-

Robert A. Jonas "My Friendship with Henri" | Episode Transcript

Karen Pascal: Hello, I’m Karen Pascal. I’m the Executive Director of the Henri Nouwen Society. Welcome to a new episode of Henri Nouwen: Now and Then. Our goal at the Nouwen Society is to extend the rich, spiritual legacy of Henri to audiences around the world. Each week we endeavor to bring you a new interview with someone who’s been influenced by the writings of Henri or perhaps even a recording of Henri himself. We invite you to share the daily meditations and these podcasts with your friends and family. Through them we can continue to reach our spiritually thirsty world with Henri’s writings, his encouragement and of course his reminder that each of us is a beloved child of God.

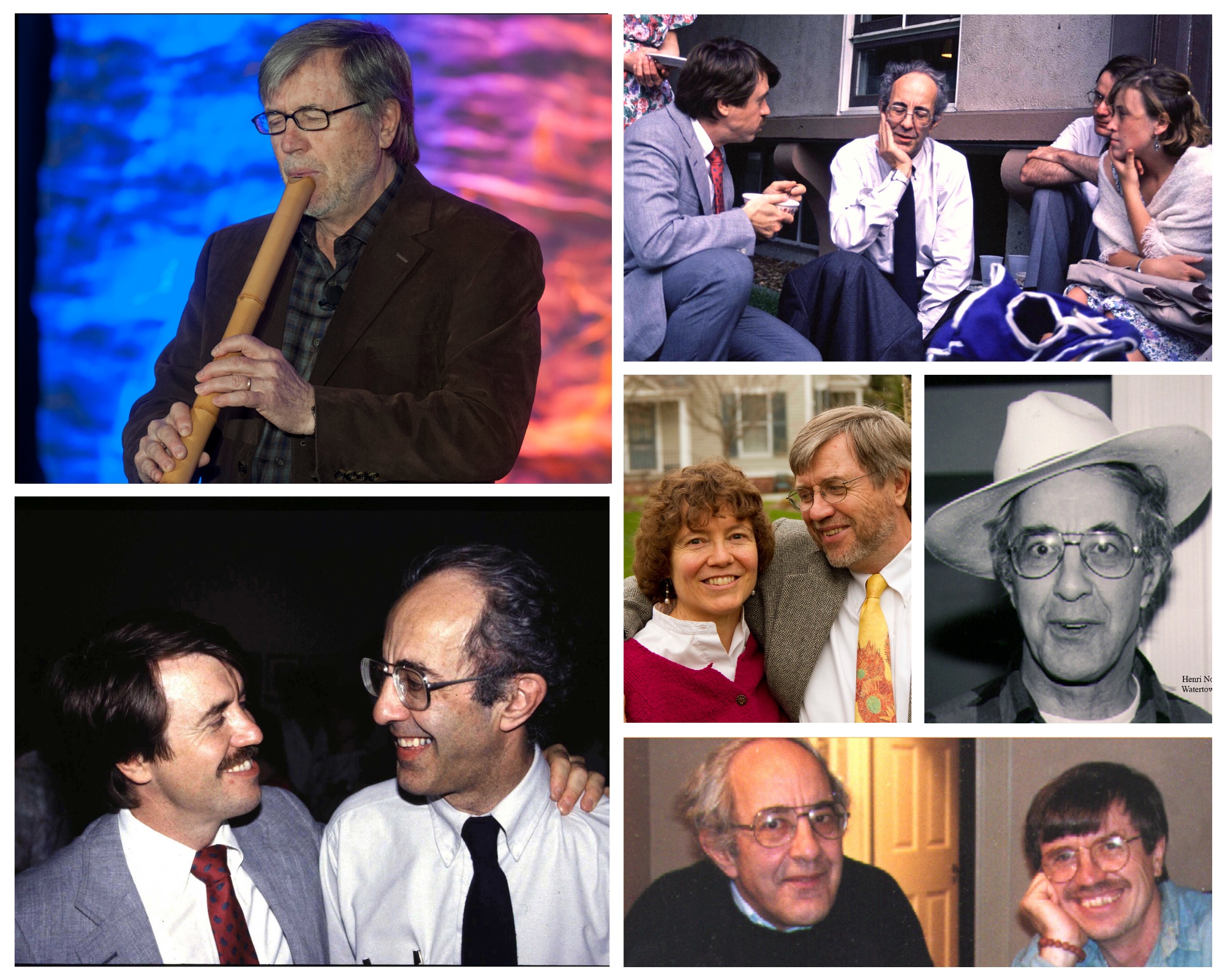

My guest today is Robert Jonas. He’s best known as Jonas, by the way. He was a good friend of Henri’s and author of three books. He is a psychotherapist. He’s also somebody who leads spiritual retreats, he does land conservation work, he writes articles and he has a unique way of bringing together a deep understanding of Buddhism and Christianity. That’s been part of his life work. I want you to meet Robert. He’s a good friend and someone who I cherish the way he knew Henri because he helped me know Henri through his friendship.

Oh, Jonas, I’m delighted have a chance to chat with you because we’ve known each other for many years. You were a person who, in essence, helped me discover who Henri Nouwen was. I came to visit you when I was doing a documentary on him. And you were a friend and you were somebody whose book had actually been most helpful to me at the time. You had written a book called Henri Nouwen Writings: Selected with an Introduction by Robert A. Jonas. And I had loved your introduction. I found it to be the one that actually guided me through the documentary. There was kind of the essence of Henri there and you really understood him so I wanted to meet you in person. And then I recall coming to you in Boston and that was kind of the beginning of our friendship. Tell me just a little bit about that friendship that you had with Henri Nouwen.

Robert Jonas: I met Henri –and the year starts to dissolve in my mind–but I think it was 1982 or ’83. I was in graduate school getting a doctorate in psychology at Harvard and I heard about Henri through some friends who said, “Oh, you must hear this guy he’s over at Harvard Divinity School giving talks.” So at that time I had just been through the final stages of a painful divorce and met Margaret who was also a graduate student. And she was doing her dissertation in comparative literature, in Russian literature. So we went together with Margaret’s mother who was a Buddhist teacher. So we sat in the front row at St. Paul’s church in Harvard Square, and Henri was giving a talk. And there with us was another Buddhist teacher. So there were the four of us who were wavering between staying Christian or becoming Buddhist. And so it was a critical moment for me. And Henri got up, there were 300 people or so, and he started talking about Jesus in a most unusual way. He was dressed like a Harvard professor, not a Roman Catholic priest. And he was able to weave together Christian experience and a little bit of Zen and a little bit of loving Jesus in a way that felt a little bit for me, like Oral Roberts from the 1950s or Billy Graham, but more sophisticated, more cosmopolitan. And I immediately said, “Wow this is incredible. I gotta meet this guy.” And I should mention that was unusual because I was being trained in psychoanalytic psychology and reading Freud that religion was a projection from our childhood experience of our parents and all that.

So it was quite an astonishing experience for me. So I went up to him after he talked, I was the first person in line. There was a long line and I said, “Wow, this is incredible. Can we have lunch?” And Henri’s response immediately was, “Well, I don’t know, but let’s have…” “Oh, I said, would you be my spiritual director?” It was even more brazen. And he said, “Well, I don’t know, but let’s have lunch.” So we had lunch in Harvard Square, and then we became friends for the rest of his life.

Karen: Oh, that is so cool. Now I know I’m catching you at a moment where you are a retired psychotherapist, you lead spiritual retreats, you do land conservation work, but clearly Henri had a very formative part of that spiritual life in you. So tell me a little bit more about that friendship and how you influenced each other.

Jonas: Yeah, sure. So I was just in clinical training at Harvard. And then I was, I think at that time in 1983, ’84, I was beginning an internship at Wrentham State school, working with handicapped people. And that was going to be my clinical internship for my doctorate to become a licensed clinical psychologist. And so Henri was just beginning to be interested in L’Arche. He had visited in Trosley in France, the basic L’Arche community, the foundational community. And so our conversations included talk about psychology, spirituality, handicapped people, marginalized people. We had a lot of common views of reality, and we both had a devotional life. But the thing is we were kind of, I don’t know how to describe it, we were trying to figure out who we were to each other. We knew we liked each other immediately, but I started asking Henri questions about his parents. What was his relationship with his father? What was his relationship with his mother? And of course, this is part of my psychoanalytic training. Where did Jesus come in there? How did he integrate his early childhood experience with him meeting Jesus? And that interested me for my own life, because I grew up in an alcoholic home in Northern Wisconsin. My parents ran a bar and I witnessed domestic violence, my parents fighting, beating each other up, my mother having missing teeth and black eye. But at the same time my grandparents introduced me to Jesus in the Lutheran church. So I had these two experiences of trauma and that Jesus was an eternal presence and Henri understood that.

But we didn’t quite know how to do this or what this was; what our friendship was all about. So for a while, he, for several sessions, asked me to be his therapist and we tried that out. And he actually paid me and I thought, wow, this is wonderful, Henri’s so famous and I’m his spiritual director. You know, I was immature and it was kind of an ego thing for me. But I soon discovered that wasn’t working because he didn’t take any of my suggestions and he was not a good listener. And I got frustrated and I think he got frustrated too. So we decided, well, that doesn’t work. So we split apart for a while, I don’t know, six months or a year. And then we came back together and had lunch again and decided, why don’t we call this friendship? Why don’t we be friends? So at that point, he was no longer my spiritual director and I was no longer his therapist. So we had started out with a kind of professional mindset that we had to be professional with each other, and that gradually dissolved. And then I visited him at Trosley. And then when he left Harvard, I was part of that sendoff committee, not physically present when he left Cambridge, but we called each other. He talked to me about leaving for Toronto from Cambridge. And then we, you know, over the years we just met, probably once a year. I went to Trosley, I mean I went to Toronto, stayed in the retreat center there. And then he visited us occasionally when he came to Cambridge.

Karen: What was it like having Henri as a friend? Was he difficult? I mean I didn’t always hear everybody saying he was the easiest person to be a friend with. I mean there was lots of issues. And tell me a little bit about that.

Jonas: Yeah. I agree with all that’s been said in that direction, that’s true. He could be so incredibly present and listening and I really needed his basic message that he repeated in so many different ways, that we are the beloved. And what is said of Jesus is said of you so that the experience Jesus had of feeling the presence of the Holy Spirit and realizing that the very core of his life was God’s belovedness in him, that I can have that experience. So that it was a very different from my Lutheran upbringing where Jesus is sort of a beloved historical figure, but in the past, and we can sort of call on him, but Henri’s message was, “No, he’s rooted in your life right now, moment to moment.” So that was an incredible message. And he could listen to me in my devotional life with great depth and understanding and guidance, and he could listen to me talk about the psychodynamic aspects of both of our lives.

For example, he could share with me things like he would visit his father and they would go to a B&B in the Schwartz Valda every year, I think, or most years, but Henri said, “When I would go into my father’s bedroom, I would see all my published books in the corner stacked and unread.” So I knew there was some pain there that he really never talked about very much. So we had that kind of very personal sharing. But on the other hand, he could be very demanding in terms of his attention, he could be quite narcissistic and at any moment it would be all about him. And so just one example that he talks about in the Sabbatical Journey book. I was going to visit him in Trosley and this would be 1985 or early ’86, I think and we made a plan that I would come and visit him and he’d be staying in Trosley in France. But I was just going through a very dramatic change in my life, deciding whether I want to be married again or not, and married Margaret. And so kind of at the last minute, instead of going to see him in September, I told him in August that I couldn’t come because Margaret and I were going to get married and how wonderful that was and so and so forth. He was not as excited as I thought he would be. He was actually upset that I was not going to come and visit him. And I learned later that therefore he stopped calling me for a while and he was very hurt that I did not come to visit him, even though obviously it was extremely important for me in my life and life changing to become married. So I didn’t learn that he was actually upset as much as he was until I read his book Sabbatical Journey where he mentions how upset he was. So I was kind of surprised to read about that in a book later.

Karen: It’s a funny thing. As I got to know Henri through his friends and his family, his colleagues, I discovered this incredible longing for friendship and intimacy and friendship and commitment to him, which I thought was really, he captured in some ways what we all feel. We long for people to make us in a sense, give us back our worth. And his understanding of that actually is that which ultimately gives us tremendous revelation of how he needed to put God in that place. Henri’s life journey is just so life-giving because he’s incredibly honest with his neediness and we see ourselves sometimes there, I mean we just can’t help but see it.

Jonas: Yeah, that’s right. It’s so funny too, because one of his central messages to people is that God loves us unconditionally, no conditions whatsoever. But when we expect unconditional love from others, from people, we will always be disappointed. And he said we’ll get glimpse of unconditional love that are real and important, but we won’t get the full Monty, if you will. That can only come from God. But at the same time, he couldn’t quite live that message.

Karen: Now you’ve written a couple of books that are about Henri. You did Essential Henri Nouwen with Shambala Press. And there’s a lovely quote in this: “We always have a choice to live the moment as a cause of resentment or a cause for joy.” That’s Henri Nouwen’s quote. And it strikes me as an incredible line as we look at where we are today with the pandemic. “We always have a choice to live the moment as a cause of resentment or as a cause for joy”. How are you doing with the pandemic, you and Margaret right now? What’s happening in your lives? And what from Henri have you been able to draw that’s a value?

Jonas: Yeah, thank you. He’s changed me so dramatically that I almost can’t separate myself from Henri, from his presence and his message. So in that way it’s a difficult question. For example, after I wrote the first book about Henri in, I think, 1996 with Orbis Press, I got so into his world. I really wanted to take in that message that he brought to us and then I started leading retreats based on Henri Nouwen all over the country really. And at a certain point, it happened that I had to separate from him. I didn’t know, I had to find my own spiritual life. So I stopped leading retreats on him for a while and I was on the Henri Nouwen Board. I did that, but I felt that my exploration was more interspiritual than Henri’s. I had a foot in the Buddhist world doing Buddhist meditation. So what’s happening now is Henri supported me to start the Empty Bell Retreat Center in Watertown, Cambridge area in Massachusetts in 1994. I started doing retreats, contemplative Christian retreats that were friendly to Buddhism back then in 1994. Then we moved. In 2004 I built another Empty Bell in Western Massachusetts in North Hampton. And three years ago, we moved to a different part of North Hampton. I built another Empty Bell. It looks like a Zen retreat center. It’s attached to our house.

And now, during the pandemic, I am leading Zoom meditation retreats on Sunday mornings. And these have been incredibly helpful for me. So I host about 12 or 15 people in each group. Sunday mornings are Christians who have gone east to Buddhism and Hinduism and want to come back and integrate these things. Tuesday evenings are just people in our community and our neighbors. That’s very interspiritual, so they’re Jews and Buddhists and Christians in UU and UCC and all kinds of folks. And then on Wednesday morning, is anybody here in what’s called the Pioneer Valley. So the meeting with people by zoom has been incredibly rewarding and just looking at people’s faces on the zoom screens– I just learned to love them really. And in all these groups we’re getting to that place where we just feel each other’s presence so keenly that we can say, I love you to each other and really live that life of love together. Even across disciplines, even for the Buddhist in the group who don’t use the word. They don’t use the word love very much, Buddhist tend to use the word compassion. But what I always say to them is that Jesus was not afraid to say, “I love you, or do you love me?” I’m not sure that Buddha ever asked, “Do you love me?” Buddhism is a different kind of spirituality, but what it does do that I haven’t found very much in Christian life and in teachers is when you talk about making a choice between regret and what was the other word you used, resentment, or a cause for joy. Okay. Cause for joy. So what I learned from the Buddhist is that it really is moment to moment, like right now, as you and I are talking together, I feel an openness in my heart to what is happening right now. Not you the Karen I used to know, or the Jonas that I used to know or want to know or pretend I am or any of that. It’s what is actually happening in the moment, the openness to raw experience. That’s something I got from Buddhism that I never was taught by any of my Christian teachers. It was more, my Christian life was more moral and hopeful and very, you know, positive and love. But what was lacking about it for me is the fierceness of facing into reality just as it is.

Karen: That’s powerful.

Jonas: So that’s what I’m doing, trying to do, right now in this pandemic and helping others do that too.

Karen: I think that’s going to be very valuable to our audience right now, to be quite honest with you. Everybody has different ways of handling what’s going on but it’s obviously this amazing life –changing, path-changing moment for all of us. So finding the way through it and living in the moment is quite important I think. I got a treat just a couple of weeks ago on the celebration of the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, actually on the Sunday before that. At the National Cathedral in Washington your lovely wife, Margaret Bullitt-Jonas was the speaker and it was beautiful. I really enjoyed it. Tell me a little bit about the journey the two of you have had, because in essence you have really gotten involved in doing some important work right now that deals with the environment; that deals with creation. I’d love to hear a bit about that.

Jonas: Yeah, sure. Thanks. So Margaret and I are both involved in environmental stuff, her from a more Christian spiritual angle that God creates creation to be loved just as we are created to be loved and to love each other. So she puts creation right in the center of the liturgies and even changing here and there some language of the creeds, whatever it takes to get nature and creation more in the center of our spiritual lives. And I’m doing the same thing. One more practical path I’ve taken is I have been a Board chair of a land trust here in Western Massachusetts. And so we actually do the financial and economic and legal work to set aside tracts of land so that nothing can ever be built on those tracts of land.

Here in west Massachusetts about 1200 acres a year are set aside legally in perpetuity so that they can never be developed. And those are places where now at the Kestrel Land Trust website, for example, we have about 12 maps of areas to hike around here, where you can take an hour, two hour hike through the woods, through the wetlands and the mountains. And it’s extremely satisfying work. But I have to add that when you do environmental work there’s been a great split between environmental work and spirituality over the last couple centuries. And it goes back to Christians being opposed to evolution and things and science. So now Margaret and I are both part of conversations trying to say that science is a beautiful, creative, brilliant creation of the human mind, the human heart.

And so one can be deeply spiritual and be a scientist at the same time. So climate change is real, evolution is real, reality is real if you will. And we can have a deep, inspiring radiant Christian life simultaneously. These two – it’s not two. There’s this saying in mystical Christianity, not two, not one, it’s both. There’s a oneness in our lives with creation and each other. And also differentiation is beautiful. Seeing things as they actually are separate from us. So right now I’ve been working on a book on Holy Trinity for many, many years, and it’s getting close now. And what I’m doing there is saying that the Trinity, the model of three and one is actually the dynamics of our awareness, our awareness with each other, and our awareness in nature.

So that’s taking a lot of my time right now, and I hope to finish this year.

So Margaret and I are always having these great discussions. One last thing I want to add about my relationship with this, when I met Margaret, we were both graduate students and facing our dissertations, which, you know, was a terrible experience and we had arranged for a dinner at her house. And so I was driving toward her house and I had this old rickety Dodge Dart, and it stopped operating about a mile from her house. So she had to come and pick me up. And so her first thought was, oh, who is this guy he can’t even afford a car. And we get into her house which she owned at that time. She was fortunate. And she burned the fish that she was cooking for me and I’m thinking, oh my God, she can’t cook. And then we started talking and the first things we talked about, we bypassed our doubts. We started talking about God and about life and death. And I started to cry. I had not experienced such an openness of love. And she said, “Well, what’s wrong?” And I said, “Nothing’s wrong. I’m happy.” And that was our love experience right away in 1982. And then when we got married, Henri said at our reception, “There’s so much love in these two people separately there’s going to be a lot more love for the world when they get together, when they get married.” That was a beautiful thing for him to share.

Karen: What a lovely prediction that was, my goodness. So he’s really been part of your life even through this transition, obviously. I love hearing that love stor. That really moves my heart. The other thing that I enjoy so much about you, Jonas, is you’re so creative. I mean you don’t put boundaries around, “I’m just a psychotherapist”, or “I’m just a writer” and you’ve written some wonderful books, but you have this enjoyment of nature, this enjoyment of beauty, this enjoyment of music. Tell us a little bit about that. Let’s start with the music, you play an instrument and you play it wonderfully. And in fact, you have three albums out, I believe. Tell us a bit about what you play and what you gain from that experience.

Jonas: Yeah, thanks. I was a psychotherapist in doing organizational development in the eighties after I finished my dissertation and after I worked at Wrentham State School. And a lot of my clients in psychotherapy had spiritual lives. And I began to realize more and more that that’s where I wanted my focus to be not so much on psychotherapy, but what do we find when we see through the boundaries of the ego? We find divinity, we find the divine and I wanted to explore that. So I talked with Henri a lot about it and he encouraged me to get a post-doc Masters. So I went to Western Jesuit School of Theology in Cambridge and got a Masters to integrate Buddhism, Christianity and psychotherapy. And my thesis was on those three.

I think I called it a perfect storm of healing, psychotherapy, Buddhism, and Christianity. And while I was in a seminar on Thomas Merton the teaching fellow stood up and played a bamboo flute that he had learned to make and to play in Japan. He was getting a doctorate on Buddhist Christian dialogue at Harvard at the Divinity school. And I heard this instrument blowing through the bamboo, and I realized, this is my instrument. I have to learn how to play this. So I started taking lessons with him, and then he introduced me to Yoshio Kurahashi his teacher in Kyoto. I started bringing Yoshio Cambridge to the Empty Bell and the Empty Bell became the place to learn this instrument for anybody living in the Boston area. And the instrument’s called a Shakuhachi. And if anybody’s interested in hearing this, if you go to iTunes, one of my albums is on iTunes. It’s called Blowing Bamboo, and you just type in Blowing Bamboo and you’ll see several different albums, but the one you’re looking for is Robert A. Jonas. So when Buddhist monks played that instrument for many centuries their spiritual practice was to become Buddha in one sound. So when I played it as a Christian and play it now, it is to become Christ in one sound, like St. Paul saying, “Now not I, but Christ in me.” It means letting go of my ego self, my self-referencing thoughts, who I think I am, who I want to be, who I would prefer to be. Letting go of all those ideas of who I am and letting the clarity and a kind of emptiness, the kenosis of Christ come through every note. So that’s what I do when I lead retreats I always play the Shakuhachi. So anyway, I’m just trying to integrate my Christian life. My whole life in is about Christ in the best way I can. And so I integrate writing and video and music and friendship and community building or community co-creating – this might be a better way to say it.

Karen: Wow. I’m so glad to introduce audiences to you, Jonas. You have been a friend, an inspiration and I really love the fact that you knew Henri so well that you were a friend and at the same time, probably somebody who could be very, very honest with him where he needed honesty. But you have a rich tradition that you bring. When people go to the show notes for this particular podcast, I want to list the books you’ve written, and I’m sure there’s going to be people who would like to get in on that zoom not so much counseling, but really the way you’re ministering to people right now, where they are in the midst of this sense of everything’s changing and it is frightening for people. It is uncertain times and many are facing losses and just need somebody to come alongside of them and be with them through that. And we’re so grateful. Almost on a daily basis we hear from people who say, “what Henri’s saying to us right now, or what Henri’s saying into my life right now is exactly what I need. And it brings a calm to me.” And I’m grateful that we can share Henri right across the world. It’s exciting.

Jonas: I have to say about zoom that what’s best is anybody who would like to join a zoom community that I’m hosting, that it’s really essentially the Christian contemplative tradition. It’s the moment to moment experience that is informed by Buddhism, but it’s always been there back to the early centuries after Christ. So many people now have to sequester and be alone and we’re not used to it, but look at all the beautiful saints that have chosen solitude. They knew how to handle it whether they were living in urban settings or in the desert. Robert Ellsberg now has a series out. I think it’s on YouTube, but also through his Orbis Books website where he’s reviewing a lot of Christian saints who have lived in isolation on purpose and pointing out how we can learn from them.

Karen: I’ve loved his book, All Saints. It’s one of my favorites. I just really enjoyed it. In fact, he has a Saint for every single day and some aren’t people that you would think you’d call saints, but Robert has a very beautiful, broad view of that. And it has really been a treat to pick that book up and go to the day and study a life. And actually, I think it’d be a great thing to use right now.

I’m glad to hear you say that it’s about the contemplative Christianity, because that’s very significant right now, people are looking for it in the midst of being alone. It’s another step to find peace in that aloneness and to connect with God in a deeper way. So I’m delighted to hear that that’s what’s happening right now in terms of how you are zoom meeting with people and that’s lovely.

Jonas: Yes. Thank you. And by the way, I just have to say that you are the best interviewer that I’ve ever experienced. Thank you.

Karen: That’s so kind of you to say. It’s always fun to interview a friend because you want to just go to the corners of their lives and things that you have been inspired by and things you want to bring out. And it’s really been a delight to talk with you. And I think in the midst of it what is really important, and perhaps you might want to have a last word on this, is we are in a time like no other for all the world, a time, like no other. But what is the best you can offer into people’s lives right now that you know will be life giving?

Jonas: Well, I thank you. I don’t know. I’m discovering myself, I’m discovering the importance of friends and family in a way that I hadn’t experienced before. And the preciousness of life, of each moment that this doesn’t have to be so, but it is. And Henri sometimes used that phrase actually. So when I am able to walk outside, oh my God, a tree, a cloud, a flower that enjoying the preciousness, the contingency that this doesn’t have to be so, but it is. It’s such a wonderful experience. And I know, also to work with things like even living with Margaret. We totally love each other after 35 years of marriage, but we’re watching very closely now, like never before, where we get irritated with each other and where we get annoyed or angry or any experience where the openness and acceptance and inner peace begins to be affected. To inquire right into that moment and either talk to each other, or just say frankly, I need some time alone. So yesterday, for example, I just went out. I spent the whole day somewhere else. It just became apparent that there was a little irritation in the air. So I disappeared. And when I came back, it was wonderful to re-emerge in the family.

Karen: I bet there’s a lot of people that are going to take that little piece of advice. The reality is you’re forced into being together far more than you’re used to. And in the midst of that, finding the ways to undo the moments that are really irritating or annoying or frustrating.

Jonas: And I would say don’t feel bad or reject negative feelings like irritation, annoyance, fear, anger. Explore them. This is what the contemplative life is all about: is that inside the fear is a love greater than you ever imagined. Inside the irritation there’s– I use this metaphor in your documentary about sitting at the edge of the Grand Canyon–the vastness of God’s love is available. That is bigger, more vast, than any particular feeling we’re having in the moment, feelings are not the end story. The end story is the vastness of God’s boundless love.

Karen: That’s beautiful. Robert. That is just beautiful. Thank you. Thank you, Jonas. I will thank you as the name that I should call you. Thank you for this.

Jonas: No, that’s great. That’s great. I love it. Thank you, Karen.

Karen: Oh, you’re so welcome. And folks, as you’re listening we thank you for being with us for this, and there’s lots of things that we’ve mentioned during this talk and you’ll find them in our notes on the website. So please take time to go there. It will lead you to books. It will lead you to videos. It will lead you to YouTube videos, and we’ll be sure and connect you with Robert Jonas. We really want to be a resource to you. Thank you for listening today until next time.

In the words of our podcast listeners

Sign Up for Our FREE Daily Meditations & Newsletter!

Help share Nouwen’s spiritual vision

When you give to the Henri Nouwen Society, you join us in offering inspiration, comfort, and hope to people around the world. Thank you for your generosity and partnership!