-

Henri Nouwen "The Prodigal Story of Forgiveness" | Episode Transcript

Karen Pascal: Hello, I’m Karen Pascal. I’m the executive director of the Henri Nouwen Society. Welcome to a new episode of Henri Nouwen, Now and Then. Our goal at the Henri Nouwen Society is to extend the rich, spiritual legacy of Henri Nouwen to audiences all around the world. We invite you to share this podcast and our free daily meditations with your friends and family. Through them, we can continue to introduce new audiences to the writings and the teachings of Henri Nouwen.

Welcome to our first podcast in our spring lineup. We always love to give you the opportunity to listen to Henri Nouwen himself. This Nouwen talk that we are sharing with you today, was given in 1995 in Portland, Oregon. It’s about forgiveness. Henri, in his own very entertaining and disarmingly honest way, tells the story of the return of the prodigal son. And in the telling of it, he reveals with great honesty so many of the struggles he has had in his own life.

Here is Father Henri Nouwen telling a deep story of our shared human struggle that links us all to the gospel story of the prodigal son and his broken relationship with his father.

Henri Nouwen: If you think about forgiveness, which text do you most obviously think about in the New Testament? For me, the story, the text that is most directly speaking about it is the story of the prodigal son. So, I’m going to read it to you and just ask you to listen to it in a very meditative way, to really enter the story and look with your eyes, your inner eyes, your inner ears, listen with your inner ears to that story.

“There was a man,” Jesus said, “who had two sons. The younger one said to his father, ‘Father, let me have the share of the estate that will come to me.’ So, the father divided the property between them. A few days later, the younger son got together everything he had and left for a distant country, where he squandered his money on a life of debauchery. When he had spent it all, that country experienced a severe famine, and now he began to feel the pinch. So, he hired himself out to one of the local inhabitants, who put him on his farm to feed the pigs. And he would willingly have filled himself with the husks the pigs were eating, but no one would let him have them. And then he came to his senses and said, ‘How many of my father’s hired men have all the food they want and more, and here am I dying of hunger? I will leave this place and go to my father and say, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you. I no longer deserve to be called your son. Treat me as one of your hired men.’

“So, he left the place and went back to his father. While he was still a long way off, his father saw him and was moved with pity. He ran to him, clasped him in his arms and kissed him. And then his son said, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you. I no longer deserve to be called to your son.’

“But the father said to his servant, ‘Quick, bring out the best robe and put it on him. Put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet. Bring the calf we have been fattening and kill it. We will celebrate by having a feast, because this son of mine was dead and has come back to life. He was lost and is found.’ And he began to celebrate.

“Now, the eldest son was out in the fields, and on his way back as he drew near home, he could hear music and dancing. Calling one of the servants, he asked what was it all about. The servant told him, ‘Your brother has come, and your father has killed a calf we have been fattening, because he has got him back safe and sound.’

“He was angry then, and refused to go in. And his father came out and began to urge him to come in, but he retorted to his father, ‘All these years, I’ve slaved for you and never once disobeyed any orders of yours. Yet, you never offered me so much as a kid for me to celebrate with my friends. For this son of yours, when he comes back after swallowing up your property, he and his loose women, you kill the calf we had been fattening.’

“The father said, ‘My son, you are with me always, and all I have is yours. But it is only right that we should celebrate and rejoice, because your brother here was dead and has come to life. He was lost and is found.’”

The topic, the subject is forgiveness. And it’s a really, really tough subject. Forgiveness is one word for love, in our life together. You know, love, you can speak about generosity or kindness or friendliness or gentleness or . . . Love has many, many words, but one of the most important words, I think, for love, as we live love here and now, is forgiveness.

And so, this morning, in starting to talk about forgiveness, I realize that it’s a much harder subject than I often claim it to be. Because even though I say, “Sure, I should be a forgiving person,” it doesn’t take me more than a few seconds to realize that I’m not there yet.

And that I can say I’m giving this long talk about forgiveness, but right as I talk about forgiveness, there is somebody that sits there in the corner of my soul that I’m not very happy about, and not ready to forgive or to be forgiven by. So, it’s something that on the one hand sounds extremely important, and we can agree with how important forgiveness is. On the other hand, it doesn’t take very much to realize that to be a person in whom forgiveness has been incarnated, that’s a huge, lifelong journey.

Now, I would like to talk about two subjects: about receiving forgiveness or asking for forgiveness or receiving forgiveness, and about giving forgiveness, offering forgiveness. I think it’s very important to make a distinction between the two. Quite often, we think, oh, we should forgive our neighbor. We should forgive our friends. We should forgive this person who has hurt us. But for me, the question is not only just are we willing to forgive, but are we willing to be forgiven. Are we willing to ask for forgiveness and to receive forgiveness that comes to us? And I’m absolutely convinced that giving forgiveness is easier than receiving, and that in many ways, to offer forgiveness to others and to say to others, “you are forgiven,” can only be possible if we experience ourselves as forgiven persons, as being forgiven, as people who have been able to receive forgiveness. And in that sense, you cannot give what you have not received. You cannot give forgiveness if you in no way have experienced what it means to receive it, understand? So, there are two important things.

And this morning, I would just like to talk exclusively about receiving forgiveness, not about giving – we’ll talk about that tomorrow. And the story of the prodigal son is a good story to work with, because it’s a story about three people, basically: two sons and a father. And very quickly, I just want you to think two daughters and a mother. It’s about relationships.

And so, this morning we’d like to talk about these two sons, the two daughters, these two people, and explore a little bit with you how these people look like. And for you, it’s really important. You know, it’s not a story. It’s about you; it’s about me; it’s about us. So, and later on in your meditation or in your discussion, it’s not a question about analyzing that story, as discovering your own. So, where are you? So, think a little bit about the older, the younger son. Think about that for a little bit. Think about you as the younger daughter, you as the younger son. And if I think about it, I feel really, really sympathetic with this person, really, with this guy. He had such a model father, who knew all, everything so well and who had it all together, and so on. And quite often, my father knew it before I even wanted to know it, or my father gave me answers before I even had a question. My father was telling me what is good for me and what’s good for you and how you should behave. And what’s so wonderful when I know what life is all about. “I’ll tell you, son, you know, what’s good for you and how to do it.”

Finally, I just want to say I got oppressed here. It doesn’t feel free for me. I want to discover my life on my own. I want to find out what’s good and what is bad and what is sinful and what is not sinful. I want to discover if life is interesting or not interesting. I don’t want just you to tell me exactly how I should live and what I should do and tell me what is wrong or what is right; I just want to find it out for myself. You know, give me a break. Give me a break. I want to get out of this nice family, where everybody knows things so well, where everybody is so organized and planned. And so holy and so, so damned good.

I want to get out of it. Don’t you have this desire to just be a pagan, to do everything that you’re not supposed to do? Don’t you have the desire to just do all the things that everybody else says are sinful and shouldn’t be done? You don’t even have a chance to try them out. People even before you’re born are telling you what to do or not to do. You have a rebel in you, that you have to think, “Gosh, maybe that whole Christian story is lot of nonsense. I just want to go and do it myself. And I want to play around and go out of this safe place and go to a foreign country and be a stranger. Nobody has all these ideas about me that I come from just a good family. So, so decently behaved. I just want to be unknown. I just want to run around and do things and find out what life is about.”

I think it’s a total healthy desire, you know; I had it and still have it. Sin boldly! You want to sin boldly, you know, to really do all the wrong things, just to find out how it feels.

I’ll just talk about this [inaudible]. You have to get in touch with that place in you, really. You have to see if that’s there somewhere. Maybe it’s not even in you, but if it is, don’t be afraid to, you know, live. You come from a church – not everybody, I think, but I don’t know who, but if you are from the Catholic church, then you certainly come from a community where it seems that everything is already decided before you even have a chance to make your own judgments. Often people live it that way, feel it that way. It just becomes oppressive. It becomes a straitjacket. I want to break out. Give me my money! Give me my share. I’ll go and do it myself. Thank you for your education. Thank you for letting me do all this. But I finally want to get out of here and find out life by myself, and not just giving me all these little lectures. This is what the [inaudible] supposed to do. And this is what is good behavior. What, a good guy looks like. And this is what a good girl looks like. And I just can’t stand anymore. I just want to get away.

And there’s a lot of lust there, lust, you know, good lust. Good lust, good energy, good erotic energy. Good, good desire to, to be sort of. . . You know, we are people with a body and we are full of energy and vitality, and where can I let it go?

So, it’s very interesting. I want to be free. I want to discover for myself what it means to have a body and to be a life. I want to test out my own life.

So, what happens when you or I finally end up with the pigs, what are we going to do when we end up in dissipation? Okay. Because this is what happened with him. Dissipation, money, lost women, stranger. Nobody talked to him anymore. He was totally lost. And in a way he chooses to be lost. He chooses to be lost. He was lost in dissipation. He tried it all out. And finally, he had nothing anymore. He lost his name and his popularity and his money and his innocence and his purity. And he was just lost. And it’s interesting, you know, there are quite a few people who finally choose to be lost. It’s better to be lost than to be oppressed. It’s better to lose it all on my own than to be part of this authoritarian family that tells me what to do. I mean, there are people who finally choose that it is better to lose. You have to be in touch with that yourself. That is a part of you, of me at least, that raises that question constantly.

You feel it, but it means when you are lost and you hear your dad say, “I always told you so. If you would do that, you would end up with this. I wanted you to stay home. I always told you so; it wouldn’t work. See?” Now you sit there and you hear your dad saying that, while you’ve lost, and you say, “Damm this, dad. I prefer to be lost than go back to that boss. I finally prefer to be lost than to be back home with him. At least I got rid of him. Now, I might get rid of everything else, too, but at least I don’t… know what I mean? So, returning home can never mean going back to the old paths and finally saying you were right. I’m sorry. You’re so right, I shouldn’t have left.

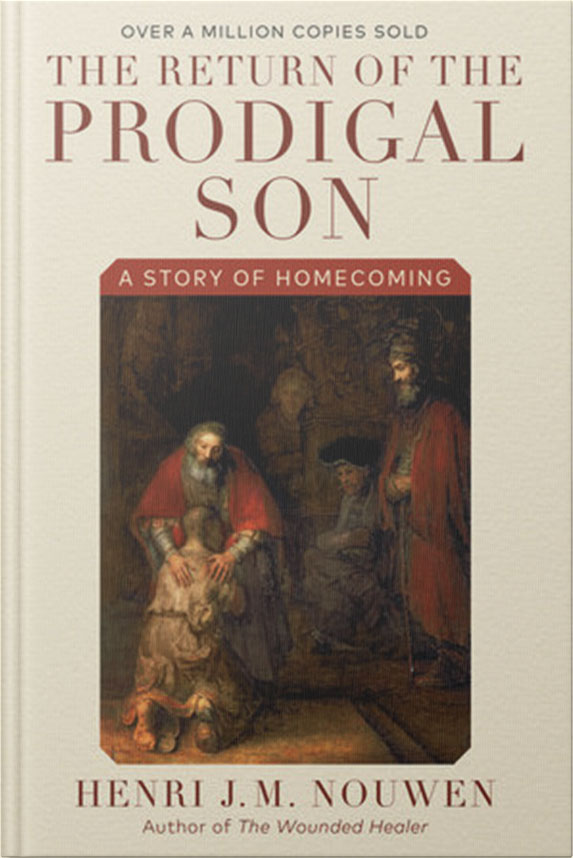

And you know, what is interesting about this whole thing is, when Rembrandt painted the prodigal son, he painted him with a dagger. He had lost everything, but he still had a dagger, a little dagger here. And the dagger is a sign of sonship. It’s a sign that I am the son of my father. And I’m still the heir, I’m still the successor of my family. I’m still in line to take over from my father somewhere. I belong to that family.

Rembrandt painted that dagger as the dagger that made him return. That when he had lost everything and he just had to make a choice, whether to self-destruct, commit suicide, or really dissipate completely, or to return, that he suddenly in some very deep way realized that he was the son. That he belonged to his father and to his family. And that beyond all the judgments about being authoritarian or oppressive for this or that or such and so – all these things – there was something deeper. There was a connectedness, there was a belonging that was still there. And yet yes, yes. Maybe my father was right, but I’m not going to return because my father was right. I’m not going to return simply because I want to go back to the old place. I want to return because I haven’t forgotten who I am, finally. I am the son; I am the daughter. I am a member of the family. I’m part of that community. I am the beloved of my father, even when my father wasn’t able too well to express it to me or show it to me or make me feel so good.

And that’s still who I am. And instead of choosing to let myself be totally lost, I choose to return in the knowledge of who I am. And I want you to realize something very important for me: Just realize that the return can never mean to just go back to the old situation. It means something very different. It means that, as I rediscover sonship, it doesn’t mean just being the obedient little boy who does what my dad says. It means something else. I don’t know yet what it means, but I have to reclaim my daughterhood, my sonship, my belonging in a different place.

And as I reclaim that, I have to also reclaim fatherhood and motherhood in a different way, to redefine that. It cannot be just that the old boy and the old dad are getting back together. Somehow sonship and fatherhood are being redefined emotionally as this return takes place. And that’s, when we talk about forgiveness, that’s where we start to receive it, to ask for it. Somewhere, it requires a new way of thinking about who we are and who the one is of whom we ask it.

To receive, to say, “Father, forgive me,” somehow has to come from a place in us that helps us discover who we are, but helps us also discover who the one is of whom we are asking forgiveness. To receive forgiveness, to enter into a question of forgiveness, is a way of rediscovering who we are.

Secondly, think about yourself. Turn it all around. Forget about the younger son for a moment. Just think about the older one. And you know, the older son, is anybody here an older son? If you are the older son, you will be even more sympathetic to the story. The older son stayed home. He stayed home and he wanted to be the obedient one, the hard-working man who was going to do what his father asked him to do. He was staying home. He worked hard in his father’s farm. He looks for duty.

Now, that’s very much who I am in many levels. I mean, somebody once said to me, “You always think you’re the youngest son, but I think you really are the older one.” You stayed home most of your life. Home means you did what was expected of you, what your father wanted, or your mother wanted, or your schoolteachers wanted, or your church wanted. You’re always trying to do your best. And you got high points and high degrees. And somewhere, you did it. You fulfilled the expectations of your bosses. And you were nice – always sort of nodding to people who seemed to be a little more important than you were. But you weren’t close to them. In fact, you worked hard to please, to please, to please, but as you try to please your dad or your bishop, or your friend or your boss, whoever it is, your teacher, as you please, you are looking for intimacy, for affection, for friendship, for a community, and you didn’t get it.

And at some point, in your heart, you are jealous of your younger brother, who had the guts to go and do his own thing. But you couldn’t do it: “I’m supposed to keep the honor going here.” Somewhere, the older son is mad, angry, jealous, too, of his younger brother who left, because although he stayed, he didn’t even feel the freedom in himself to go. He felt sort of constrained by his duty. He has to keep up the right image. He has to represent the family. He has to be “my oldest son,” look well-dressed. Nice guy, does exactly what his father, mother expect. Always has his tie on when he comes to the education, he’s doing the right thing. But interiorly, interiorly, that’s a lost person, too. In a way, interiorly, the oldest son is as much lost as the younger son, because he’s physically at the same place, but emotionally he’s as alienated from his father as the younger son is.

I had a friend who lived like the younger son. Did anything that I didn’t dare to do, but he did it. And then when he was about 25, he became a Catholic. He had done all the things that I was dreaming about, that he was doing them. But then he got converted and he became a Catholic, was baptized in church and he met me and he says, “Henri,” he says, “I think you really should pray more.”

I said, “I should pray more. I should pray more. You, who have done everything you’re pleased to do, are going to tell me, who has been obedient in church since I was four years old, not anything but the holy father told me. And you’re going to tell me that I should pray more? Who do you think you are?”

You know the anger? The anger that comes sometimes from people who are home, but not home, who are in the church, but not in the church? Who are a part of the religious community, but really are sort of angry about the fact that they never are out of it? The church is filled with resentful people who sort of don’t leave it, but stay in it resentfully, angrily. And resentment means cold anger. You’re angry, angry, angry. And finally, it’s not hot anger anymore. It’s just sitting there. You don’t even know how resentful you are. And you have to think about yourself, where you are the oldest daughter or the oldest son, and where you’re angry. It can be at your father or your mother. It can be at your church, or it can be at a teacher. It can be at a person. It can be somewhere else. But, one of the hardest things for us is to claim our resentment.

Where we are not free. Resentment stifles us, gives us a hard, cold heart, a hardened heart that we live with it so long, we don’t even know how resentful we are. Life is full of resentful people. Also with lustful people, but also with resentful people. You know, people angry at somebody. And really it comes down to is that they haven’t ever got over that hurt or they feel, I’m here, but maybe I shouldn’t be here. I’m here, or maybe that’s maybe I hadn’t the courage to be anywhere else, or whatever.

Every community has that. The church has it, L’Arche has it. People wherever, particularly the Christian community, because the Christian community makes such an enormous moral claim on us that quite often, we obey. But we don’t obey while being really free in it. We remain resentful. Somehow, we feel that somebody else is telling us to stay at home and we do it and we do it and we do it and we work and we say, “Wow, you know, here’s your younger son, he’s coming back and you’re giving him your calf, you have a big party. And I am here, always here. I’ve done exactly what the holy mother church said. I did exactly what my teacher said. I did exactly what my dad said. I did exactly what the holy father says. Exactly, right? And you don’t even get me a thank-you note. I don’t even get any friendly words from any bishop or pope. You know, I’ve written about 30 books, and a bishop never said, “Thank you, Henri, for these wonderful books.” All the Protestants say that, but not the Catholics. Nobody. I only get honors from those Protestants.

And my own people don’t even love me! And they don’t even say anything nice to me. They ask me things to do when they don’t know how to do it themselves. But that’s all. And I know, if I say one thing wrong, the holy father will be [sending] a letter. Or the Bishop or the nuncio. So, whoever, you know? My father always said to me, “Henri, I’m only going to read your books when the Vatican has forbidden to read them, because only then do you say something interesting.”

So, it was just a joke, but it was basically saying, you know, you’re so obedient, you’re so nice. You always say the right thing that everybody likes to hear, but you don’t have the guts to say something that they don’t like, because they’re going to tell you, and you’re going to say, “Oh, poor me. Why don’t you love me more?” Resentment. That’s resentment, you know? That’s all around us. It’s all around us. It’s there. And I want to tell you, it’s a lostness. It’s a lostness. And returning from resentment is a lot harder than returning from dissipation, because you don’t even know you are resentful. You know, if you’re in with prostitutes and throw all your money away and gamble, well, that’s pretty obvious what you have to return from. But when you just resent that you’re at home or you do all the right things, you don’t even know that you have something to return to.

And how to receive forgiveness as a resentful person? That’s just a very, very good question, because we often don’t even think we need forgiveness. We’re self-righteous. We said we do the right thing. The problem is my brother, not with me. How to even return? In the story of the prodigal son, whether this brother, all of a sudden, returns, we don’t even know. That story doesn’t give us the answer. It doesn’t say, “And then he finally joined his brother at the party.” No. There’s no words about the end of the story. And Jesus told the story to the Pharisees to be self-righteous people. The whole story is about, in that sense, about the elder son. It’s not about the younger son, it’s about the elder son, who sort of did the obligation, but basically wasn’t able to really listen.

And what, again, I want to say to you is as the older son in you looks for healing, for asking and receiving forgiveness, it’s basically a conversion of yourself as the older son and a conversion of the father and the mother and the power figures, also. When I ask forgiveness for my resentment in the church, then I have to have a very different interior understanding of what obedience is all about, and what it means to be a member of a community of faith. Whether there is a Pope or a bishop or leaders or whether it’s ministers or whatever, you know.

I mean, asking forgiveness again doesn’t simply mean, you know, I want it; somehow, you have to really reshape your own understanding of yourself in the community, and it requires a whole new understanding of fatherhood and motherhood and childhood. So, if you now have some sense of who you are as the older or the younger son, older or younger daughter, now the question is how to return and receive healing and forgiveness.

And to claim your dependency means to become like a child. Not to stay like a child, to become like a child. Jesus says, if you don’t become like children, you cannot enter in the kingdom. Jesus doesn’t say, stay like a child. It’s not the dependency of a baby. It’s the dependency of a mature person who says, “When you were young, you girded yourself and when, where you wanted to go. But when you grow old, you’ll stretch out your hand and somebody else will gird you and lead you where you rather wouldn’t go.”

That is a spiritual dependency, spiritual maturity. They call that the “second childhood” or some people call it “second naivete,” a second openness. It’s not a dependency out of which the younger son left. It’s a new dependency. It’s a dependency of chosen and freedom. The dependency of the child that is open to receive, and you and I have to claim it, claim, in that sense, our dagger and say, “I’m your son, I’m your child. But I want to be it, and I’m not ashamed of it. And it doesn’t mean I’m going to just crawl on the floor for you. And I’m standing in front of you. I’m your child. I’m the heir. I’m willing to be the heir. I’m willing to be the child. I’m willing to be the child of my father, whether it’s my heavenly father or my earthly father, I want to be who I am. I want to claim my childhood. And as I grow older, I want to claim it even more, because I become dependent again, physically, but more emotionally and spiritually. I discover my deepest vulnerability.”

And only when you claim that dependency, you can receive forgiveness. Ask for it, because you have to say, “I need you. I need your forgiveness. I need your healing.”

I had a car accident a few years ago, and the doctor said I was going to die, because of interior bleeding. And, right at that moment, I had this incredible grace that I discovered that I was God’s beloved child. And it was a grace that I never had before. And I’d done a lot of things in my life I regretted, and done a lot of things I wish I hadn’t done. And you know, I’m basically a scrupulous kind of person, not always very moralistic and coming out of a very highly moral tradition. And somehow, I felt maybe I’m not ready to die. I have to earn heaven first, you know, live a little longer. But when I was dying, suddenly I had this sense of God was saying, “Henri, what are you so scared of? I love you. I’ve always loved you. And here you are.”

And it was an enormous sense. And one of the most amazing things of that experience was that I was able to receive forgiveness just because I was willing to be a child.

Secondly, it’s the willingness to be interdependent. In the story of the prodigal son, it’s very interesting that the two brothers don’t want to be brothers, you know?

“That son of yours who squandered his money and went out with loose women. Why do you treat him?”

And the father says, “Your brother has come home. Come and have dinner with us.”

But the older son doesn’t even acknowledge his younger brother as brother. He acknowledges him as “that son of yours,” not “my brother.” And one of the most important things is that we are willing to be interdependent, that the younger brother and the older brother want to sit around the same table. You’re my brother, you’re my sister. You’re different. You do things that I wouldn’t have done. And I do things that you wouldn’t have done. But we are both children of the same father. And therefore, we can be together as brothers and sisters. Different cultures, different races, different languages, different styles of life, different customs, but somehow, in a very deep way, we belong together. And you and I have to really learn and think [inaudible] very much about it is to explore the joy of being brothers and sisters.

We live in a society where we try to prove constantly that we are not like others. I’m better than you, faster than you, smarter than you. I compare myself always with people. I do that interiorly all the time. How do I compare with him or with her? How do I make up in the competition of life? A lot of competitions, interior competitions, you know, it’s not always running in the athletics or in school, but it’s also interiorly. Did he think he’s a better or I am a better person? And we constantly are busy with comparing ourselves with others and wondering how we fit and what people think about us and how they feel about us. And sometimes our joy then gets connected with where we do special things that others don’t do, special rewards or special compliments or special this. And Jesus is calling us to a joy of being brothers and sisters: You’re like me. And that’s so nice about it. You and I are so much the same, you and I belong to the same family.

I don’t know if you ever had that little experience that you’re from where? From Quebec? And imagine somebody comes up to you and says, “Hi, I am John.”

And you say, “Oh, I’m Judith. And where are you from?”

“Well, I’m from Quebec.” You are also from Quebec. Wow, you know?

“And where do you live at?”

“I used to live right around the Citadel there.”

“Well, I do, too! And I’m always buying my vegetables there.”

And do you know why it’s exciting? You know, we are all the same. You know, you get very excited about discovering you’re from the same village. Or he’s from Holland, too. You know? Another boy from Holland at the same seminar. Isn’t it exciting? It’s joy, you know. It makes it joyful. Not because he’s different, though. You have so much joy because he’s just from the same place. Huh?

Now I want you to experience that as to be, “Wow, you are from the same humanity as I am! Same eyes, two eyes, two ears, just like me. Born like me, struggling like me, going to die like me. Wonderful. Just the same. And that’s so joyful. Isn’t that wonderful? You and I belong to the same humanity, same planet, same creation. Isn’t that joyful, to be brothers and sisters?

And receiving forgiveness has a lot to do with that. If you can claim that, if you can claim that sameness as a source of joy, you can forgive each other a lot easier, because you basically say, well, you know, we’re around on this world for a few years and we struggle, but what we have in common is really what is the source of our joy: We have in common our human flesh. We have in common our mortality. We have in common our being born. We have in common that.

And so, we better sit around one table and eat from the same bread and drink from the same wine and have the same words of thanks. That’s what the Eucharist is all about. The brothers and sisters coming around the table and saying, “We are children of God.” We can forgive each other. This is the lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world. Forgive, forgive. He came to make us a community of forgiveness, and it can only be that if we claim or accept the invitation of the Father to come in and be part of the same party.

And thirdly – and this is something that is finally a very practical question – stepping over your wounds. This is so hard for me to do that, to step over my brokenness. That means, for me, that if I am hurt by you, I am willing, at some place in me, to let your hurting me not define me. Know what I mean? To let your hurting me, not saying who I am. But if you hurt me deeply, I’m going to be the hurt one for a long time. You know what I mean? She offended me. He hurt me. The church rejected me. The society put me in the corner. Whatever. And I am the rejected one. And if you talk to me, I’ll tell you how they treated me. And I will remind you what my mother did or what my church did or what my father did. And I have something to tell you that people who [inaudible] there. You want to know who I am. I’m Henri Nouwen, and my bishop just did. . . Or I’m Henri Nouwen, and this publisher just did. . . Or I’m Henri Nouwen and L’Arche just did to me. . . I’m Henri Nouwen. Let me talk to you about all these things that happened to me. And I have something to say, and I won’t forget it, because if I forget it, who am I? Because I’m the rejected one.

And the world is filled with people with a negative identity. That’s what a negative identity is. I am the rejected one, the abandoned one, the hurt one, the wounded one. And I’m not trying to say that these wounds aren’t real and that these wounds aren’t really very painful. And that these wounds aren’t really very unjust and that you’re not treated unjustly, sometimes. I’m not trying to romanticize and sort of forgive and forget it. I’m trying to say, if you are being hurt and wounded and rejected, which you are – no human being isn’t rejected somewhere or abandoned. And we live with people whose life is very much marked by rejections.

That’s what L’Arche is about. But what we want to say is that we do not allow the world to identify these people by their rejection. They’re not just rejected from the beautiful people. They’re good people. They’re loving people. And I want to say that to them, myself.

I tell you, this is one of the hardest things to do. I had an experience of severe depression, about four years after I got to L’Arche. And I felt deeply rejected by a person, and so much so that I had to leave Daybreak, because I just was so depressed. I just felt, so this person really cared for me and opened up very deep places in me.

And finally, that person says, “I cannot be with you any longer, Henri. I don’t want to see you anymore.” And it was so painful, because precisely the person who had loved me best had rejected me most. And that was not because he was a bad person, but it was simply because that person couldn’t hold onto me.

But the way I lived it was like, “I’m the rejected one.” And as soon as I identified myself with the rejection, I couldn’t do anything anymore. I couldn’t minister in the community. I couldn’t be a priest in the community. I couldn’t do anything. I was totally paralyzed. The whole day and night I keep screaming. I keep inside the agony, that I was the rejected one. I was the abandoned one.

And I didn’t know how to step over that and believe that that’s not true, because the rejection of the other became self-rejection. And I started to eat it up in such a way that I felt a no-good person, the rejected one. And one of the great struggles to receive forgiveness, and to ask for it, is to step over that negative identity and, somewhere, find in yourself a place where you know that that person who rejected you, for whatever reason, isn’t telling you who you are. That you are God’s beloved child. You are a brother or sister of all people. And if you claim that, you can step over that wound and claim the truth.

And that can take years. And I’m not saying it’s a little heroic act. It might take healing. It might take therapy. It might take friendship. It might take affection. It might take a lot of touch. It might be a lot of massages. All the things. But finally, somehow you have to start believing that you are more than your wounds, although the wounds are real and painful. And that’s the way.

So, these three things, through your dependency, your interdependencies, and stepping over the wounds are the ways.

So let me just conclude here. This is really the end, now. Finally, I want to say, as you go into your groups, the question that you are left with in terms of forgiveness is, from where do you live? The younger son could have chosen to live from the place of his dissipation, and that would’ve killed him, finally. The older son could have chosen to keep living from the place of resentment, and that would have alienated him completely.

But it is a choice, a choice to live, to choose to live from the place where you are free, the place beyond dissipation and resentment, the place where you claim being the heir, where you claim being the son, the daughter. Where you claim the truth that the father to whom you return is your father, your mother who became flesh. And it’s like you and Jesus – all of that where you finally choose, choose to live.

You can make that choice about every minute of the day. I tell you, when I wake up in the morning, I think about people. I know some of them, I think about with resentment. Can I keep choosing to step beyond that? And the other side of resentment is gratitude. And the other side of dissipation is a certain loving containment. So, as you think about all that in terms of forgiveness, do you choose to live towards forgiveness, to ask for forgiveness, to receive it, and to believe that you finally are a forgiven person? And even beyond your resentment and beyond your dissipation, there is forgiveness. There is healing. And that you are, as the beloved child of God, as the brother and sister of humanity, you are forgiven. You are forgiven.

That’s what Jesus keeps saying: “You are forgiven. And not because you did that. Or you had a little speech, or because you had this nice little gesture, you know, you are forgiven. That’s what I come to say. It’s a free gift that I offer you. And can you please receive it?” So, you can receive the truth of yourself and live in this world as a forgiven person who has received forgiveness. And that’s a choice. That’s a real choice. It doesn’t happen automatically. You have to choose to be forgiven. You have to be willing to say, “Yes, I want to be forgiven. Yes. I want to be,” and say, “Come into my heart and give me a new heart. Give me a new spirit. Give me a new life.”

“I will give you a new heart, not a heart of stone, but a heart of flesh. I’ll give you a new spirit, a spirit of joy and peace and forgiveness.”

That’s the Spirit. The spiritual life is the life of the person who has claimed to be forgiven and therefore carries around the divine life into the world.

Karen Pascal: Thank you for listening to today’s podcast. Wasn’t Henri wonderfully honest? He challenges us to return to the Father and choose to be dependent. And then he opens us up to also choose to be interdependent, to form community.

For more resources related to today’s podcast, click on the links on the podcast page of our website. You’ll find links to anything mentioned today, as well as book suggestions. If you enjoyed today’s podcast, we’d be so grateful if you would take time to give us a review or a thumbs-up. Please pass this on to your friends and family.

Thanks for listening. Until next time.

Praise from our podcast listeners

Sign Up for Our FREE Daily Meditations & Newsletter!

Help share Nouwen’s spiritual vision

When you give to the Henri Nouwen Society, you join us in offering inspiration, comfort, and hope to people around the world. Thank you for your generosity and partnership!