to it and reflect.

Karen Pascal: Well, I love hearing the journey of how you’ve become a contemplative, because that’s kind of evident. And this morning it was funny, because this was the daily meditation from Henri Nouwen, about the contemplative life. And it said: “The contemplative looks not so much around things, but through them, into their center. Through their center, he discovers the world of spiritual beauty that is more real, has more density, more mass, more energy and greater intensity than the physical matter. In effect, the beauty of the physical matter is a reflection of its inner content.”

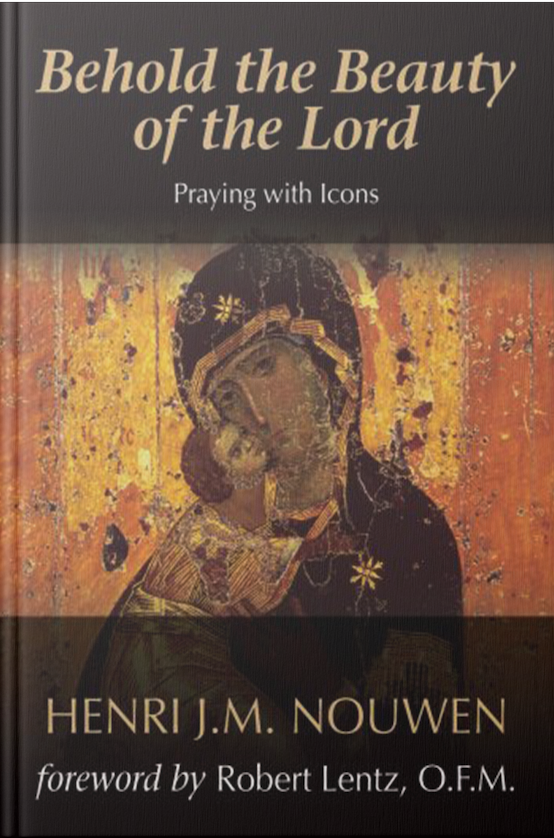

Steve Bell: Well, see, perfect! And this was a conversion experience of sorts for me, was reading Nouwen’s Behold the Beauty of the Lord. And I remember, I tried to get into his more prose-y things, and I’m kind of pretty ADD, and I have a hard time with the “long quiet,” and all those sorts of things, but having that visual, having those icons, and then reading his reflections, and him sort of curating those icons and helping me see through them to what they were looking at that – these were glasses. They weren’t to be gazed upon as the end point. They were the doorway to something richer, deeper, truer, more alive.

And it was in reading that book that I first started to glimmer: What if all of creation is that way? Like, what if every tree, every bug, every star, every human, every rock has at some level that capacity to be seen through? Well, that changed my world. And then I read his Prodigal Son, and how he sat in front of that painting for days, and the things that he saw through that. I was gobsmacked. Like, could a human being like me learn how to see like that?

And so, he’s full of words like “behold,” right? I mean, that’s a key word, behold. And then you realize as you’re beholding, you’re also being held. And that this isn’t a one-way street; this goes both ways. And all of a sudden, you realize, “Oh my goodness, this changes every moment of every day. It changes how I look at everybody, at everything, how I interpret every experience.”

It’s all sacred. It’s all pointing outward and inward at the same time. And it’s all mystery, but it’s all knowable, just not necessarily specifically limited to the English language or my set of metaphors, right? So then, I can imagine an eternity of learning new metaphors so I can understand deeper. I can foresee that that would never end. You would never come to the end of the riches that are available, as we continue to look and learn how to see, then how to articulate, using the many languages that we’ve been given, whether that’s body language, or musical language, or linguistic language, dance language, film language, whatever. And also, you realize, oh, I could hang around for eternity for this. I could see the goodness of that, right?

Karen Pascal: That’s an amazing image, and an amazing understanding that you’re bringing to it. I want to talk about this latest album, Wouldn’t You Love to Know, and I need to describe it for our listeners. It’s not just an album; it’s this incredible book. It’s so exquisite. It’s beautifully crafted. And it just, in a sense, I think it parallels what we were just talking about, this sense of seeing beauty and seeing through things, and knowing. I’ve been so touched by it. It slowed me in my tracks, just to kind of read, word by word, your description of each song, where it’s come from, where it’s going, and then just little moments within it that just took my breath away, to be quite honest.

I’m going to start here, right at the beginning. You say, and this is about your own faith, and you’ve talked a bit about this, and I love this quote: “I didn’t become a baptized follower of Jesus at the tender age of nine because Christianity made sense in my head. Indeed, I still find it somewhat bewildering. But something about the story stirred deeply in the dark fecundity of my soul’s longing, like a moistened, buried seed, responding to the warmth of the sun it cannot see or imagine. I haven’t come to love God because of what I know, but rather I’ve come to know God because of what I’ve loved.”

You caught me with that right at the beginning. And of course, you use one of the favorite Nouwen words: fecundity. I didn’t know what fecundity meant until I discovered it from Henri. He was always talking about fecundity, fruitfulness, you know? That was a new word for me.

Steve Bell: Well, you know, you get that from soil, right? Like rich, deep soil. It’s needed for fecundity. It’s nutrient-rich, right, and it holds moisture and it’s a beautiful word. It’s a very beautiful word to use. What happens is that, in our rational or post-rational mindset in modernity, we just haven’t been able to imagine the depths of the Christian faith outside of this cold, calculus sort of way of thinking about it. So, you know, we’ll kill each other over doctrines. We’ll kill each other, we’ll destroy each other over different moral commitments or whatever, as if somehow, that’s the secret or the essence of our faith.

But if we started thinking, “fecund” or, the other great analogy, too, is the womb, that we’ve been “enwombed.” I find it really interesting when Jesus is talking to Nicodemus, he says, “You must be born again.” Well, that’s a maternal image, that’s not a male, patriarchal image. If anybody wants to have a discussion, does God embody or transcend the feminine, but the key line is “you must be born again,” that you must be re-wombed. And there’s just something about the darkness and the mystery of what happens in a womb, and the deep connectedness between the child and the mother, and the shared nutrients, and all that kind of stuff, and a child is being prepared for a world it can’t imagine, that it finds bracing and cold and frightening at first.

And then the child is also equipped to do that for someone else. To bring life to someone else. You start to really reach into those metaphors, and suddenly – not that theology is not worth our time. It is worth our time. Not that doctrines don’t matter – of course they matter. But these aren’t essential things. There’s something far richer, far deeper, far more beautiful, far more mysterious happening there. In my faith, I think what I’m trying to get at with what you read there is that – I grew up being very mindful of this womb-like safety and beauty and warmth and love and security and moistness. I felt the goodness of God in a way that I couldn’t articulate.

And then when someone started telling me basically, well, the face of God is Jesus. And I started looking at those stories of Jesus. And I went, “I recognize this. This resonates with how I have always known God, since sort of almost pre-language.” I looked no further at that point; I didn’t need to. It wasn’t that I became a Christian over against other faiths. I just stopped looking. I know this resonates, and it doesn’t even resonate in a way that obliterates other worldviews, but just one, again, that can enwomb all of them, and bring them to their deepest selves. And somehow, I got that.

Karen Pascal: In this lovely album, one of the songs is In Praise of Decay, and you struggled to deal with your father’s pain. And I was so touched by the encouragement he gave to you. He encouraged you to make peace with your powerlessness. And I thought that was profound.

Steve Bell: Yeah, Dad was that guy. He had a thousand lines like that. And the story behind that line was when, in his dying days, he’s suffering bitterly with real pain and indignities. And I remember coming to his room one night and he’s asleep. And as he’s sleeping, his body is shuddering with pain. And I’m weeping over my father (and I’m going to start now). And he wakes up and he sees his son struggling, you know? And I just said, “Dad.” It’s just like, he was a really good man. He was, legitimately, a very good man. And I said, “You deserve better than this. You have lived so well, if anybody deserves a glorious exit, it’s you.” And I said, “This isn’t right. It’s not fair.”

That’s what came out of me. And that’s when he looked at me and said, “Steve.” And then he said – I wish you could hear his tone of voice, because it’s with a smile – he says, “Go away and make your peace with powerlessness. It’ll go much better for you.”

And then he said, “I’m not scandalized by suffering.” And there’s a pause. And then he said, “The most beautiful things have happened to me in this bed. People kiss me that have never kissed me. People say tender things that have never said tender things. People touch me that have never touched me. People share things they wouldn’t have otherwise. Everything I wanted most in my life is happening around this bed of suffering.”

And then he said with a wink, “Who wouldn’t wish this on their best friend?” And he wasn’t making light of pain, but you can hear his deep faith in all of that. And it wasn’t just, if you just squint your eyes, you can get through this to the glory. It was the glory.

Karen Pascal: Wow.

Steve Bell: Right. This isn’t the passageway to beauty or to salvation or to glory. This is it. In the same way that Henri Nouwen doesn’t . . . Like Ronald Rolheiser said about Henri Nouwen’s writing one time. He says that the unique genius about Henri Nouwen is he doesn’t write about spirituality. His writing is his spirituality. It is the thing it’s pointing towards, and Dad saw suffering and glory in the same sort of way.

Karen Pascal: It’s interesting, because when you use the word “scandalized,” it’s a word that I actually associated with Henri. He was not scandalized by the pain or scandalized by the issues of sin. He just wasn’t scandalized by it. But that is the most beautiful description. And it’s funny, because I’d have to say, this beautiful little book to me pivots in a way around In Memoriam, which is a song that you wrote for your father after he died, in memory. And the other day, I had just read it and I was dealing with a friend who was going through such, was actually recognizing that pain. Grief had trapped her almost for a lifetime. And I read your very, very honest assessment about grief, that was so beautifully written. I don’t know if you want to, if you have it before you, I would suggest you read it to us. If not, I’ve got it here. But as you begin that, In Memoriam, “My father died.” If you started there, it was so wonderful how you captured the truth of this.

Steve Bell: Okay. So, this is how I begin this chapter. For listeners, basically, with my last album, basically to summarize, I wrote a book to go with the album. So, there’s a chapter for every song. So, this is the opening of the song I wrote for my dad called In Memoriam:

My father died of cancer last summer, July 26th, 2019. Approaching his death, I thought I knew what grief was and certainly expected it to be a rough ride. But it turns out I had no idea. Grief over the death of a beloved one isn’t merely a deeper level of sadness or loss than, say, the loss of a treasured belonging. It’s a different thing altogether. It’s a cellular thing. It floods and colors every molecule of your being and significantly alters your perception of everything else. Nothing is the same. Nothing will ever be the same, and neither do you want it to be. A return to sameness would be a denial of the beloved’s significance. Even now, almost a year later, grief is ever-present, like a low hum of a highway in the distance.

Karen Pascal: I just found your genuine understanding and sharing of that so very helpful, so very real. You can’t push aside grief. It is its own; it colors life in its own way. And I felt that was wonderfully helpful to my friend, I can tell you. The song is beautiful. The story of how that song came is amazing. Do you mind sharing that? It’s quite interesting. I was delighted as I read it.

Steve Bell: Well, a few months after Dad died – and of course, when Dad died, and anybody that knows me knows how profound he was in my life and how hard it was. But you know, around a funeral you’re dealing with other people’s grief. You’ve got all the details. And so, you don’t really get a chance to have your own thing. And so, after a couple months, I said to Nancy, my wife, I had to travel to Alberta to do some . . . I had some medical issues that needed looking at with my wrist, a specialist there. And I said, “Is it okay if I just take a couple of extra days and just go grieve my dad?” She said, “Of course.” And so, I booked a little hotel and I’m out there for a few days and lots happened when I was out there just being quiet. I’d just drive into the Rocky Mountains and I’d sit by a river and cry, you know?

But on the last night, I came back and I was heading home the next day. And I went and got some supper and I got a bottle of wine. And I’m sitting out in my hotel balcony, I’m sort of sipping on this wine, watching the sun go down over the Rocky Mountains, and the first line of that song came. And I was thinking about how around my dad’s bed, I got to know some of his friends, I got re-acquainted with some of my relatives that I hadn’t seen for a long time. Like, a lot of things happened around a dying person’s deathbed that are lovely, you know? And so, this line came to me: “Fresh tenderness is burgeoned with the dying of my dad / And I love him all the more for it.” And I just realized, I was just grateful for all these connections that had happened around my dad’s deathbed in his dying days.

And so, I sat there with that line and I was thinking, well, that’s a line, you know, that could start a song. And about half an hour later, another line came, and then half an hour later, another line came. And over a period of a couple of hours, I would just pick up my phone and sort of just write into Notes, so I wouldn’t forget. I don’t even have my guitar there, so it’s not like I can sort of see how this is going to work melodically. Within a few hours and a bottle of wine, this whole song comes out that I wasn’t trying to write.

And by about midnight it was done. I realized I had a song here that I wasn’t even trying to write, and I should save this to something. And I think I copied it and I wanted to send it to myself in an email. And I erased it by accident. The whole song was gone. And it’s midnight, I’m exhausted emotionally, physically. I’ve got the better part of a bottle of wine in me, so I’m not exactly sharp, right? And I realize that if I don’t now try to remember the song, I’ll never get it back the next day. And I ended up till four o’clock in the morning, just remembering this word and that word and going, “Well, that was the end of the line, so what would that have rhymed with?”

And I had to rebuild the whole song just to remember it. And I did. It took hours, and I finally got the song back. And what I love about that is that the song came as a total gift. Like, it came unbidden, but I end up having to, and privileged by having to, fight for it at the same time. And that to me was lovely as well: that it came as a gift, but then I had to fight for it. And so, somehow in my bizarre imagination, that’s significant, you know, so it’s kind of a fun story.

Karen Pascal: I like the story. And the part of me that’s lived in the world of being a creative person got it. It met me in an interesting sort of way. And I can remember struggles and how important it is to work, to get what’s being given to you. Not everything that just floats into your head is a line that works. But I love the fact that you worked to keep something that was such a gift given to you.

Steve Bell: Yeah. Like it was no work, and it was the most work I’ve ever put into a song in my life, in an eight-hour period. Like, it was just the stupidest thing, but there’s something poetically true and beautiful about that as well. So, I mean, all of life is gift, you know, but it’s all work, all the time. And so, it’s both. So, to me, I don’t know if it was a learning moment or deepening moment for me, but it made the song more meaningful as well.

Karen Pascal: You know, you wrote in this little book that goes around, Wouldn’t You Love to Know, you wrote, “Whenever we find ourselves mesmerized by the work of a great artist or a great soul, we talk of being spellbound.” Steve, I’m spellbound by the artistry and the wisdom that I find in the writings of Steve Bell, and in this conversation. Steve, it’s just a gift to be with you. It really is. And the thoughtful freshness, and realness of what you give us is wonderful.

I want people to discover Steve Bell. Yes, he’s a great conversationalist. It’s fun to talk with Steve Bell, but please go to his website (we’ll give you all the links) and discover his music and his creativity, and you will be the richer for it. I’m going to entrust the secrets of those who are listening to the safe hands of Steve Bell. Take a spiritual journey with him, let him sing to you from the heart of God and the words and the ideas that are fresh and are genuine. He speaks very truthfully. His creations are going to draw you to the deep center that we talked about in terms of contemplation of the deep center. That is where God dwells. Thank you for being with us today.

Steve Bell: Oh, thank you.

Karen Pascal: Thank you for listening to today’s podcast. What an honor for me to spend time with Steve Bell. For more resources related to today’s conversation, click on the links on the podcast page of our website. You’ll find links to anything Steve and I talked about today, as well as book suggestions. If you enjoyed today’s podcast, we would be so grateful if you would take time to give us a review or a thumbs-up and pass it on to your friends and your companions on the faith journey.

Thanks for listening. Until next time.

Praise from our podcast listeners

Sign Up for Our FREE Daily Meditations & Newsletter!

Help share Nouwen’s spiritual vision

When you give to the Henri Nouwen Society, you join us in offering inspiration, comfort, and hope to people around the world. Thank you for your generosity and partnership!